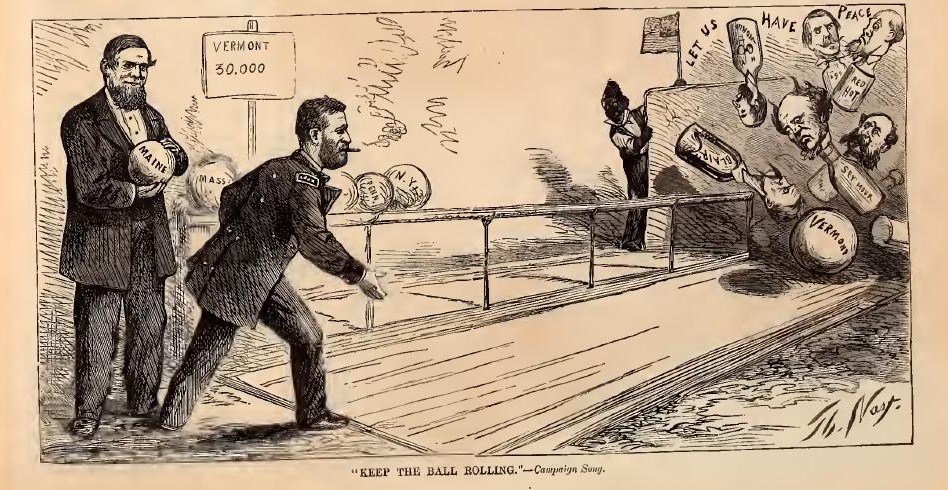

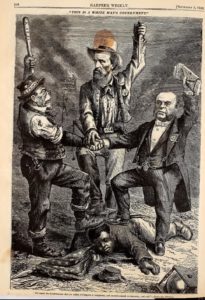

Some headlines from early September 1868. Statewide elections in Vermont resulted in large Republican majorities. The Georgia legislature expelled twenty-five black representatives (New York Times September 4, 1868). After a conference at White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, Union General William Rosecrans conducted a public correspondence with Confederate General Robert E. Lee about “what the South wants.” The general’s letter was controversial. A northern periodical contrasted General Lee’s words of conciliation with the expulsion of the black legislators in Georgia and other southern white actions against the freed slaves. The editorial tied the letter to the 1868 campaign.

______________________

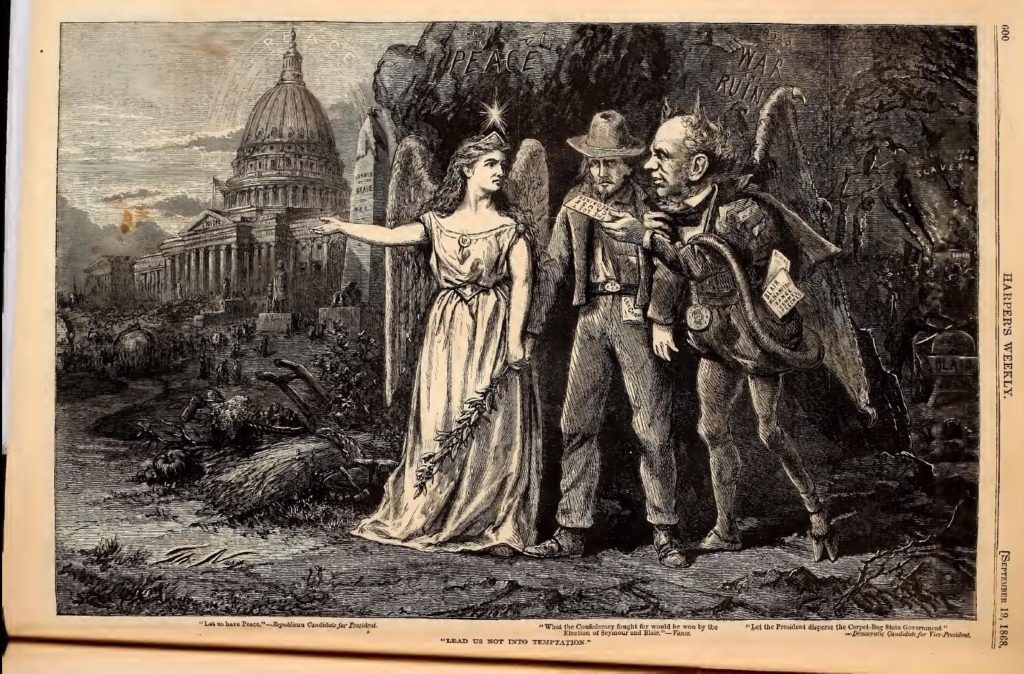

From Harper’s Weekly September 19, 1868 (page 595):

GENERAL ROSECRANS AND GENERAL LEE.

One of the lighter comedies of the canvass is the exchange of letters between General ROSECRANS and the ex-rebel Generals LEE, BEAUREGARD, and others. General LEE, whose whole career shows him to be one of the weakest of men, and whose treachery to the Government was not less contemptible than odious, is saluted by General ROSECRANS in these words: “I know you are a representative man in reverence and regard for the Union, the Constitution, and the welfare of the country.” The General then asks the representative man to tell him the public opinion of the South.” Conferring with other representative men, like BEAUREGARD, of “booty and beauty” renown, General LEE replies in a series of statements which shows that he is not familiar with the recent history of the Southern States. Indeed, a grosser misrepresentation of familiar public facts has not been made.

But one assertion is peculiarly amusing in view of the expulsion of the Georgia colored members, of the Ku-Klux Klan, of the address of the South Carolina Committee, and of WADE HAMPTON’S scheme of Democratic voting or starvation. It is the remark of General LEE that “the idea that the Southern people are hostile to the negroes or would oppress them if it were in their power to do so is entirely unfounded. They have grown up in our midst, and we have been accustomed from childhood to look upon them with kindness.” The paddle, the auction-block, and the blood-hound were the emblems of this kindness before the war; the Black Codes and the massacres, since.

The letter of General LEE is put forward as a Democratic campaign document, and it is one of the feeblest conceivable.

The complete letter from Lee and twenty-six other southern men (Beauregard, Stephens, Letcher) to Rosecrans was published in the September 8, 1868 issue of the Staunton Spectator. You can read it at The Lee Family Digital Archive.

According to the Library of Congress, long-time social reformer Gerrit Smith wrote Robert E. Lee a letter on September 25, 1868 severely criticizing the general’s letter as promoting a “re-instatement of slavery.” “But to argue to you that slavery, virtual, if not literal, must ever attend the disfranchisement of a race, and especially when it is the only disfranchised race, would be a superfluity insulting to your excellent understanding.” Mr. Smith’s letter also referenced the upcoming election:

… How sad that the white men of the South should look upon the Republican Party as the enemy of the South! In the success of this Party—in the election of those just and wise men, Grant and Colfax—is the salvation of the South. Peace—a righteous and enduring Peace—would come of it. The white men of the South have but two enemies. The Republican Party is neither of them. Their own wicked hearts—wicked, because still refusing to repent of slavery—is one of them; and the other, and far wickeder one, is the Democratic Party, whose only hope of re-ascendency being in the resurrection of slavery, is ever at work to inflame those wicked hearts, and to counsel and contrive that resurrection.

You white men of the South have made your choice. This choice is to go for the Democratic Party. You will, probably, be disappointed in the Election. For the North, though extensively corrupted by the arts of the leaders of the Democratic Party, can hardly be brought to give a majority of her votes to a Party, which goes openly for cheating the Nation’s creditors, and for taking up arms to bring back under the yoke of slavery a race to whose magnanimous forgetfulness of their immeasurable wrongs and to whose brave hearts and stalwart arms the salvation of our country is so largely due. …

In his P.S. Gerrit Smith referred to the Democrats as the “Murder-Party” because in the three years since the war ended they had killed over a thousand southerners for their political opinions.

In his 1901 The Reconstruction of Georgia (beginning on page 56 at Project Gutenberg) Edwin C. Woolley wrote about the expulsion of the black legislators, which happened “the very moment after the federal government withdrew its hand”:

THE EXPULSION OF THE NEGROES FROM THE LEGISLATURE

AND THE USES TO WHICH THIS EVENT WAS APPLIED

When the Georgia Republicans, or Radicals, as they were locally called, found that instead of a sweeping victory they had won only a governorship hemmed in by a hostile legislature, an effort was made, as we have said, to improve their position through the interference of Meade. Meade refused to aid them. When, a short time afterwards, federal power, on which they had hitherto relied, was completely withdrawn, they seemed left to make the best of an uncomfortable position without any assistance. At this point a god appeared from the machine.

In the state senate there were three negroes, in the lower house twenty-five. Their presence was an offense. It was an offense not merely to the Conservative members. Some of the Republicans entertained Conservative sentiments and principles, but supported reconstruction simply in order to hasten the liberation of the state from Congressional interference. To them as well as to the Conservatives “negro rule” was obnoxious. Negro rule, so far as it consisted in negro suffrage, was established by the constitution. But negro office-holding was not so established expressly. As early as July 25, 1868, the question, whether negroes were eligible to the legislature, was raised in the state senate.

Legally considered, the question had two sides, each supported by eminent lawyers. For the negroes it was argued that Irwin’s Code, which was made part of the law of the state by the constitution, enumerated among the rights of citizens the right to hold office. Negroes were made citizens of equal rights with all other citizens by the new constitution. Therefore they had the right to hold office. It was true that the constitution did not grant the right to hold office to the negroes expressly, as it granted the right to vote; but in view of the fact that the convention which made the constitution was elected by 25,000 white and 85,000 colored men, and that that constitution was adopted by 35,000 white and 70,000 colored men, it would be absurd to suppose that the intent of that instrument was to withhold office from the negroes. On the other side, it was argued that the right to hold office did not belong to every citizen, but only to such citizens as the law specially designated, or to such as possessed it by common law or custom. Irwin’s Code could not be cited to prove that negroes had the right, because that law had been enacted before the negroes had been made citizens, and the word citizens in it referred to those who were citizens at that time. As the negro had no right to hold office because he was a citizen, and as he could not claim the right from common law or custom, he could obtain it only by specific grant of law. There was no such grant. The argument for the negro was made by the Supreme Court of the state in 1869, the opposing argument by one of the justices of that court in a dissenting opinion.

Such were the legal aspects of the question, which were of course less important than the political and the emotional aspects. The legislature passed upon the issue in the early part of September, 1868, by declaring all the colored members ineligible, and admitting to the vacated seats the candidates who had received respectively the next highest number of votes. If there was some legal ground for unseating the negroes, there was none for seating the minority candidates. It was done on the authority of the clause in Irwin’s Code which said:

If at any popular election to fill any office the person elected is ineligible, … the person having the next highest number of votes, who is eligible, whenever a plurality elects, shall be declared elected.

But this clause is found under the title “Of the Executive Department,” and under the sub-head “Regulations as to All Executive Offices and Officers.” Under the next title “Of the Legislative Department,” there is no such provision.

For a legislature to unseat some of the elected members because on not untenable legal grounds it finds them ineligible, is not unusual. But the act of the Georgia legislature could not, under the circumstances, be regarded in the ordinary way. It showed strong racial prejudice. It was a startling breach of the system which reconstruction had been designed to institute, committed the very moment after the federal government withdrew its hand. It fixed on Georgia at once the earnest and unfavorable attention of northern public opinion. This fact enabled the Georgia Republicans to bring the federal government again to their assistance.

On the pages right after it used the expulsion of the black legislators as an example of how Robert E. Lee was out of touch with Southern reality, Harper’s Weekly reported on three Georgia cities that were looking pretty good after a little Republican reconstruction:

2018 sure has been impinging on my enjoyment of 1868; I’m glad I could put this up by early fall. All the Harper’s Weekly clippings were published in issues throughout September 1868 and can be found at the Internet Archives. Theodor Horydczak’s photo of the Lee statue in Statuary Hall at the U.S. Capitol is from the Library of Congress. The Capitol’s first cornerstone was laid 225 years ago on Wednesday, September 18, 1793.

October 1, 2018: According the the October 20, 1918 issue of The New York Times (image 14 at the Library of Congress 100 years ago General and Mrs. Robert E. Lee’s last surviving child was knitting for American soldiers in World War I. According to Find A Grave the 83 year old Mary Custis Lee died on November 22, 1918. An blog at WETA explains that in 1902 Miss Lee was arrested in Alexandria, Virginia for breaking the city’s new segregation law by riding in the black section of a streetcar. Her refusal to give up her seat in the back of the car might have had to do more with personal convenience than as a stand for racial integration. Miss Lee apparently was quite a traveler. In his Freedom by the Sword blog Jimmy Price wrote that General Lee’s daughter was in Europe when World War I broke out. In London on her way back to the States she gave an interview to a The New York Times reporter on October 21, 1914: “I am a soldier’s daughter,” she said, “and descended from a long line of soldiers, but what I have seen of this war, and what I can foresee of the misery which must follow, have made me very nearly a peace-at-any-price woman.”