Almost eight years ago the American Civil War sesquicentennial commemoration was warming up as some blogs looked at the 1860 presidential campaign. Those remembrances of past events really got serious with the election of Abraham Lincoln. It was still over five month until the bombing of Fort Sumter and even four months until Mr. Lincoln would be inaugurated, but a lot was happening. During that time lame-duck President James Buchanan vacillated as seven southern states seceded from the Union and as Jefferson Davis was sworn in as the president of the Confederate States of America in Montgomery, Alabama. On March 4, 1861 Mr. Lincoln took over.

On June 1, 1868 James Buchanan died at home.

From Harper’s Weekly June 20, 1868:

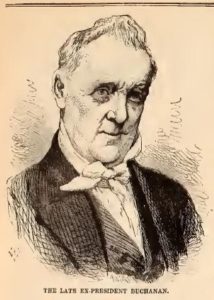

EX-PRESIDENT BUCHANAN.

JAMES BUCHANAN, fifteenth President of the United States, died at Wheatland, Pennsylvania, on June 1, 1868, aged seventy-seven. we give above an accurate portrait of the deceased ex-President.

Mr. BUCHANAN was born at Stony Batter, Franklin County, Pennsylvania, on April 22, 1791. His parents were of Scotch-Irish extraction. He was graduated at Dickinson College in 1809, and admitted to the Lancaster bar in 1812. At 23 he entered the Pennsylvania Legislature, and at 29 was elected to Congress to represent the district now represented by THADDEUS STEVENS. At 41 he was appointed Minister Plenipotentiary to Russia, and on his return, in 1834, was elected to the United States Senate. He remained in the Senate until the beginning of Mr. POLK’S administration, during which he held the position of Secretary of State, afterward retiring to private life. On the accession of Mr. PIERCE to the Presidency, Mr. BUCHANAN was appointed Minister to England, from which post he returned to the United States to become the candidate of the Democratic party for the Presidency. During his administration the log-plotted rebellion was greatly hastened. Mr. BUCHANAN took no steps to prevent it, and during its brief but violence existence he looked on calmly from his place of retirement. This is perhaps the harshest criticism which can be passed on Mr. BUCHANAN – harsh enough in all reason. Undoubtedly his weakness in not dealing summarily with the traitors while they were plotting at Washington gave great strength to the rebellion, and his evident desire to end his administration peacefully, no matter in what condition he left the government to his successor, must naturally ever be a reproach to his memory. Yet his services previous to his Presidential career were valuable, particularly those abroad, and in all charity we should remember these, and endeavor to forget the rest.

In an article from about 50 years ago about the fifteenth president Michael Harwood saw James Buchanan as

the last in a string of Presidents, Northern men with Southern principles or vice versa, who stood for compromise between two bitterly opposed groups of radicals; the last in a line chosen because, it was thought, they would not press for a nation-splitting decision on the slavery issue. During their service, the situation had grown more dangerous despite continued legal and political compromises. Pierce had been broken by it. Now it was Buchanan’s turn.

After Abraham Lincoln was elected, President Buchanan “tried to remain in the middle” until a peaceful solution could be worked out. He didn’t think he had the legal right to do much and only had a few hundred federal troops at his disposal. He thought that “the best solution lay in a clarifying amendment to the Constitution that would guarantee slavery in the states that wanted it,” but that idea got nowhere. He saw himself as a “breakwater between North and South, both surging with all their force against me.” After Lincoln’s inauguration Buchanan “was made the scapegoat for the havoc that followed.”

His failure to act at once in November to cut off secession was also criticized – justly, if one also gives him credit for for seeking to maintain not just the Union, but his idea of constitutional government as well. …

Although Mr. Buchanan supported the war after the rebels bombed and took over Fort Sumter, President Lincoln and others attacked him for letting the Union fall apart.

“It is one of those great national prosecutions,” wrote Buchanan himself before he died in 1868, “… necessary to vindicate the character of the Government. …” The world, he said, had “forgotten the circumstances” and blamed his “supineness.”

… The conciliating James Buchanan reaped a whirlwind that had been decades in the making. His administration was a failure, yet in many aspects it was less his administration than that of the “irrepressible conflict.” [1]

President Buchanan’s conciliation doesn’t seem too outrageous given that the original Constitution was in part a sectional compromise, but, as Michael Harwood indicated, the “irrepressible” can couldn’t get get kicked down the road any longer.

I’d take this with a grain of salt given my age and eyesight, but it seems that on the front page of the June 4, 1868 issue of The New-York Times, in addition to orders by President Johnson and General Grant to honor the ex-president’s memory, Secretary of the Treasury Hugh McCulloch published an order announcing the death of Mr. Buchanan and directing all ships in the Revenue Marine to fly their flags at half-staff the day after the order was received. Harriet Lane (later Johnston), James Buchanan’s niece, served as the bachelor president’s First Lady. After the war began a revenue cutter named in her honor was converted to a Union navy ship. That ship was captured by the Confederates during the January 1, 1863 Battle of Galveston

Trying to make sure I had the phrase right in English, I found some unexpected (to me) Latin: De mortuis nil nisi bonum dicendum est – “Of the dead nothing but good is to be said”

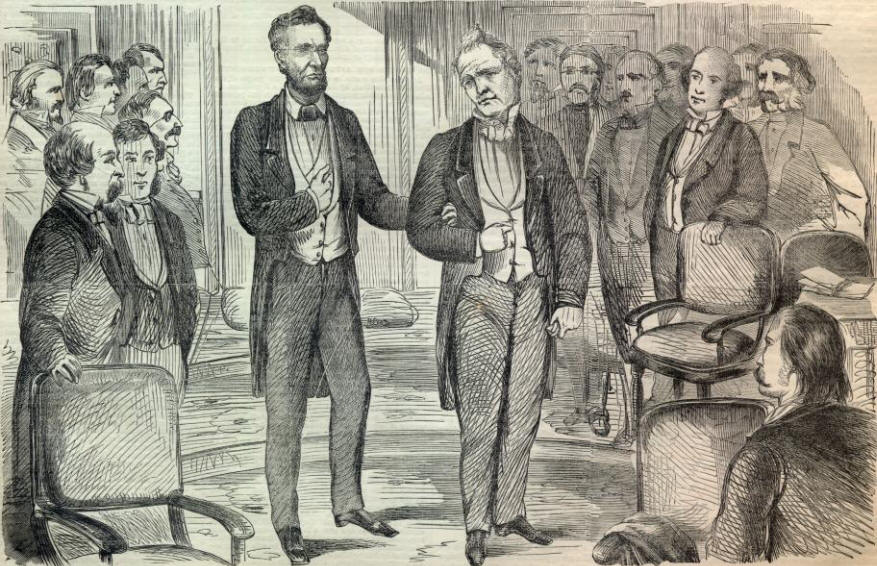

The Harper’s obituary is located at the Internet Archives. The image of the two presidents was originally published in the March 16, 1861 issue of Harper’s Weekly – you can see it and the whole issue at Son of the South. A couple portraits come from a two volume biography at Project Gutenberg – a young buck, statesman. The image of the rebels capturing the Harriet Lane can be found at the U.S. Navy. Harriet Lane Johnston donated land to the state of Pennsylvania that would become Buchanan’s Birthplace State Park. Clint’s photo of the pyramid marking the president’s birthplace is licensed by Creative Commons From the Library of Congress: daguerreotype; cartoon – hands up; Harriet flesh and blood, statue; on Broadway The photo of the president as an old man is from Wikipedia.

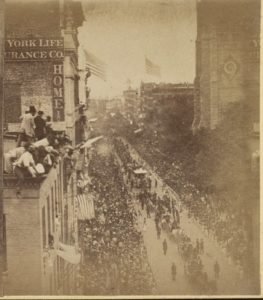

The picture of Mr. Buchanan welcoming the Japanese Embassy was reproduced in the American Heritage book of presidents. I found that image (from the May 26, 1860 issue of Harper’s Weekly) and the cartoon (from the June 2, 1860 issue of Harper’s Weekly) at the HathiTrust. After Washington the embassy traveled to New York City.

I noticed that sign for New York Life in the Broadway photo. According to Wikipedia the early history of the company seems related to the “irrepresible conflict”:

In its early years (1846–1848) the company insured the lives of slaves for their owners. The board of trustees voted to end the sale of insurance policies on slaves in 1848. The company also sold policies to soldiers and civilians involved in combat during the American Civil War and paid claims under a flag of truce during that time. In the late 1800s, the company began employing female agents.

___________________________________________________________

- [1]Harwood, Michael. “James Buchanan” The American Heritage Pictorial History of the Presidents of the United States Volume 1. Editor in Charge Kenneth W. Leish. American Heritage Publishing Co. Inc., 1968. Print. pages 361, 368.↩

![South Carolina's "ultimatum" ([New York] : Published by Currier & Ives, 152 Nassau St. N.Y., [1861] ; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2003674566/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/05027v.jpg)

![James Buchanan, half-length portrait, three-quarters to the left] (between 1844 and 1860; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2004663893/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/3c10150v-150x150.jpg)

![Harriet Lane Johnston [inaugural dress from First Ladies Collection, 9/3/24] (LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2016838342/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/12073v-242x300.jpg)