According to the February 23, 1869 issue of The New-York Times Washington’s Birthday 150 years ago was kind of a humdrum day in the great metropolis, a day that “had the air of something that has missed fire. It was neither like a holiday nor a business day, but a pale colorless negation of both. There were plenty of folks in holiday costume about the streets, but there was nothing to mark the anniversary of Washington’s birthday save a few flags drooping dismally over the City Hall, and a vast concourse of idlers thronging the steps and piazzas of the civic building.” Public offices and many stores were closed, giving much of downtown “a sort of semi-Sabbatical aspect, which, lowered upon by gloomy skies, was extremely depressing.”

The patient crowd at city hall waited in vain for parades or an appearance by the military or fireworks in the evening. There was a bit excitement when a man dressed somewhat in the garb of a Continental Army officer appeared. The people had a lot of fun with “General Washington,” but he turned out to be a photograph vendor. Veterans of the War of 1812 got together to talk over old times and learn about a pension bill stuck in the U.S. Senate. There were some regimental balls around town and a banquet for newsboys.

Things were slightly more exciting for the general public in the nation’s capital:

WASHINGTON, Monday, Feb. 22.

The torchlight display of the Boys in Blue to-night was quite brilliant, notwithstanding the rain. About 3,500 were in line. At 10 o’clock the procession reached the residence of Gen. GRANT, in front of which it halted, the band playing “Hail to the Chief.” A committee of gentlemen representing the organization were introduced to Gen. GRANT, who subsequently reviewed the procession. No speeches were made, Gen. GRANT remarking to the committee that it would be impossible to be heard by the great number, and desiring them to return his thanks to the “Boys in Blue” for their kind consideration. He was pleased to see them celebrating the anniversary of the birth of the “Father of the Country.” Afterward the line of march was again formed, and the procession moved to the residence of Speaker COLFAX, intending to pay their respects to that gentleman, and subsequently called on Senator-elect CARL SCHURZ. …

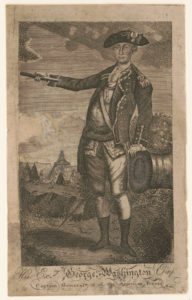

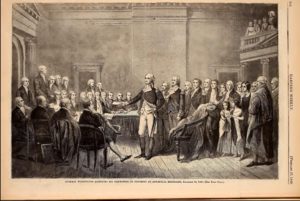

Another New York periodical put an image of George Washington on its cover and described an event from his life that it connected with the upcoming inauguration of President-elect Ulysses S. Grant. From the February 27, 1869 issue of Harper’s Weekly:

WASHINGTON’S RESIGNATION.

In connection with the approaching event of General GRANT’S inauguration as President of the United States – an event destined to be memorable in our history – there is one incident in the career of General WASHINGTON that is especially called to our minds: it is the resignation of his commission as Commander-in-Chief, at Annapolis, December 23, 1883.

For eight years WASHINGTON had devoted his life to the service of his country. The revolution had been accomplished, and the struggling republic began its career as an independent nation. The preceding month had witnessed the evacuation of New York by the British. On the 2d of November WASHINGTON issued his “Farewell Address to the Armies of the United States.” On the 25th he entered New York, where, a few days, later, he took a final leave of his principal officers. After this scene – one of the most touching that is recorded in military annals – he walked in silence to Whitehall, followed by a vast procession, and took his departure for Annapolis, where Congress was about to assemble. Here he arrived on the evening of December 19. The next day he informed Congress of his desire to resign his commission. That body resolved that it should be done at a public audience on the 23d, at noon.The day was fine, and around the State-house a great concourse was assembled. The little gallery of the Senate Chamber was filled with ladies, among whom was Mrs. WASHINGTON. The members of Congress were seated and covered; the spectators were all uncovered. WASHINGTON entered and was led to a chair, when General MIFFLIN, President of Congress, arose and announced the readiness of that body to receive his communications. The Chief, with great dignity and much feeling, delivered a brief speech. “Happy,” said he, “in the confirmation of our independence and sovereignty, and pleased with the opportunity afforded the United States of becoming a respectable nation, I resign with satisfaction the appointment I accepted with diffidence – a diffidence in my abilities to accomplish so arduous a task, which, however, was superseded by a confidence in the rectitude of our cause, the support of the supreme power of the Union, and the patronage of Heaven.” After other remarks he handed his commission to the President, who received it and made an eloquent reply.

After his resignation General WASHINGTON set out for Mount Vernon, All the way from Annapolis, as it indeed it had been from New York, his progress was a triumphal march. …

[The newspaper explained that the image of General Washington was from a painting by Charles Peale Polk. It then presented a detailed history of how the painting came to be in the possession of Lucy Bakewell Audubon, the widow of naturalist John J. Audubon.]

… Every thing relating to WASHINGTON is held in such reverence by mankind that it is an event to present an original picture, which, after a lapse of nearly ninety years, dating from its production, is brought from the seclusion of private life and given to the world.

!["Evacuation day" and Washington's triumphal entry in New York City, Nov. 25th, 1783 (Phil., PA : Pub. [E.P.] & L. Restein, [1879]; LOC: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003652651/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/02468v-300x225.jpg)

![George Washington] / J. Norman sc. (1784; Illus. in: The Boston magazine. Boston, Mass. : Norman & White, 1784 April, frontispiece.; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2004666693/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/3a45481r-150x150.jpg)