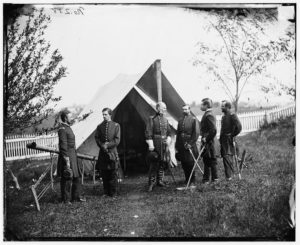

Seneca County (New York) Historian Walt Gable’s new book came out in July of this year. As I started leafing through the pages of Historic Tales of Seneca County, New York I stopped when I noticed what might possibly be a photograph of a Civil War soldier. Sure enough, the soldier was General Marsena Rudolph Patrick, who served as Provost-Marshal of the Union Army of the Potomac from October 1862 until the end of the war. One of his tasks as Provost-Marshal was to try to discourage gambling in the army. Because of the Civil War connection, I sort of naturally made General Patrick’s tale the first one of Walt’s I read.

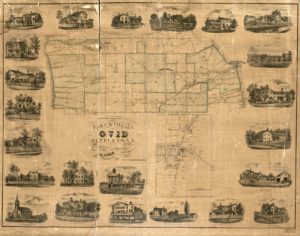

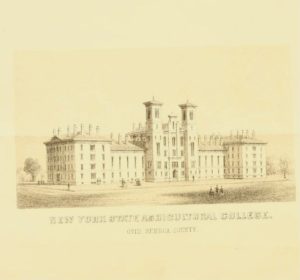

During the 1840’s The New York State Agricultural Society began to promote the idea of agricultural schools, which following a European lead, would “train farmers to make better use of the new farming methods and technology developing as part of the Industrial Revolution.” By the late 1850’s an agricultural college had been chartered and a 600 acre site chosen in the Seneca County towns of Ovid and Romulus. Marsena Patrick was chosen as the institution’s president. The college opened on December 5, 1860. For $200 a year students would receive “classroom instruction and on-the-farm experience”.[1]

In 1859 the Agricultural College published its Charter Ordinances, Regulations and Course of Studies. Prospective students had to be at least sixteen years old and were directed how to apply: “Students, contemplating joining the institution, will be furnished with every necessary information by applying, personally or by letter, to M. R. Patrick, President of the College, Ovid, Seneca county, N. Y.”

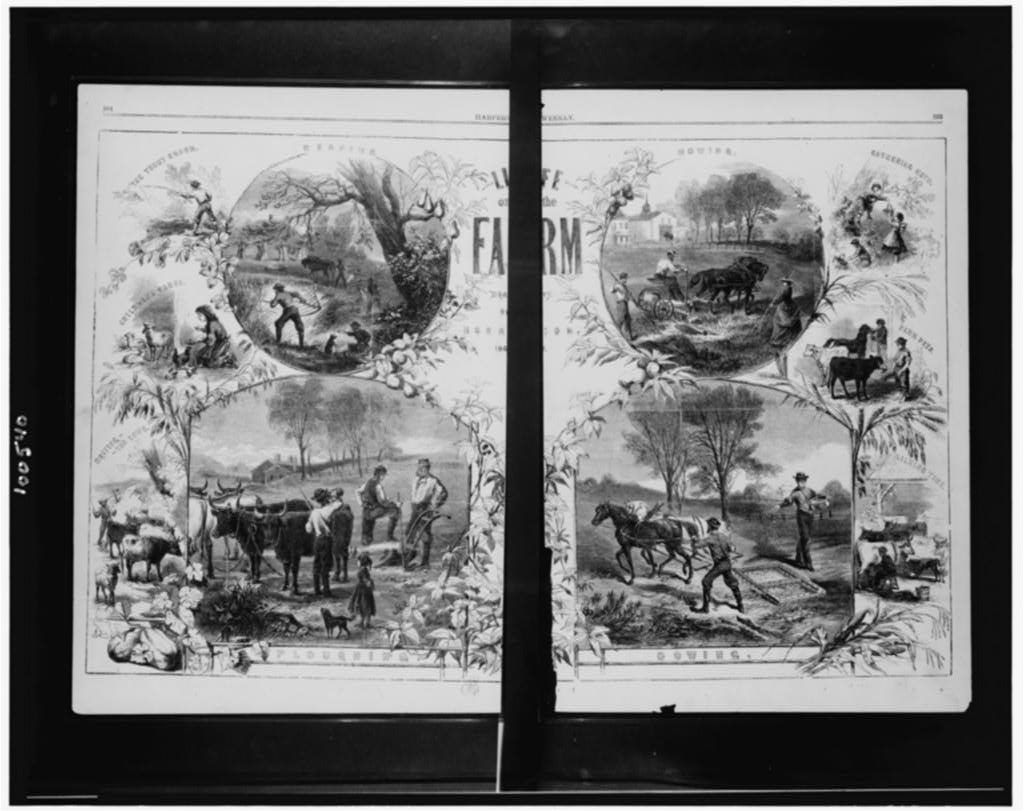

In addition to the rules and some historical background, the document detailed the college farm’s wide variety of soils, which would help students practice in different conditions. The course of study was a three-year program divided into summer and winter terms. The college was “not intended to be a manual labor school“, but each term included classroom studies and hands-on experience. Students would study everything from Algebra to Veterinary Practice and Vegetable Physiology and would practice a wide variety of skills, including plowing, planting and reaping, fence-making, irrigation, topographical map-making, animal husbandry, dairy management, and “making and preserving manures”.

___________________

Although never involved with animal husbandry, I thought I had a pretty good idea of how manure was made. Also, growing up in a rural area I sort of assumed that manure’s natural fertilizing qualities had always been common knowledge. I was wrong. According to A Short History of New York State, specifically a chapter entitled “The Rise of the Dairy State, 1825-1860”,[2] most New York farmers didn’t worry too much about fertilizers in the first part of the nineteenth century. However, knowledge of good farm practices, including the use of fertilizers, began to spread during that time. Simultaneously the supply of manure greatly increased. A transportation revolution accompanying the Industrial Revolution Walt mentioned dramatically changed state agriculture:

The expanding network of turnpikes, canals, railroads, and plank roads unleashed two revolutionary forces in New York agricultural history – the “pull” of the growing urban market and the pressure of western competition. The farm family of 1860 was spending an increasing amount of its time producing goods for a distant market and less for its its immediate use than it had in pioneer days, and it became more dependent upon the storekeeper for goods. By 1860 practically all farm women purchased cotton and wool goods instead of making them at home. [3]

Farmers adjusted to market price fluctuations and crop pests and disease by changing what they produced.

The rise of the dairy industry was by far the most significant development in the agricultural history of the state between 1825 and 1860 [dairy replaced wheat in value by 1850]. Farmers discovered that cows were their most reliable money-makers, since both the domestic and foreign market kept demanding more dairy products. Dairying had several advantages. Manure helped restore soil fertility, and butter-making and milking utilized the labor of women and children, which the decline of home manufacture of cloth had released. Farmers found it easy to store cheese and butter and to carry them to market.[4]

“Butter was the backbone of the dairy industry…” Cheese factories were developed; railroads allowed country milk to be shipped to New York City. Although, “Farm management practices of the ordinary farmer continued to be soil-depleting and slovenly,” agricultural knowledge began to spread. “In 1834 [Jesse] Buel founded the Cultivator, a journal which preached the benefits of scientific agriculture. His own profitable experience added weight to his arguments for manuring, draining, deep plowing, crop alternation, and the substitution of fallow crops for naked fallows.” [5]

Other farm journals began to circulate; in 1832 the New York State Agricultural Society was established. County fairs and a state fair started being held. More formal education was also promoted by Buel and others. During the 1850’s momentum was generated for a state agricultural college. The college in Ovid was founded with Marsena Patrick as president, but it “failed to survive.” [6]

As Walt writes, “[t]he timing for the opening of this college was bad.” [7] A timeline: On November 6, 1860 Abraham Lincoln was elected United State president. The agricultural college opened on December 5th. On December 20th South Carolina became the first in a succession of southern states to secede from the Union.

After the bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12-13, 1861 New York State Governor Edwin Morgan called West Point graduate Marsena Patrick to the state capital in Albany and charged him with developing a system to enlist and train volunteers. But it wasn’t just the college president who went to war. “By May, so many of the approximately forty students had left to fight that the college closed for the summer.” It never reopened. Cornell University became the state’s land grant college in 1865. In October 1869 the Willard Asylum for the Insane began admitting patients on the site of the closed college in Ovid. Currently that site houses the Willard Drug Treatment Campus.[8]

Unlike his agricultural college, Marsena Patrick survived the war. He served as president of the New York State Agricultural Society from 1867-1868. On February 14, 1868 The New-York Times reported on the Agricultural Society’s annual meeting, including a speech by its president:

… At the evening session, held in the capitol, Gen. PATRICK delivered an address to the farmers. He spoke of the loss and denudation of our forests, becoming in danger of being lost by the constant movement of the ax, and thought that legislative interposition should be invoked for their protection. The civil war had produced great effects in many of the pursuits in agriculture, and in one, since the war, there had been almost a total change. That was in the cheese factories, where by combined efforts they had been able to do much more than before. There were other changes, some engendered by the war and some by other causes. He was sorry to see, as he sometimes did see, a great, stout, manly-looking fellow, peddling books, essences or jewelry. It was only done because labor was not honored, because labor had been cast down. We should elevate it. Let us bear in mind the relations we owe to our country and to our liberty, and that society is based on agriculture, the most ancient of professions. Yet, with its age, new ideas come up. The great rapidity with which transportation could be obtained had changed many branches of farming; fish culture had been introduced, and the dairy was now much more important than before. It gave him pleasure to assure the Society that the disease known as rinderpost had entirely ceased as an epidemic, excepting in South Holland. …

Two good web articles tell of General Patrick’s Civil War experiences and challenges: Civil War Stories of Inspiration and Civil War Bummer. The Bummer piece mentions that after the war Patrick was soon relieved of his command of the District of Henrico in Richmond because General Grant thought he was too kind of heart for the job. Bummer also fills out the story of Marsena Patrick’s life after serving as the Agricultural Society’s president:

He then spent the next two years as a state commissioner. He became a widely known public speaker, particularly on topics related to technological advances in agriculture. Patrick showed a true interest in the care of former soldiers and moved to Ohio, becoming the governor of the central branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. Patrick died on July 27, 1888 at the age of 77 in Dayton, Ohio, and was buried in the Dayton National Cemetery.

You can find the General Patrick’s grave (as well as the photo used in Walt’s book) here.

______________________________________

______________________________________

From a Blue-Gray perspective Walt Gable rounded out the story of the agricultural college’s demise and it’s replacement with the insane asylum in a newspaper article in July. Walt wrote about several Seneca County sites that honor Civil War veterans. I never knew that “More than 150 Civil War veterans who were patients of the Willard Asylum for the Insane (renamed the Willard State Hospital in 1890) are buried in the northwest section of the facility’s cemetery, nearest to Seneca Lake.” I was inspired to take Walt’s suggestion to visit.

The first thing I noticed walking up the hill into the cemetery was that only the Civil War veteran section had gravestones (except for a couple anomalies in the rest of the burying ground; there was a gravestone for Angeline Billings Loos, 1868-1900). And there was even more of a sense of segregation about the place. The left side was mowed and included the veterans and an Old Jewish section. The right side was in the rough and was divided into old and new Protestant, old and new Catholic, and new Jewish. Probably because the Old Jewish section was mowed, I could more easily make out the small, circular, ground-level grave identifiers – see 37 below.

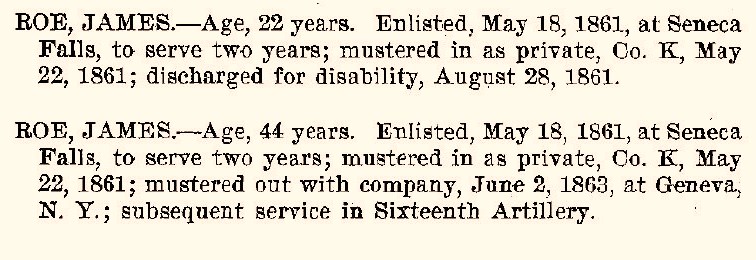

The Civil War veterans came from all over, but I did notice a few representatives from the local 148th and 333rd regiments, as well as one from the 50th NY Engineers. An example below is JAS ROE CO. K. 33 N.Y. INF. Several of the markers had aged enough to be unreadable (at least to me). In his article Walt mentioned that prior county historian Betty Auten learned that one of the graves belonged to William Collins, who was part of the squad that helped capture John Wilkes Booth. I didn’t notice that grave, possibly because it had aged too much.

from the 33rd’s roster

The image of the college and all the other brownish cut-outs come from agricultural college’s Charter Ordinances, Regulations and Course of Studies at Hathitrust. From the Library of Congress: General Patrick on horseback; map; farm overlooking Cayuga Lake, part of which borders Ovid on the east; changes, which skips ahead about fifty years to the July 25, 1906 issue of Puck; general with staff; peddler from the June 20, 1868 issue of Harper’s Weekly; a little less than a year earlier the August 20, 1867 issue of Harper’s Weekly published farm life. The images of the grain cradle and McCormick reaper come from Agricultural Implements and Machines

in the Collection of the National Museum of History and Technology by John T. Schlebecker at Project Gutenberg – apparently the Smithsonian has a grain cradle from about 1844 and a model of a McCormick reaper from 1831 in its collection. I visited Ovid and the Willard cemetery in August 2017.

What Marsena Patrick would think of robots? His speech to the agricultural society reminded me of some of the tensions of our times. The general had intended to work as president of a college dedicated to applying science and technology to agriculture to make it more productive with presumably less of an emphasis on manual labor, yet he could bemoan big strong men selling jewelry. I certainly can relate. I remember a co-worker suggesting I take a Windows 95 course and being totally amused by difficulty controlling a mouse. Then years later when I finally got that mouse thing down folks started touching the screen … smudges all over and that’s a good thing, swiping left and right and all around … rubbing the thing like trying to get a genie out of the bottle … my big fingers flailing on the minuscule smartphone keyboard, yeah, please show the password I’m typing in because I have no idea. But change has been happening for a real long time. I believe I’ve heard that hunting/gathering is an even more ancient profession than farming and that agriculture’s greater surplusses allowed there to be a more professional priest class. That must have shaken up society.

I assumed that General Patrick was talking about technological change when he talked about men peddling, but that might not be true or it might have been only part of the story. From an article titled “FUGITIVES FROM LABOR” in the September 1867 issue of The Atlantic Monthly (pages 371-372):

… As a general rule, everybody is above his business, and thinks manual labor mean, and only fit for emigrants.

It is said that our mechanics are nearly all foreigners, and that an American apprentice is an extinct species, like the cave bear or the dodo. Farmers’ sons prefer any way of getting their bread to working with their hands. The pedler’s caste ranks higher than the manly independence of the plough. A country store is an object of ambition, where the only toil is to deal out a glass of wretched tipple to the village sots who haunt those castles of indolence to drink, to smoke, and to twaddle over stale village news. Some young fellows solicit subscriptions for maps or for great American works, or drum for fruit nurseries, patent clothes-wringers, or baby-jumpers. Others aspire to enter the religious mendicant orders of America as paid brethren. They are too proud to work, but not ashamed to beg. Beg is perhaps a hard word; but solicitation is begging when the solicitor personally profits by it.

The sons of trading fathers despise the old tiresome roads to wealth of their class. Ledgers and law-books are too slow. All are in search of the short cut to fortune. They believe in the philosopher’s stone as implicitly as the alchemists; they seek for it as earnestly. It is a jewel that will last forever, but its composition varies with each generation. …

But technology definitely does change life and some change sure seems good. From pages 274-275 the New York State history referenced in this post:

The influence of the urban market and the railroad is clearly illustrated in the growth of the milk industry. Before the construction of the railroads enabled farmers to send fresh country milk to market, a great deal of the milk drunk in New York City came from the immediate vicinity. An unusual source was so-called distillery milk, that is, milk from cows drinking the swill of distilleries. This milk was widely sold. The barns attached to the distilleries were incredibly dirty, since the cows never left their filthy pens. Their only food was the thirty to forty gallons of hot mash they drank each day. The diseased animals produced a “blue, watery, insipid, unhealthy secretion” whose food value was questionable. Sometimes the dairymen put in chalk, sugar, flour, molasses, starch, and coloring matter in order to conceal the water which they had added in generous amounts. Physicians kept up a running warfare against this milk, blaming it largely for the alarmingly high infant mortality. One out of two children failed to reach his fifth birthday. Little was done before the Civil War to clean up this source of malnutrition and disease. [Although, according to Wikipedia, “In May 1858, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper did a landmark exposé of the distillery-dairies of Manhattan and Brooklyn that marketed so-called swill milk …”]

Country milk gradually took command of the New York City market after railroads were built. …

________________________________________________________

- [1]Gable, Walter Historic Tales of Seneca County New York. Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2017. Print. pages 20-22.↩

- [2]Ellis, David M., James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman. A Short History of New York State. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1957. Print. page 271-279.↩

- [3]ibid. page 271.↩

- [4]ibid. page 273-274.↩

- [5]ibid. page 274-275.↩

- [6]ibid. page 275-276.↩

- [7]Gable, Walter Historic Tales of Seneca County New York. Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2017. Print. page 23.↩

- [8]ibid. page 23-24.↩