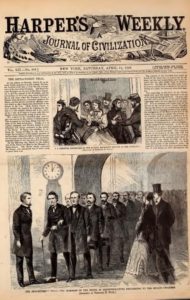

On March 23, 1868 President Andrew Johnson’s defense lawyers answered impeachment charges in the United States Senate – the trial court. The next day “the replication of the House was filed by the Managers of Impeachment. The House simply reasserted the charges, and announced that it stood ready to prove them true. … [on March 30th] the trial really began in earnest, and has been continued to the present writing in a quiet, but intensely interesting manner.” [from the April 11, 1868 issue of Harper’s Weekly – see image to the left]

As Hans L. Trefousse wrote, spectators weren’t expecting the first day to be quiet:

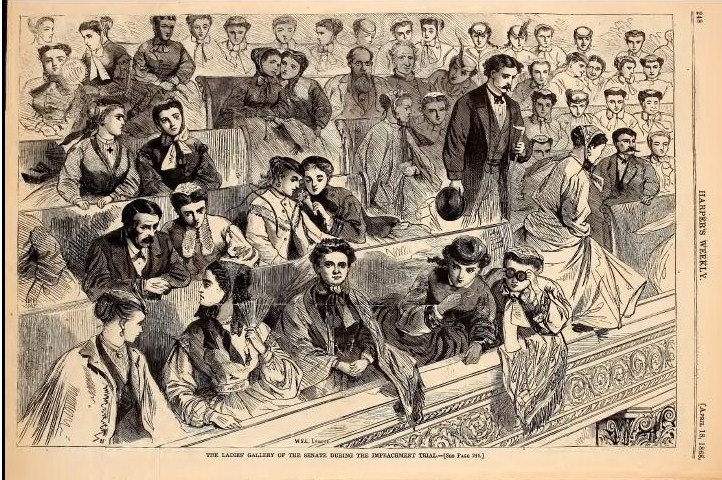

When proceedings opened on March 30, 1868, another large crowd had assembled on Capitol Hill. Ben Butler was to make the opening argument; his histrionics were notorious, and the audience undoubtedly was hoping to be entertained. The newspapers remarked upon the brilliant appearance of the Senate galleries: ladies in their finery, foreign diplomats, distinguished guests – all were there. At 12:30 Chief justice Chase took his chair. The defense entered. Then came the House of representatives, led by Stevens and Bingham arm in arm. When Butler, with a pile of manuscripts before him, standing with his back to the chief justice and facing the Senate, began to speak, all were expectant.

At first they were disappointed. A long, dry legal argument against the contention that the high crimes and misdemeanors for which the president could be impeached had to be statutory crimes was not very interesting. Nor did the attempt to deny Johnson’s right to test the constitutionality of a law or the theory that the Senate was not a real court of law bound by ordinary rules of evidence cause much excitement. Butler sought to prove not only that Stanton, though appointed by Lincoln, was covered by the Tenure of Office Act, but that the appointment of Thomas, as charged in the first eight articles, was a serious offense. Only toward the end of his plea, when he reached the tenth article, his own, did Butler live up to his reputation. “By murder most foul,” he thundered in his attack upon the president, “did he succeed to the Presidency and is the elect of an assassin to that high office, and not of the people.” It was not very dignified, but as expected, radical journals praised his performance, while the opposition thought it was below par.[1]

Thanks to the Library of Congress you can read all of Mr. Butler’s opening argument as reported in the Congressional Globe. I didn’t read too much of it, but I did cut out the last part of Benjamin Butler’s discourse on his Article 10, which was aimed at all the egregious things Andrew Johnson uttered during his 1866 Swing Around the Circle.

- [1]Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1997. Print. pages 318-319.↩