I wished that I were the owner of every southern slave, that I might cast off the shackles from their limbs, and witness the rapture which would excite them in the first dance of their freedom.

– Thaddeus Stevens, 1837 [1]

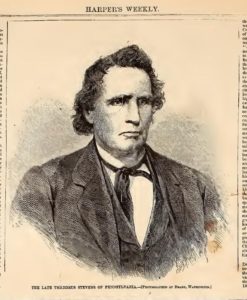

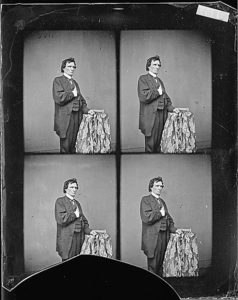

On August 11, 1868 Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, Radical Republican from Pennsylvania, died after at least several months of deteriorating health. As Chairman of the House Reconstruction Committee his last major effort was to help persuade the full House to impeach President Andrew Johnson. Mr. Stevens was one of the seven managers of the House prosecution before the U.S. Senate, but he was too sick to take much of a role in that impeachment trial.

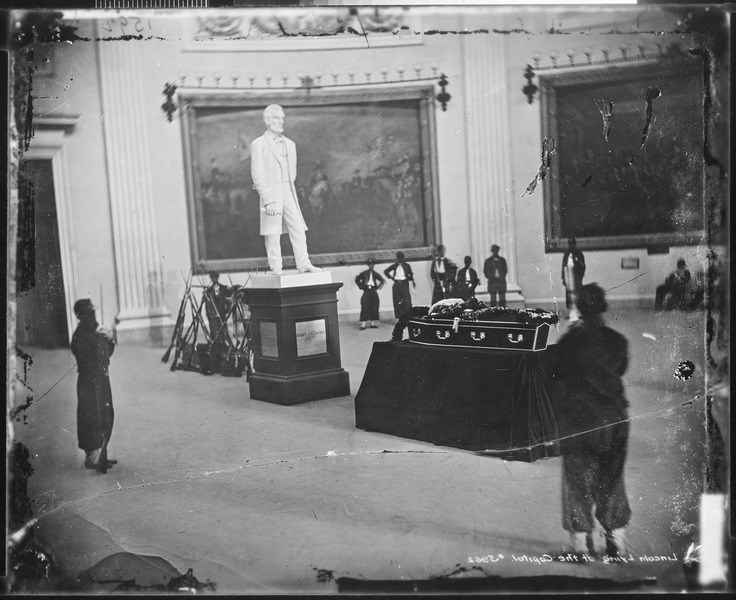

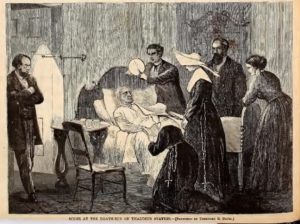

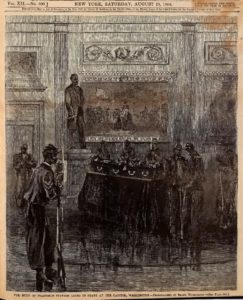

The August 29, 1868 issue of Harper’s Weekly (Harper’s pages 546, 548-549 at at the Internet Archives) provided a good deal of coverage of Mr. Stevens’ death and life. The journal began its editorial-like obituary by saying that even Democratic newspapers recognized his sincerity and independence; Republicans “praised his love of liberty,” but realized he lacked the qualities of “a true statesman and leader of men.” On his deathbed he ordered that two “colored” clergymen be admitted to pray with him. On August 13th five colored and three white pall-bearers carried his casket to the Rotunda of the Capitol near a life-sized statue of Abraham Lincoln. “The guard of honor were the officers of the Butler Zouaves, a colored military organization of Washington. The body thus lying in state was viewed by five or six thousand persons – white and black.”

An editorial in The New-York Times on August 13, 1868 saw the Republican Party as practical vehicle for Thadddeus Stevens to promote his strong anti-slavery beliefs; he was effective during the war but less so during Reconstruction :

Thaddeus Stevens.

The death of Mr. THADDEUS STEVENS deprives the Radical section of the Republican Party of it recognized leader, and the House of Representatives of its most conspicuous, and, in some respects, most influential member.

From the first an ardent politician, Mr. STEVENS was not always an extreme one. His earliest experiences in Congress were as an associate of representative Whigs, and the foundations of his after influence were laid deep in earnest, persistent work. It was a diligent committeeman, zealous, untiring and faithful in the performance of the duties intrusted to him – not as a glib and frequent speaker, or the devotee of hobbies – that Mr. STEVENS worked his way to prominent usefulness. He was, however, from conviction, an opponent of the slave system, and when the formation of the Republican Party furnished the means of organized and effective, because practical, resistance to the encroachments of the Southern oligarchy, he threw himself into the movement with the energy that characterized him in everything. The difficulties of the contest did not dishearten him. He saw in the Republican Party a pledge of emancipation from the evils which enthralled and degraded the Republic, and he contributed greatly to its success.

The rebellion developed exigencies and created opportunities which made the reputation of Mr. STEVENS national. … With the progress of the conflict came freer scope for his peculiar characteristics. He comprehended the magnitude of the crisis, while the majority about him saw but dimly its proportions, and realized the necessity of bold, strong measures, while others clung to hopes of pacification and compromise. He was one of the few who are not afraid to grasp first principles and lay hold of great truths, or to push them to their remotest logical result. Thus he differed with the Administration and the party as to the relation of the rebel States to the Union, and the course that should be pursued in regard to them. He discerned the expediency of emancipation, and urged it long before Mr. LINCOLN issued his proclamation.

Mr. STEVENS was not at that period the legislative dictator he afterward aspired to be. He never concealed his opinions and purposes, and never hesitated to do all that could be done to promote them. But though ahead of the Republican Party, he was a steady co-worker with it through all the stages of the war, sustaining its every measure, and rendering valuable assistance to the Government in the execution of its plans.

The requirements which grew out of the restoration of peace, found Mr. Stevens less qualified for efficient service. For the needs of bitter strife, none could be more fitted by habits of thought or readiness for rough and ready action. Means were less thought of than the results. And Mr. STEVENS, with his contempt for nice distinctions, constitutional or ethical, was just the man for the occasion. It was a season of perilous excitement, and the qualities of revolutionary leaders reappeared in him. He failed, as men cast in his mould usually do fail, when the time came for reconstructing the shattered institutions of the South, and restoring friendly relations between the sections. The partisan leader occupied the place of the statesman. He was for consummating a conquest – not for hastening reconciliation. He would have supplemented the horrors of war with banishment and confiscation. He demanded measures that would have rendered the union of North and South, except in the relation of conqueror and conquered. The remorseless logic which sustained war measures, insisted on postponing the return of peace. He had so fostered hatred of the nation’s enemies, that he refused, even in their helplessness, to extend the fraternal hand. In the abstract, perhaps, and in the light of his convictions, he was in this consistent. Certainly he was outspoken, fearless, and, in a certain sense, formidable. But his spirit was unchristian, and his measures were unjust and impolitic.

It can not be truthfully said that Mr. STEVENS exercised a happy influence over the Republican policy in the matter of Reconstruction. His most extreme views were not accepted by the party. He never obtained a hearing for his confiscation scheme, and the territorial doctrine on which he predicated his plans was denied recognition. The Constitutional Amendment, which was originally offered as a basis of restoration, was so regarded in spite of him. And the conditions of Reconstruction, stern and sweeping as they are, would have been still more severe had his plans prevailed. He desired, in truth, to delay rather than to hasten the return of the excluded States, and he would have kept them out till doomsday rather than tolerate conditions lacking what he deemed essential.

On the subject of Reconstruction, then, Mr. STEVENS must be considered the Evil Genius of the Republican Party. … [As Chairman of the House Reconstruction Committee he had an “intolerant spirit” and was “defiant, despotic, and in all things irritation.” …]

His leadership entailed disaster in other directions. The impeachment was, perhaps, the most notable of his mistakes. Of that he was the promoter and guiding spirit. To him it owed its origin, and to his management the prosecution was indebted for whatever strength it possessed. Latterly his control of the House was evidently impaired. His feeble health gradually unfitted him for stormy contests, and the Republican Party seemed to feel the necessity of a cooler judgment and a more generous spirit in the conduct of its counsels. The Chicago Convention marked the triumph of other purposes than those which he had made his own, and foreshadowed a more generous and more judicious policy than that which he had favored.

According to the August 18, 1868 issue of The New-York Times many people visited the bodily remains of Thaddeus Stevens at his home in Lancaster, Pennsylvania on August 15th and 16th. On the morning of the 17th the casket was opened one last time for the crowd: “The coffin was decorated with wreaths, and a cross of evergreen and white lillies. The face was becoming somewhat discolored, but the expression was the same, and all who had known him agreed that the appearance was more natural than they bad expected.” Later that day about 15,000 people attended his burial ceremonies.

As Eric Foner has written, “For one last time, Stevens challenged his countrymen to rise above their prejudices, for he was buried in an integrated Pennsylvania cemetery, in order, according to the epitaph he had composed, ‘to illustrate in my death the principles which I advocated through a long life, Equality of Man before his Creator.'”[2]

You can still find the grave in Lancaster. The complete inscription on his tombstone:

I repose in this quiet and secluded spot,

Not from any natural preference for solitude

But, finding other Cemeteries limited as to Race

by Charter Rules,

I have chosen this that I might illustrate in my death

The Principles which I advocated through a long life:

EQUALITY OF MAN BEFORE HIS CREATOR.

According to William S. McFeeley, on one occasion Thaddeus Stevens tempered his belief in the equality of man for what he thought was political expediency. In 1866 Radicals held a convention in Philadelphia to counter a conservative National Union convention. Mr. Stevens urged radicals in Rochester, New York not to send Frederick Douglass as a delegate to the convention because radical Congressmen attending the convention were afraid that their white constituents would vote against them in the fall elections if they even appeared to support full political and social equality for black men. Frederick Douglass as delegate might get voters thinking that way. Rochester sent Douglass anyway. Despite pleas from Stevens and others Mr. Douglass attended the convention anyway, walking to Independence Hall arm-in-arm with a white man. Theodore Tilton. “Stevens regarded the gesture as ‘foolish bravado.'” The only famous attendee who warmly greeted the pair was “bluff, irrepressible (and totally unembarrassable) Benjamin Butler.”[3]

Civil War Talk discusses the photo of the Butler Zouaves guarding the remains of Thaddeus Stevens at the Capitol Rotunda

The image that accompanies a biography at the National Endowment for the Humanities shows Thaddeus Stevens in boxing gloves.

The photo of Mr. Stevens’ casket at the Capitol Rotunda comes from Wikipedia. The three brown-backed drawings were published in the August 29, 1868 issue of Harper’s Weekly at the Internet Archives. From the National Archives: times four, managers. From the Library of Congress: tomb, cartoon

- [1]Statement at the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention (July 1837), quoted in Thaddeus Stevens, Scourge of the South (1959) by Fawn M. Brodie, p. 63 at Wikiquote↩

- [2]Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: HarperPerennial, 2014. Updated Edition. Print. page 344.↩

- [3]McFeely, William S. Frederick Douglass. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1991. Print. page 250-251.↩

![The Radical Party on a heavy grade / J.M. Ives, del. ; on stone by Cameron ([New York : Currier & Ives], c1868. ; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2003674599/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/04990v-1024x806.jpg)