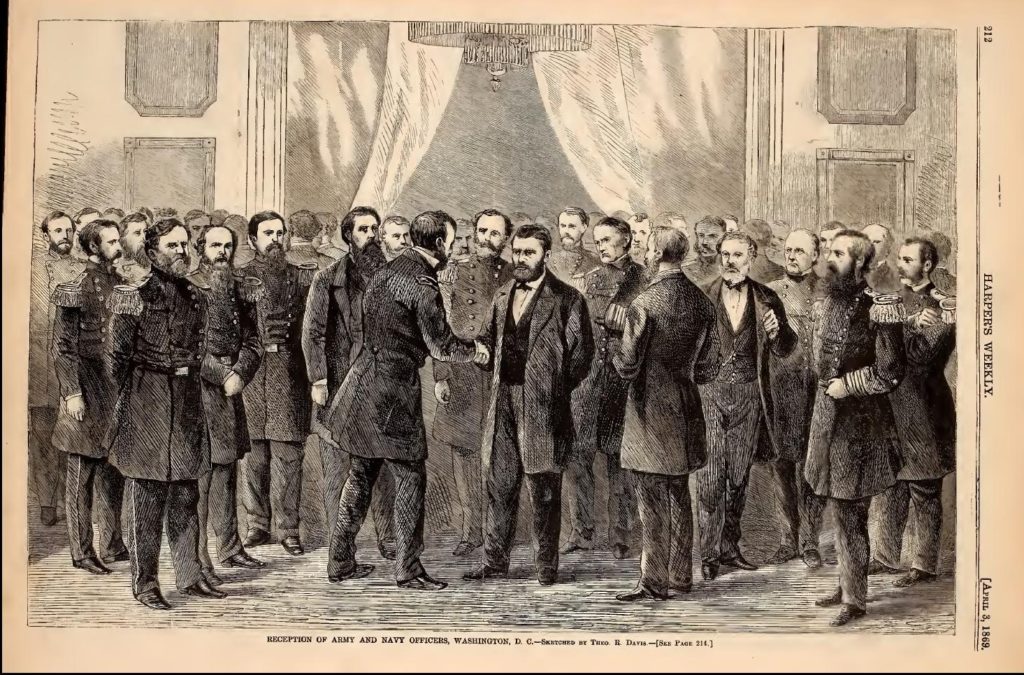

In its March 5, 1869 issue The New-York Times kept coverage of Ulysses S. Grant’s inaugural address off its front page, unlike the previous two inaugurations. The times were certainly different, relatively crisis-free. After all, in 1861 a couple weeks before the federal inauguration, Jefferson Davis had been sworn in as president of the Confederacy, a union of seven breakaway states. After four years of brutal war the states were still disunited in 1865. From the northern perspective progress had been made, but two big armies were still locked in a months-long stalemate on the Eastern Front. Would the war ever end? If the Union prevailed, what was Abraham Lincoln’s approach toward the southern states? March 1869 might not have been as dramatic, but the divisive Andrew Johnson was leaving the White House and the Union’s preeminent war hero was taking his place.

President Grant’s speech might have been so bland that the Times decided to keep it off the front page, but A.J. Langguth has written: “No one had expected Grant on the podium to match the eloquence of Lincoln, but his address was warmly received, as were most of his cabinet appointments when he finally revealed them.”[1]

__________________

And the Times did headline the Cabinet appointments on its front pages. On March 6th it reported that all General Grant’s selections were immediately confirmed by the Senate, but it turned out that there was a problem. Retailer Alexander T. Stewart was President Grant’s pick for Secretary of the Treasury, but that choice violated a 1789 law prohibiting persons engaged in trade from that position. The Senate refused the president’s request to make an exception. Mr. Stewart diplomatically offered his resignation. President Grant replaced him with Radical Republican George S. Boutwell. A couple other changes were made and by March 11th President Grant’s Cabinet was ready to go.

In its April 3, 1869 issue Harper’s Weekly did praise the inaugural address and said that any cabinet would be a disappointment; Mr. Grant’s selections differed from the Lincoln Cabinet filed with “all his rivals”:

THE PRESIDENT.

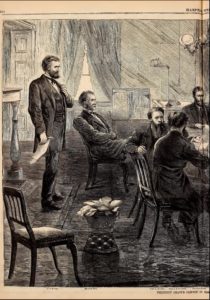

THE President probably did not expect that he was going to avoid trouble by going into the White House, and he is not disappointed. The range of duties and the official methods are different from those to which he has been most accustomed; but he has the sagacity which swiftly adapts itself to changed circumstances, and a certain coolness which enables him justly to weigh reasons. Amidst the tempest of rumors and speculations from Washington, the wise man will fix his eye steadily upon what has been actually said and done by the President, if he would properly estimate the promise of his administration. It is well for every body to remember that for every office in the country there are probably a dozen or more applicants. Consequently the number of the dissatisfied will be enormous, and when a Republican shakes his head doubtfully over the new administration, it will be always an interesting inquiry whether he wished for any thing or had recommended any body, and whether his wishes and recommendation were successful. If, on the other hand, Mr. TOOTS, who thought nothing so democratic and delightful as a slave-holding despotism, suspects General GRANT of monarchical tendencies – why, Mr. TOOTS will be Mr. TOOTS.

The President’s first word was his inaugural. It was brief, pointed, decisive, and admirable. He said that the national honor must be maintained by fulfilling the spirit of the law, and that freedom of opinion must be every where protected. It was an unmistakable sound, the voice of an honest conviction, and a righteous purpose. Until ABRAHAM LINCOLN spoke upon a similar occasion, this country for many a year had not heard at an inauguration any thing becoming an American and a man. Since we have happily emerged from that baleful epoch let any man reflect upon the kind of person that was made President in the latter days of Democratic ascendency [sic], and he will comprehend the immense progress marked by the mere presence of such a man as GRANT in the White House.

The President’s first act was his choice of a Cabinet. Undoubtedly it was a disappointment, as any Cabinet must have been, and the greater disappointment because the previous silence of the President had excited expectations that no that no result could satisfy. Mr. LINCOLN’S plan of calling into his Cabinet all his rivals in the nominating Convention was as severely criticised as that of General Grant in summoning those whom be believed fitted for the duties of their offices. Mr. BUCHANAN’s Cabinet was purely political, signally destitute of ability, and a mere conspiracy. Its single conspicuous member was General Cass, whose recommendation was that he was a thoroughly disciplined Democrat, who had held office immemorially, and had been a candidate for the Presidency. There are obvious reasons why the selection of a cabinet will always be a disappointment. …

[The first bill President Grant was a good law. The Tenure of Office should be repealed, but if not, the Senate shouldn’t hinder President Grant’s choices in his subordinates.]

… The President is not a man to be dismayed by difficulties, and with an able and harmonious Cabinet; with a Congress friendly and not[?] servile; and with the universal confidence of the country, his administration is not likely to disappoint the anticipations which the hope of his election excited.

Modern historian Eric Foner noted that Lincoln picked “the most powerful figures in his party”, but “Grant, coming from a military background, looked upon Cabinet members as ‘staff officers,’ whose main qualification was that they enjoyed his confidence or had done him personal favors. Composed largely of men with little political influence and ‘abilities below mediocrity,’ Grant’s Cabinet seemed oddly detached from the debates over Reconstruction.” Mr. Foner explained that Alexander T. Stewart was the nation’s largest importer, who “did more business with the department he had been chosen to head than any other citizen.” The refusal of Congress to repeal the 1789 law barring Stewart from the Treasury was partly due to his announced intention to replace all the official at the New York Custom House. More broadly, “the rebuff reflected Congressional displeasure at Grant’s evident desire to stand above partisanship.” Grant learned quickly and began to “rely on leading members of Congress for advice and guidance” and did replace Stewart with Radical Boutwell. The overall conservative nature of the Cabinet suggested the finality of Reconstruction. After all, Congress gave its approval to the 15th amendment in February.[2]

![Grant in citizens clothes (Cincinnati, O[hio] : Published by Henry Howe & Middleton, No. 141 Main St. Cincinnati, O., [1868]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2004670273/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/10993v-250x300.jpg)