Spiro Agnew must have seemed like a godsend to our high school Latin teacher. When Vice-president Agnew got into some difficulties with the law in 1973 he eventually resigned from office after pleading no contest, or in Latin nolo contendere, “I do not wish to contend.” Our teacher let us know that here was Latin in a major news story, Latin being actually and directly used in modern American life. At least modern America at the time – it’s hard to believe, but it’s going on two score and five years since the plea.

Our teacher would have told us that in general Latin was relevant to law and the legal profession, so it’s not surprising that Latin was evident in a very special legal proceeding even longer ago. On May 16, 1868 the United States Senate failed to convict President Andrew Johnson on the 11th Article of Impeachment by just one vote. The impeachment court adjourned for ten days as many Republican legislators attended the Republican National Convention and voted for Ulysses S. Grant as nominee for president. On May 26th the trial reconvened in the Senate chamber. Votes were taken on Impeachment Articles three and four – in each case the Senate again failed to convict by a single vote. Even though there were still eight other articles, the Secourt adjourned sine dies – without any day set for the proceedings to resume. The practical effect was that the trial was over, Andrew Johnson was acquitted, and, as it turned out, would serve out the rest of Abraham Lincoln’s second term.

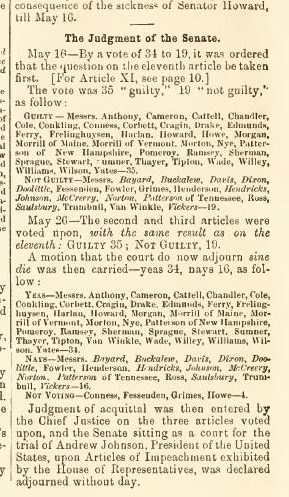

In his 1871 The Political History of the United States of America During the Period of Reconstruction, (from April 15, 1865, to July 15, 1870,) (at the Internet Archive page 282) Edward McPherson succinctly summarized the four votes: