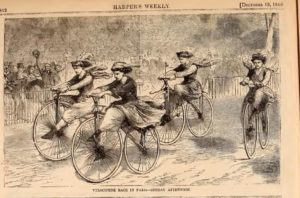

The times they are a-modernizin’. Back in April 1868 an American periodical urged better preservation of historically important places. 150 years ago this month the same paper enthusiastically described a new device – a traveling machine. It wasn’t just the very high speeds possible – up to ten miles per hour on the streets of Paris – that was so appealing; the paper consulted medical experts, who determined that there were health benefits for those who used the new contraption. Technical experts at Scientific American contrasted the new American models with the French tries. A famous preacher was an early adopter. Another man reportedly used the machine for a quicker and more enjoyable commute. Schools of instruction opened, and there were even organized races in Paris. The new device compared favorably with old technology (the four-legged type).

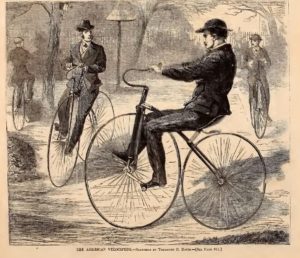

From the December 19, 1868 issue of Harper’s Weekly:

THE AMERICAN VELOCIPEDE.

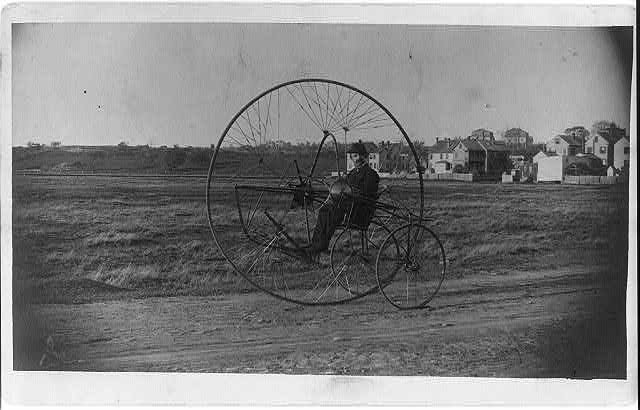

SOME months have passed since we heard of the advent in Paris of a strange something on which it was possible for an active Frenchmen, furnishing his own motive power, to traverse ten miles of the streets of Paris during a single hour. It was a bicircle, a veloce. It was a two-wheeled contrivance, and something decidedly new.

There seemed to be no very definite information with reference to the machine. It was like Paris – fast; and, unlike the generality of French contrivances, seemed likely to be useful.

The fever which raged so high in France seems to have broken out in America. The veloce was inspected by ingenious Americans, and a number of professional inventors are now laboring to bring it to American completeness. A few persons in New York have the velocipede for sale, and are doing quite as driving a business as the riders of their wares.

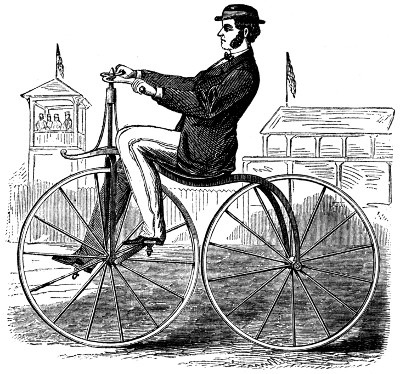

The machines now offered for sale are four-wheeled, three-wheeled, and two-wheeled. The first two may be used tolerably well during a first trial, but the two-wheeled affair needs acquaintance before one may ride it successfully. Then it is incomparably the best, for its movement is graceful and easy. The power required for driving it is but little, when the machine is properly made. Of the various velocipedes yet produced the American seems to be the best, for various reasons. It does not, like the French machine, contract the chest; it is simpler, lighter, and withal stronger and more durable. The constructor took great pains to obviate the decided objection to the French machine – that of retarding rather than assisting the development of the chest – and constructed his patterns under the advice of one of the best surgeons in New York, who, with others, now recommends the velocipede as an excellent means for healthful pleasure. The Scientific American says: “The reach, or frame, is made of hydraulic tubing. PICKERING’S is made by gauge, just as sewing-machines, Waltham watches, and Springfield muskets are made, so that when any part wears out or is broken it may be replaced at an hour’s notice. Its bearings are of composition or gun metal, and the reach or frame is tubular, giving both lightness and strength. The hub of the hind wheel is bushed with metal, and the axle constitutes its own oil-box. It differs from the French veloce in the arrangement of the tiller, which is brought well back and is sufficiently high to allow of a perfectly upright position in riding. The stirrups or crank pedals are three-sided, with circular flanges at each end; and, as they are fitted to turn on the crank pins, the pressure of the foot will always bring one of the three sides into proper position. They are so shaped as to allow of the use of the fore part of the foot, bringing the ankle joint into play, relieving the knee, and rendering propulsion much easier than when the shank of the foot alone is used, as in propelling the French vehicle. The connecting apparatus differs from that of the French bicycle in that the saddle bar serves only as a seat and a brake, and is not attached to the rear wheel. By a simple pressure forward against the tiller, and a backward pressure against the tail[?] of the saddle, the saddle-spring is compressed and the brake attached to it brought firmly down upon the wheel.”

A number of persons in this city and its vicinity are already making use of the velocipede as a means of traversing the distance from their homes to and from their places of business. One gentleman takes his ride of nearly ten miles daily, and saves time as well as enjoying the ride. The Rev. HENRY WARD BEECHER has secured two of the American machines, and other gentlemen, well known in the literary and artistic world, are possessed of their magic circles.

Schools for the instruction of velocipede-riding are being opened. Youngsters ride down Fifth Avenue with their school-books strapped in front of their velocipedes, and expert riders cause crowds of spectators to visit the public squares, which afford excellent tracks for the light wheels to move swiftly over.

The best speed thus far attained is a mile in a few seconds less than four minutes. In Paris the Americans carried off the prizes, as well for slow as fast riding. The slow riding is much the more difficult, as it is far easier for the rider to keep his equilibrium in a rapid ride than while moving slowly – just as in the case of a boy driving his hoop, the faster it goes the more direct is its line. To ride a velocipede well is much less difficult than to learn to skate, and the danger of a fall is not imminent. The present scale of prices demanded by dealers is about the same, ranging from sixty to one hundred dollars.

“A horse costs more, and will eat, kick, and die; and you cannot stable him under your bed,” remarked an expert rider to a friend.

The weight of a medium-sized velocipede is about sixty pounds, and the size of driving wheel most in favor from 30 to 36 inches in diameter. The springs of the vehicle are so arranged as to make it ride easily over a tolerably rough pavement. A fair country road is a good a track as one could desire; but hills of more than one foot ascent in twenty cannot be climbed without dismounting and leading the machine.

The winter season is not favorable to veloce-riding, but with opening of spring we may expect to see the two-wheeled affairs gliding gracefully about the streets and whizzing swiftly through the smooth roads of the Park.

According to Edward W. Byrn’s The Progress of Invention in the Nineteenth Century (1900, at Project Gutenberg), before mid-century cycling devices required striking the toes on pavement for propulsion (like a modern skateboard). Pedals began being used extensively after 1866. People enthusiastically took to the velocipede, even though their heavy wooden wheels made them “bone-shakers”:

However superior to other animals man may be in point of intellect, it must be admitted that he is vastly inferior in his natural equipment for locomotion. Quadrupeds have twice as many legs, run faster, and stand more firmly. Birds have their two legs supplemented with wings that give a wonderfully increased speed in flight, and fish, with no legs at all, run races with the fastest steamers; but man has awkwardly toddled on two stilted supports since prehistoric time, and for the first year of his life is unable to walk at all. That he has felt his inferiority is clear, for his imagination has given wings to the angels, and has depicted Mercury, the messenger of the gods, with a similar equipment on his heels. We see the ambition for speed exemplified even in the baby, who crows in exhilaration at rapid movement, and in the boy when the ride on the flying horses, the glide on the ice, or the swift descent on the toboggan slide, brings a flash to his eye and a glow to his cheeks.

A characteristic trend of the present age is toward increased speed in everything, and the most conspicuous example of accelerated speed in late years is the bicycle. It has, with its fascination of silent motion and the exhilaration of flight, driven the younger generation wild with enthusiasm, has limbered up the muscles of old age, has revolutionized the attire of men and women, and well-nigh supplanted the old-fashioned use of legs. It is the most unique and ubiquitous piece of organized machinery ever made. The thoroughfares and highways of civilization fairly swarm with thousands of glistening and silently gliding wheels. It is to be found everywhere, even to the steppes of Asia, the plains of Australia, and the ice fields of the Arctic.

The true definition of the bicycle is a two-wheeled vehicle, with one wheel in front and the other in the rear, and both in the same vertical plane. Its life principle is the physical law that a rotating body tends to preserve its plane of rotation, and so it stands up, when it moves, on the same principle that a top does when it spins or a child’s hoop remains erect when it rolls.

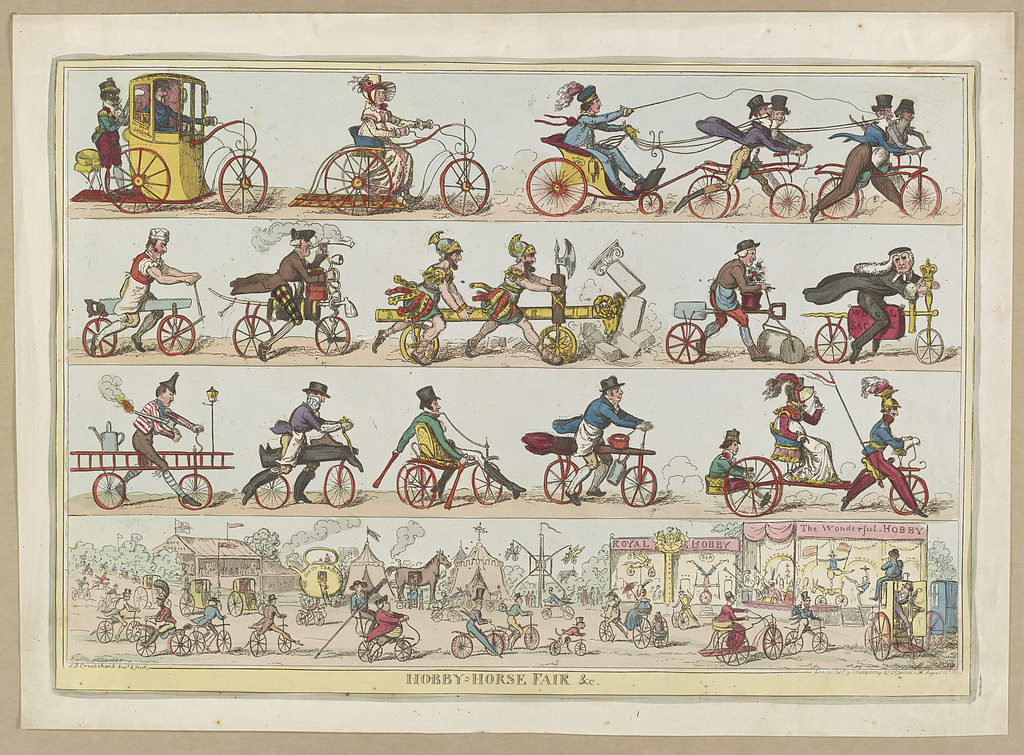

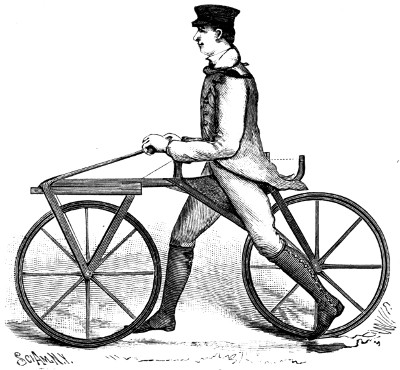

A form of carriage adapted to be propelled by the muscular effort of the rider was constructed and exhibited in Paris by Blanchard and Magurier, and was described in the Journal de Paris as early as July 27, 1779, but the true bicycle was the product of the Nineteenth Century. It was invented by Baron von Drais, of Manheim-on-the Rhine. See Fig. 180. It consisted of two wheels, one before the other, in the same plane, and connected together by a bar bearing a saddle, the front wheel being arranged to turn about a vertical axis and provided with a handle for guiding. The rider supported his elbows on an arm rest and propelled the device by striking his toes upon the ground, and in this way thrusted himself along, while guiding his course by the handle bar and swivelling front wheel. This machine was called the “Draisine.” It was patented in France for the Baron by Louis Joseph Dineur, and was exhibited in Paris in 1816. In 1818 Denis Johnson secured an English patent for an improved form of this device, but the principle of propulsion remained the same. This device, variously known as the “Draisine,” “vélocipède,” “célérifère,” “pedestrian curricle,” “dandy horse,” and “hobby-horse,” was introduced in New York in 1819, and was greeted for a time with great enthusiasm in that and other cities.

On June 26, 1819, William K. Clarkson was granted a United States patent for a vélocipède, but the records were destroyed in the fire of 1836. In 1821 Louis Gompertz devised an improved form of “hobby-horse,” in which a vibrating handle, with segmental rack engaging with a pinion on the front wheel axle, enabled the hands to be employed as well as the feet in propelling the machine. Such devices all relied, however, upon the striking of the ground with the toes. Their fame was evanescent, however, and for forty years thereafter little or no attention was paid to this means of locomotion, except in the construction of children’s carriages and velocipedes having three or more wheels.

In 1855 Ernst Michaux, a French locksmith, applied, for the first time, the foot cranks and pedals to the axle of the drive wheel. A United States patent, No. 59,915, taken Nov. 20, 1866, in the joint names of Lallement and Carrol, represented, however, the revival of development in this field. Lallement was a Frenchman, and built a machine having the pedals on the axle of the drive wheel, and it was at one time believed that it was he who deserved the credit for this feature, but it is claimed for Michaux, and the monument erected by the French in 1894 to Ernest and Pierre Michaux at Bar le Duc gives strength to the claim. The bicycle, as represented at this stage of development, is shown in Fig. 181. In 1868-’69 machines of this type went extensively into use. Bicycle schools and riding academies appeared all through the East, and notwithstanding the excessive muscular effort required to propel the heavy and clumsy wooden wheels, the old “bone-shaker” was received with a furor of enthusiasm. …

And the innovations continued during the rest of the century, including the sprocket chain and pneumatic tire, until the “safety” bicycle appeared: “Its diamond frame of light but strong tubular steel, its ball bearings, its suspension wheels and pneumatic tires impart to the modern bicycle strength with lightness, and beauty with efficiency, to a degree scarcely attained by any other piece of organized machinery designed for such trying work.” By 1899 a bicycle broke a one minute mile behind a train’s wind break.

![Velocipede brace / lith. of Henry Seibert & Bros. Ledger Building [cor. Wi]lliam & Spruce Sts. ([New York] : Lith. of Henry Seibert & Bros. Ledger Building [cor. Wi]lliam & Spruce Sts. [N.Y.], [1869]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2017651501/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/12690v-150x150.jpg)

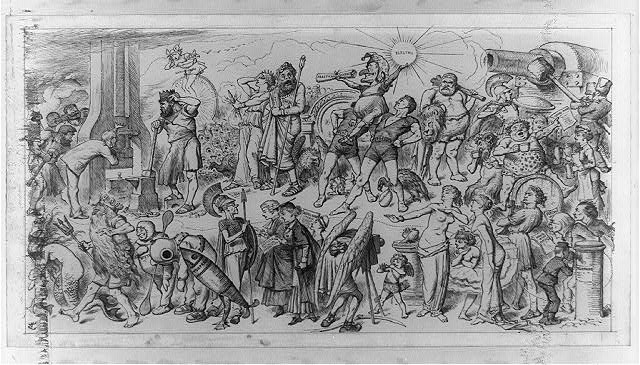

![The spirit moving the Quakers upon worldly vanities!! / Yedis, invt. ([London] : Pubd. by J Sidebethem, 287 Strand, 1819. ; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2006689059/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/04978v-1024x742.jpg)