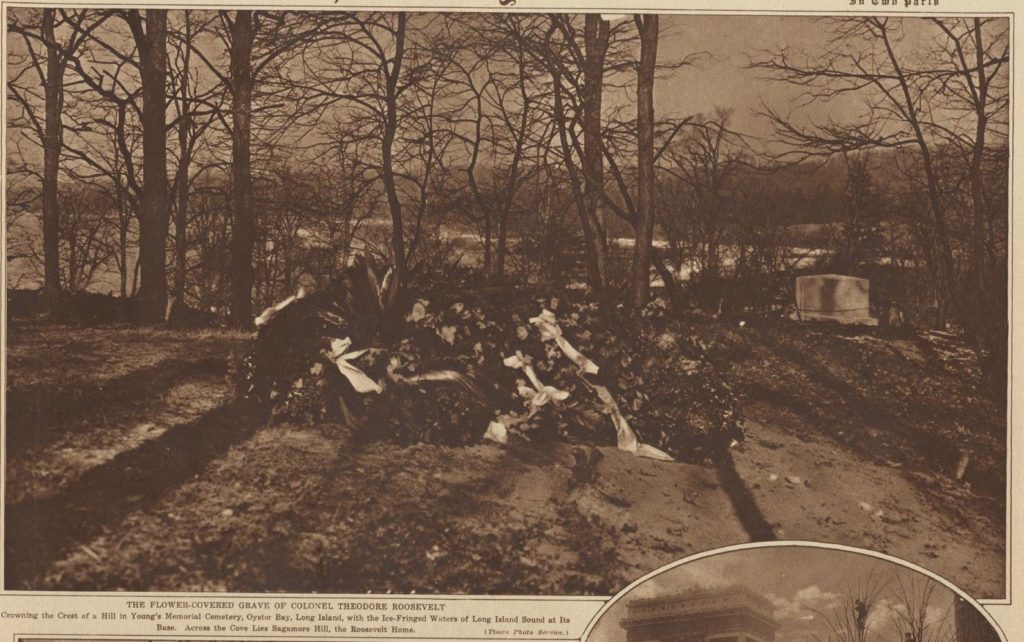

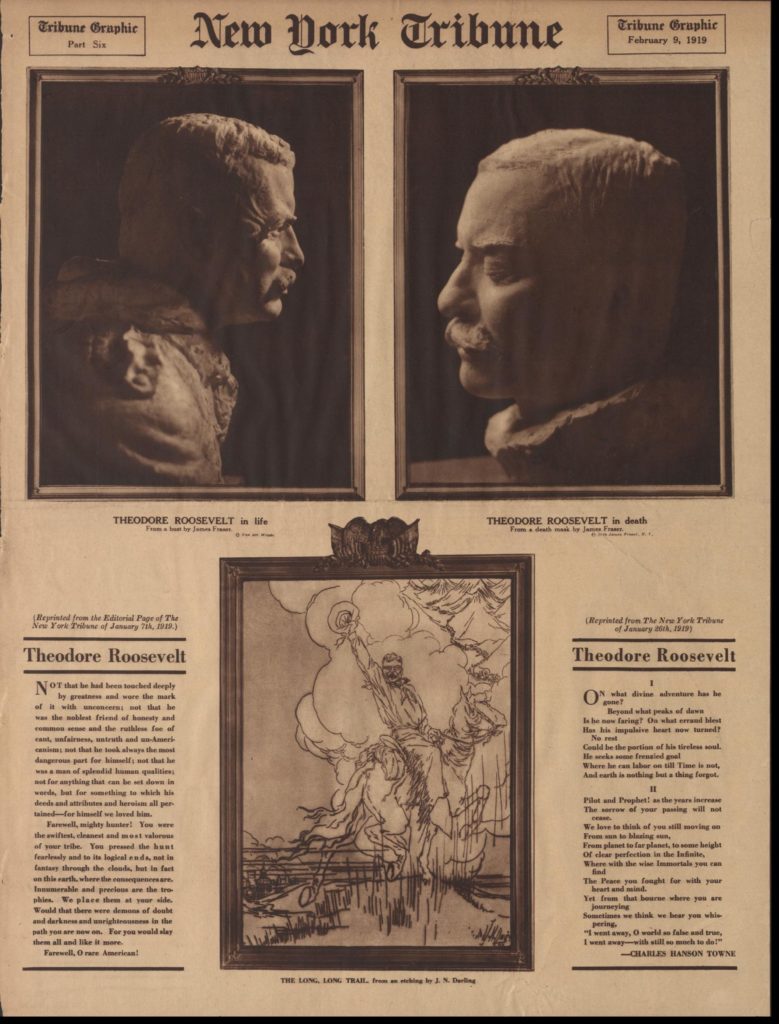

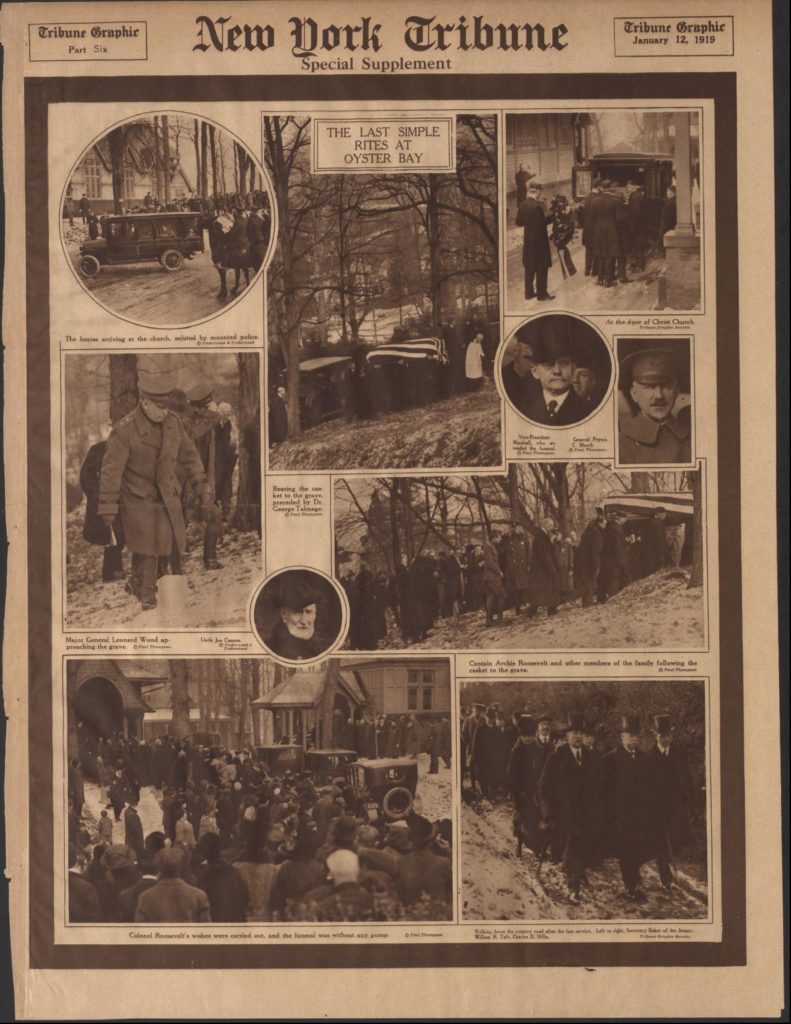

On January 6, 1919 Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th president of the United States, died at his home at Oyster Bay on Long Island. From Europe President Woodrow Wilson telegraphed his order to fly flags at half-staff for thirty days. Mr. Roosevelt’s family followed his wish to have a simple funeral and burial. William Howard Taft, another ex-president, was quoted, “His patriotic Americanism will be missed, of course.”

___________________

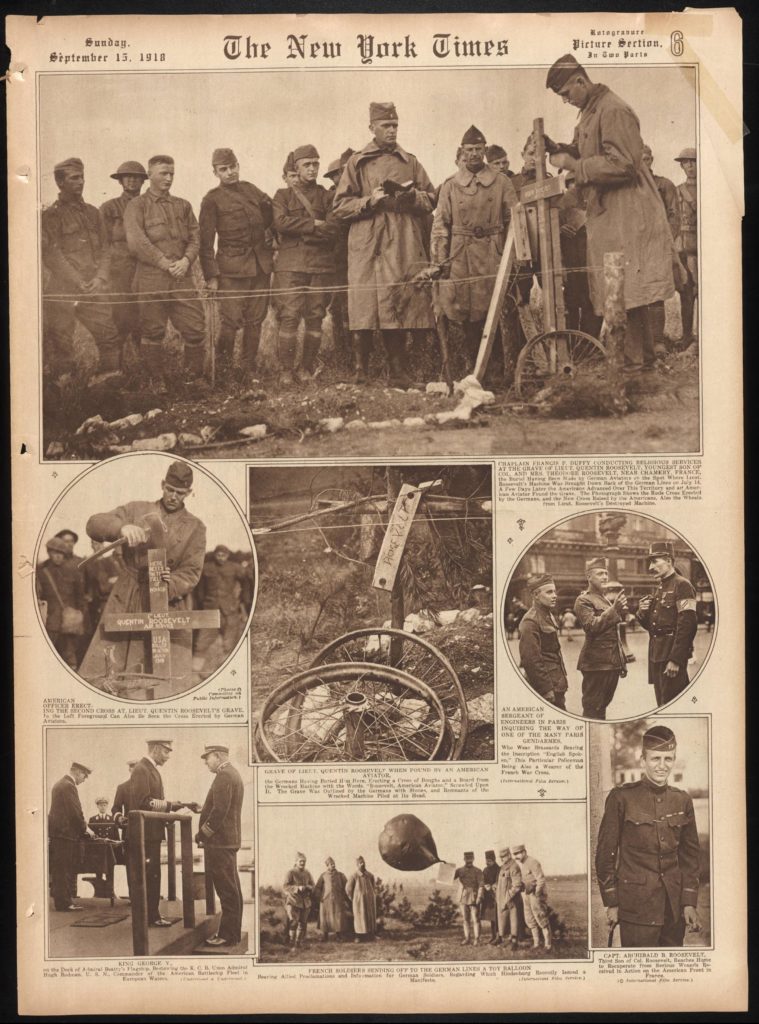

Not quite six months earlier Theodore and Edith Roosevelt’s youngest son Quentin died over there when his plane crashed during a dogfight with Germans. The New York Times on September 15, 1918 pictured Quentin’s grave, which the Germans had originally laid out. The same page showed Quentin’s older brother Archibald returning home after being severely injured in France.

___________________

According to the middle collage above, Theodore Roosevelt was deeply affected when informed of his son’s death and then made this statement from Oyster Bay: “Quentin’s mother and I are very glad that he got to the front and had a chance to render some service to his country and show the stuff there was in him before his fate befell him.”

Theodore Roosevelt’s America and the World War was published in January 1915 (nowadays it’s at Project Gutenberg). In the first paragraph of his Forward Mr. Roosevelt looked back a century to the War of 1812. He compared America at that time to 1914 and criticized President Woodrow Wilson for not doing enough to prepare the United States for war:

In the New York Evening Post for September 30, 1814, a correspondent writes from Washington that on the ruins of the Capitol, which had just been burned by a small British army, various disgusted patriots had written sentences which included the following: “Fruits of war without preparation” and “Mirror of democracy.” A century later, in December, 1914, the same paper, ardently championing the policy of national unpreparedness and claiming that democracy was incompatible with preparedness against war, declared that it was moved to tears by its pleasure in the similar championship of the same policy contained in President Wilson’s just-published message to Congress. The message is for the most part couched in terms of adroit and dexterous, and usually indirect, suggestion, and carefully avoids downright, or indeed straight-forward, statement of policy—the meaning being conveyed in questions and hints, often so veiled and so obscure as to make it possible to draw contradictory conclusions from the words used. There are, however, fairly clear statements that we are “not to depend upon a standing army nor yet upon a reserve army,” nor upon any efficient system of universal training for our young men, but upon vague and unformulated plans for encouraging volunteer aid for militia service by making it “as attractive as possible”! The message contains such sentences as that the President “hopes” that “some of the finer passions” of the American people “are in his own heart”; that “dread of the power of any other nation we are incapable of”; such sentences as, shall we “be prepared to defend ourselves against attack? We have always found means to do that, and shall find them whenever it is necessary,” and “if asked, are you ready to defend yourself? we reply, most assuredly, to the utmost.” It is difficult for a serious and patriotic citizen to understand how the President could have been willing to make such statements as these. Every student even of elementary American history knows that in our last foreign war with a formidable opponent, that of 1812, reliance on the principles President Wilson now advocates brought us to the verge of national ruin and of the break-up of the Union. The President must know that at that time we had not “found means” even to defend the capital city in which he was writing his message. He ought to know that at the present time, thanks largely to his own actions, we are not “ready to defend ourselves” at all, not to speak of defending ourselves “to the utmost.” In a state paper subtle prettiness of phrase does not offset misteaching of the vital facts of national history.

The book began with a poem about war and peace attributed to William Samuel Johnson. According to Wikipedia Mr. Johnson was not in favor of the Revolutionary War and even was temporarily arrested for communicating with the British.

PRAYER FOR PEACE

Now these were visions in the night of war:

I prayed for peace; God, answering my prayer,

Sent down a grievous plague on humankind,

A black and tumorous plague that softly slew

Till nations and their armies were no more–

And there was perfect peace …

But I awoke, wroth with high God and prayer.

I prayed for peace; God, answering my prayer,

Decreed the Truce of Life:–Wings in the sky

Fluttered and fell; the quick, bright ocean things

Sank to the ooze; the footprints in the woods

Vanished; the freed brute from the abattoir

Starved on green pastures; and within the blood

The death-work at the root of living ceased;

And men gnawed clods and stones, blasphemed and died–

And there was perfect peace …

But I awoke, wroth with high God and prayer.

I prayed for peace; God, answering my prayer,

Bowed the free neck beneath a yoke of steel,

Dumbed the free voice that springs in lyric speech,

Killed the free art that glows on all mankind,

And made one iron nation lord of earth,

Which in the monstrous matrix of its will

Moulded a spawn of slaves. There was One Might–

And there was perfect peace …

But I awoke, wroth with high God and prayer.

I prayed for peace; God, answering my prayer,

Palsied all flesh with bitter fear of death.

The shuddering slayers fled to town and field

Beset with carrion visions, foul decay.

And sickening taints of air that made the earth

One charnel of the shrivelled lines of war.

And through all flesh that omnipresent fear

Became the strangling fingers of a hand

That choked aspiring thought and brave belief

And love of loveliness and selfless deed

Till flesh was all, flesh wallowing, styed in fear,

In festering fear that stank beyond the stars–

And there was perfect peace …

But I awoke, wroth with high God and prayer.

I prayed for peace; God, answering my prayer,

Spake very softly of forgotten things,

Spake very softly old remembered words

Sweet as young starlight. Rose to heaven again

The mystic challenge of the Nazarene,

That deathless affirmation:–Man in God

And God in man willing the God to be …

And there was war and peace, and peace and war,

Full year and lean, joy, anguish, life and death,

Doing their work on the evolving soul,

The soul of man in God and God in man.

For death is nothing in the sum of things,

And life is nothing in the sum of things,

And flesh is nothing in the sum of things,

But man in God is all and God in man,

Will merged in will, love immanent in love,

Moving through visioned vistas to one goal–

The goal of man in God and God in man,

And of all life in God and God in life–

The far fruition of our earthly prayer,

“Thy will be done!” … There is no other peace!

WILLIAM SAMUEL JOHNSON.

From the Library of Congress: material from the January 12, 1919 New York Tribune and September 15, 1918 New York Times; Quentin’s victory and his death; roll call, pony, and portrait (there are also a lot of photos of Quentin with his mother during the White House years); stereograph; Puck July 27, 1898, leading the charge

_____________________________________

January 14, 2019 – I found this Saturday, also at the Library:

____________________________________

January 27, 2019

The Trib had more in its February 19, 1919 issue

![Grave of Lieut. Quentin Roosevelt, buried by Germans where he fell (Meadville, Pa. ; New York, N.Y. ; Chicago, Ill. ; London, England : Keystone View Company, [photographed between 1914 and 1918, published 1923]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2016646022/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/1s04231v-300x154.jpg)

![Grave of Lieut. Quentin Roosevelt, buried by Germans where he fell (Meadville, Pa. ; New York, N.Y. ; Chicago, Ill. ; London, England : Keystone View Company, [photographed between 1914 and 1918, published 1923] LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2016646022/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/2s04231v-300x152.jpg)