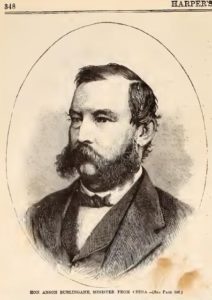

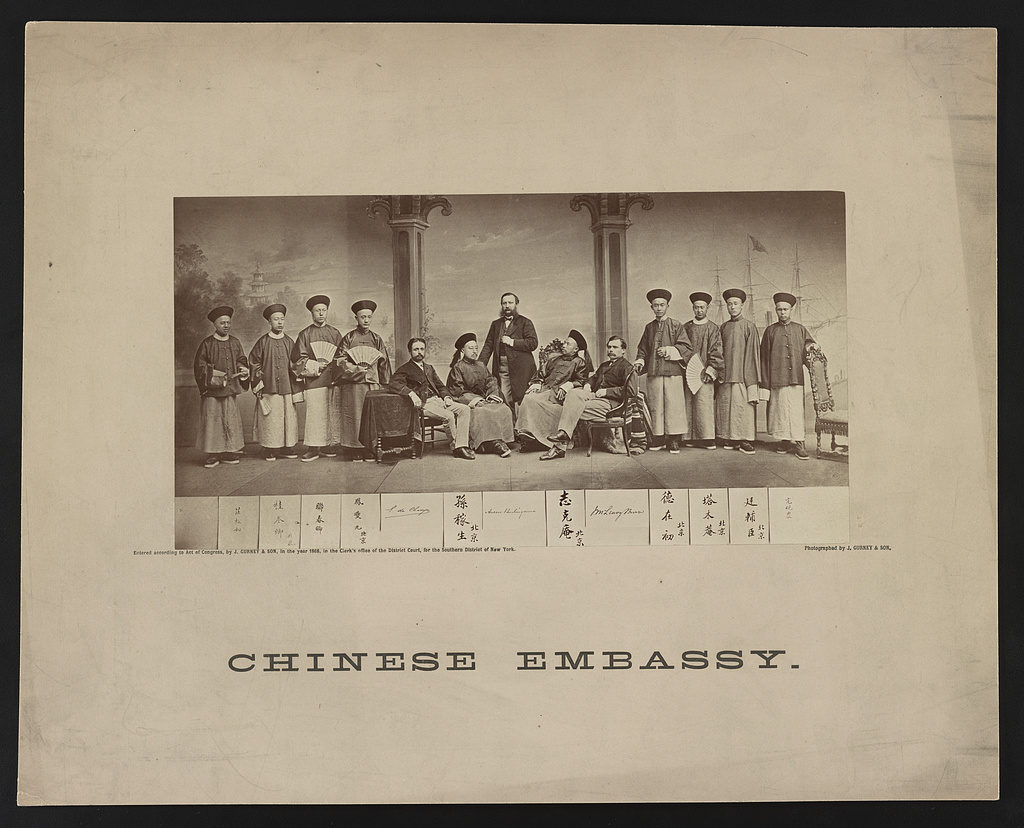

China appreciated the Burlingame treatment. In the fall of 1867 the ambassador notified U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward that he wanted to return to America and resume his political career. The Chinese had different ideas. In November Chinese officials asked Mr. Burlingame if he would act as the Qing Empire’s envoy to the Western powers.

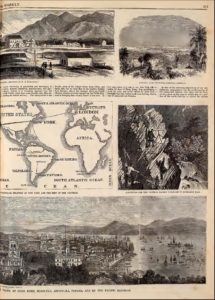

As a very interesting article at Foreign Affairs points out, the ambassador accepted. He notified Secretary Seward with a telegram in November, “And with that, Burlingame went from being the representative of the United States in China to being the representative of China to the world.” Burlingame and two native Chinese ministers began their round-the-world mission in December 1867. They arrived in San Francisco Bay on March 31, 1868. “Burlingame’s arrival in San Francisco was highly anticipated, and people gathered at the wharf to get their first glimpse of Chinese nobility—and of the imperial yellow dragon flag, which appeared in many contemporary press reports. ”

Since the transcontinental railroad wasn’t completed yet, the mission next traveled to the East Coast by steamship via Panama. In early June the group met President Andrew Johnson at the White House. While in Washington Ambassador Burlingame and Secretary Seward negotiated the Burlingame Treaty, which modified and mollified one of the “unequal treaties.”

In early August 1868 the Chinese Embassy stopped in Secretary of State Seward’s hometown of Auburn, New York on its way to Niagara Falls. Walter Stahr writes that Mr. Seward, who had regaled the Chinese mission in Washington with trips to Mount Vernon and the Capitol and with a reception in his DC residence, held a reception for the travelers at the Seward mansion (I believe). “His guest list included not only various local leaders but also such national leaders of the women’s movement as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Margaret Coffin Wright. When one of the senior Chinese praised the intelligence of the American women, Seward’s sister-in-law Lazette Worden responded that ‘Chinese women would be intelligent also, if they were allowed to come into the parlor, instead of being kept in the back part of the house.’ Stanton recalled that the only answer of the Chinese delegates to the women’s questions about Chinese society was ‘immoderate laughter.’ The interpreters explained that the Chinese had never before heard ‘women in all earnestness ask such profound questions.'”[1]

According to reports in The New-York Times, the Chinese also visited Auburn’s prison, where they were favorably impressed by “the American mode of punishing criminals.” The group also intended to visit a nearby farm to see a mower and reaper exhibition. They got rained out on their first try. On August 7th Secretary Seward hosted a second reception for the Embassy before its departure for Niagara on the next day [I don’t know which reception the famous women attended]. Anson Burlingame offered a toast: “The Great Secretary CANNING said that he had called a new world into existence to redress the balance of the old. Mr. SEWARD has called an old world into the existence of the new.”

At Niagara Falls the Chinese hosted a party for the citizens of Buffalo on August 11. Later in August the Embassy was in Boston. On August 21st the City Council put on a banquet for the visitors. You can read about it the Internet Archives. Ralph Waldo Emerson remarked that the Chinese Embassy was a visit “from the oldest Empire in the world to the youngest Republic.” Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.also used that theme in a poem he recited for the occasion. His vision was of a more united world.

As the Foreign Affairs article explains, the Embassy continued to Britain and Europe and ended up in Russia. Mr. Burlingame was probably hoping to draft a treaty that would end the China-Russia border dispute, “But he fell ill in the cold Russian winter, took to bed, and died a few days later, on February 23, 1870. The cause of death was pneumonia. He was 49 years old.”

The same article mentions that the American Civil War was not nearly as destructive as what was going on China at the same time: “When Burlingame arrived in China in October 1861, the ruling Qing Dynasty was fighting the Taiping rebellion in a protracted civil war that lasted from 1851 until 1864. Historians widely consider the Taiping rebellion the bloodiest civil war in history, with an estimated death toll of at least 20 million. Burlingame put the U.S. government firmly on the side of the Qing government.”

Other blue-gray touches. From the Harper’s Weekly biographical sketch (page 346): “At the request of Mr. BURLINGAME Confederate pirates were excluded from Chinese waters.” The Boston banquet was attended by people we’ve had on before: Charles Sumner, who was the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee at the time; Congressman George Boutwell; General Irvin McDowell, who successfully got the Union army headed south after the rebels in July 1861 but unsuccessfully attacked them at First Bull Run; political General Nathaniel P. Banks, who had returned to politics in 1865 and was representing the Massachusetts 6th District in Congress.

I haven’t done a scientific study, but it’s pretty certain that Harper’s Weekly was not a fan of President Andrew Johnson. However, in its June 20, 1868 issue the newspaper seemed to have approved of at least one of Mr. Johnson’s utterances: “In receiving the Chinese Embassy the president made a discursive oration in which he naturally spoke of the means of communication between China and the United States, and remarked that more important than all of them was ‘the great work of connecting the two oceans by a ship-canal to be constructed across the Isthmus of Darien.'” (page 387) I don’t think I ever heard anyone refer to Andrew Johnson as a visionary, so I was very impressed that he thought of a canal across the isthmus about 36 years before the United States began building one. It was just more history I didn’t know. According to Wikipedia Holy Roman Emperor Charles V was dreaming of a canal way back in 1534.

In its May 30th issue Harper’s Weekly recognized that the possibility of increased trade with China would make the Pacific Ocean, the Isthmus of Panama, and the completion of the transcontinental railroad in the United States more important than ever.

You can read Stanton Jue’s article about Anson Burlingame and his missions at American Diplomacy. The article includes an image of President Johnson receiving the Chinese mission.

Sodacan’s image of the Qing flag (1862-1889) is licensed by Creative Commons. The portrait of Oliver Wendell Holmes is from a book of his works at Project Gutenberg. All the images and references from Harper’s Weekly of 1868 can be found at the Internet Archives May 30th, June 13th, and July 18th. From the Library of Congress: Administrative map of Qing Dynasty about 1900, Niagara-Falls, N.Y. 1882, Chinese Embassy

September 2, 2018 – This just in:

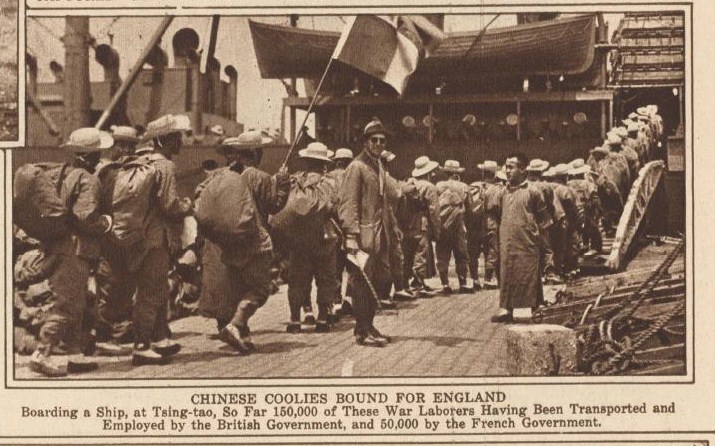

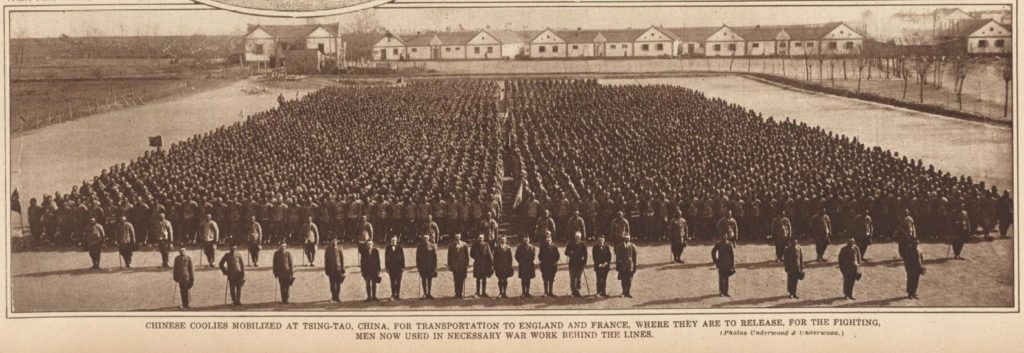

Fifty years after the Chinese Embassy led by Anson Burlingame a large number of Chinese were also headed to Europe. From The New-York Times September 22, 1918:

![Da qing guo shi ba sheng [quan tu]. (1900; Administrative map of Qing Dynasty.LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2002626767/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Qing-administrative-map-1900-277x300.jpg)