150 years ago a northern periodical thought that the United States Congress would probably eventually impeach and convict Andrew Johnson, but it was worried that the president was conspiring to ignore that result as he had been ignoring the will of Congress right along. The best countermeasure would be for voters to support the Republican party in the elections of 1867. Here’s the beginning and the end of about a 3500 word article from the the November 1867 issue of The Atlantic Monthly (pages 633-638):

THE CONSPIRACY AT WASHINGTON.

The people of the United States now have the mortification of standing before the world in the attitude of a swindled democracy. Their collective will is crossed by the will of one individual, whose only title to such autocracy is in the fact that he has cheated and betrayed those who elected him. There might be some little compensation for this outrage, if the man himself possessed any of those commanding qualities of mind and disposition which ordinarily distinguish usurpers; but it is the peculiarity of Mr. Johnson that the indignation excited by his claims is only equalled by the contempt excited by his character. He is despised even by those he benefits, and his nominal supporters feel ashamed of the trickster and apostate, while condescending to reap the advantages of his faithlessness. No party in the South or in the North thinks of selecting him as its candidate, for the vices and weaknesses which make an excellent accomplice and tool are not those which any party would consider desirable in a leader. Whatever office-seekers, partisans, traitors, and public enemies may find in Mr. Johnson, it is certain that they find in him nothing to respect. He is cursed with that form of moral disease which sometimes renders a man ridiculous, sometimes infamous, but which never renders him respectable,—namely, vanity of will. Other men may be vain of their talents and accomplishments, but he is vain of the personal pronoun itself, utterly regardless of what it covers and includes. Reason, conscience, understanding, have no impersonality to him. When he uses the words, he uses them as synonymes of his determinations, or as decorative terms into which it pleases him to translate the rough vernacular of his wilfulness and caprices. The “Constitution,” also, a word constantly profaned by his lips, is not so much, as he uses it, the Constitution of the United States as the moral and mental constitution of Andrew Johnson, which, in his view, is the one primary fact to which all other facts must be subordinate. His gross inconsistencies of opinion and policy, his shameless betrayal of his party, his incapacity to hold himself to his word, his hatred of a cause the moment its defenders cease to flatter him, his habit of administering laws he has vetoed, on the principle that they do not mean what he vetoed them for meaning, his delight in little tricks of low cunning,—in short, all the immoral and unreasonable acts of his administration have their central source in a passionate sense of self-importance, inflaming a mind of extremely limited capacity.

Such a person, whose mere presence in the executive chair of a constitutional country is itself “a high crime and misdemeanor,” is of course the natural prey of demagogues, and he now appears to be surrounded by demagogues of the most desperate class. His advisers are conspirators, and they have so wrought on his vulgar and malignant nature that the question of his impeachment has now come to be merged in the more momentous question whether he will submit to be impeached. Constitutionally, there is no limit to the power of Congress in this respect but that which Congress may itself impose. The power is plain, and there can be no revision of the judgment of the Senate by any other power in the government. But Mr. Johnson thinks, or says he thinks, that Congress itself, as at present constituted, is unconstitutional. He believes, or says he believes, that the defeated Rebel States whose representatives Congress now excludes are as much States in the Union, and as much entitled to representation, as New York or Ohio. As he specially represents the defeated Rebel States, it is hardly to be supposed that he will consent to be punished for crimes committed in their behalf by a Congress from which their representatives are excluded; and it is also to be presumed that the measures he is now taking to obstruct the operation of the laws of Congress relating to reconstruction are but preliminary to a design to resist Congress itself. …

… Now, if by apathy on the part of Republicans and audacity on the part of Democrats the autumn elections result unfavorably, it will then be universally seen how true was Senator Sumner’s remark made in January last, that “Andrew Johnson, who came to supreme power by a bloody accident, has become the successor of Jefferson Davis in the spirit by which he is governed, and in the mischief he is inflicting on the country”; that “the President of the Rebellion is revived in the President of the United States.” What this man now proposes to do has been impressively stated by Senator Thayer of Nebraska, in a public address at Cincinnati: “I declare,” he said, “upon my responsibility as a Senator of the United States, that to-day Andrew Johnson meditates and designs forcible resistance to the authority of Congress. I make this statement deliberately, having received it from an unquestioned and unquestionable authority.” It would seem that this authority could be none other than the authority of the Acting Secretary of War and General of the Army of the United States, who, reticent as he is, does not pretend to withhold his opinion that the country is in imminent peril, and in peril from the action of the President. But it is by some considered a sufficient reply to such statements, that, if Mr. Johnson should overturn the legislative department of the government, there would be an uprising of the people which would soon sweep him and his supporters from the face of the earth. This may be very true, but we should prefer a less Mexican manner of ascertaining public sentiment. Without leaving their peaceful occupations, the people can do by their votes all that it is proposed they shall do by their muskets. It is hardly necessary that a million or half a million of men should go to Washington to speak their mind to Mr. Johnson, when a ballot-box close at hand will save them the expense and trouble. It will, indeed, be infinitely disgraceful to the nation if Mr. Johnson dares to put his purpose into act, for his courage to violate his own duty will come from the neglect of the people to perform theirs. Let the great uprising of the citizens of the Republic be at the polls this autumn, and there will be no need of a fight in the winter. The House of Representatives, which has the sole power of impeachment, will in all probability impeach the President. The Senate, which has the sole power to try impeachments, will in all probability find him guilty, by the requisite two thirds of its members, of the charges preferred by the House. And he himself, cowed by the popular verdict against his contemplated crime, and hopeless of escaping from the punishment of past delinquencies by a new act of treason, will submit to be removed from the office he has too long been allowed to dishonor.

I haven’t seen any documentation that Nebraska senator John Milton Thayer got his information about President Johnson planning to forcibly ignore Congress from General Grant. According to Wikipedia John Thayer did serve in the Union army in the western theater throughout the Civil War. President Grant appointed him as territorial governor of Wyoming in 1875.

As it turned out President Johnson got “a tremendous boost” from the results of the fall elections. “Always convinced that in the long run the people would sustain him, he thought that the Democratic gains in state after state were the justification for which he had been waiting.” [1] According to The New-York Times President Johnson was serenaded by between four and five thousand people in front of the White House on the evening of November 13, 1867. The Conservative Army and Navy Union seems to have organized the event, invited “all Conservatives and Democrats” to participate, and led the procession from its headquarters to the White House. The audience was reportedly disappointed that the president didn’t make a longer address. “… he read a few remarks from carefully prepared manuscript. [sic]” He was gratified by the fall election results. The president expressed his confidence that the people by their votes would help preserve the Constitution and save the Republic. He was “hopeful that in the end the rod of despotism will be broken, the armed heel of power lifted from the necks of the people, and the principles of a violated Constitution preserved.”

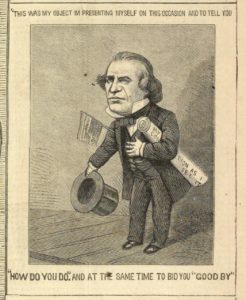

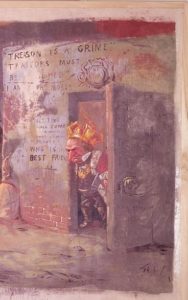

You can see the photo of John Milton Thayer at the Library of Congress. Also at the Library the two works by Thomas Nast: His Own Constitution from Andy’s Trip and King Andy from The massacre at New Orleans

- [1]Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1997. Print. pages 298-299.↩