A week earlier President Andrew Johnson tried to get around the strictures of the Tenure of Office Act by asking the most radical member of his cabinet secretaries to resign. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton refused. On August 12, 1867 President Johnson followed the rules set out in the Tenure Act and suspended Mr. Stanton pending Senate approval when Congress reconvened. General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant was named acting Secretary of War in the interim.

Here’s some background from an 1896 book, The Struggle between President Johnson and Congress over Reconstruction by Charles Ernest Chadsey (pages 127-136):

In the preceding chapters we have traced step by step the development of the theory of reconstruction and the formulation of the reconstruction acts of the 39th and 40th Congresses. We have noticed the wide divergence between the ideas of Johnson and those of the Republican party, and have seen that the whole program was carried over the vetoes of the President by the overwhelming Republican majority. But the contest between the President and Congress, which had been embittered by so many personalities on both sides, did not come to an end with the passage of legislation which fully embodied the congressional theory, but continued until it culminated in a desperate effort of the Republican party to remove Johnson from the presidential chair.

The very conditions under which he assumed the presidential office rendered his position difficult, and made estrangement of the executive and legislative departments an easy matter. On the particular issue of reconstruction Lincoln and Congress were at variance; but the tragic nature of Lincoln’s death caused this matter to be forgotten in the overwhelming sense of the loss of the man who had safely guided the government through the most trying years of its history. But, for a Congress so extremely Northern and Republican, with antagonisms and prejudices which only fratricidal wars can create, to be compelled to work with a man not only a Southerner, but practically a Democrat, must of necessity bring about a crisis.

Moreover, the flourishing condition of the spoils system served to aggravate the antagonism between the two departments. History shows that, while selfish motives are always indignantly repudiated by politicians, they account for many of the more important political movements of the century. With the immense federal patronage at his disposal, Johnson realized that he had a powerful instrument of revenge at hand, and he did not hesitate to use it. At a time when every congressman was under the strongest pressure from his home constituency, inability to gratify the demands of the voracious office-seeker was indeed a cause for bitterness.

We can thus easily distinguish three causes which, working together upon a strongly Republican Congress, resulted in the attempted removal of the President. First, the antagonism arising from different fundamental political ideas, the strained conditions of the times, and the woeful tactlessness of Johnson; second, the almost morbid yet natural fears of the Republican party regarding the sometime seceded States; third, the anger aroused by the use of federal patronage to further the interests of the President. …

[There were repeated attempts to impeach the president from late 1866 throughout 1867]

But the President soon gave the House the very opportunity it desired. While the direct attack upon the President was being carried on by means of the effort to impeach him, an indirect attack was made by the legislative limitation of his powers. One of the cries of alarmists had been that there was danger that the President might in some way take advantage of his constitutional position as commander-in-chief of the army and navy, so as to injure the government and advance his own interests. Some went even farther and declared that he designed with the aid of the army to overthrow the government, and place the United States in the power of the rebels. Such charges, viewed from the standpoint of history, seem too absurd for consideration, but during the reconstruction period the feverish condition of the country made possible the acceptance of almost any startling rumor.

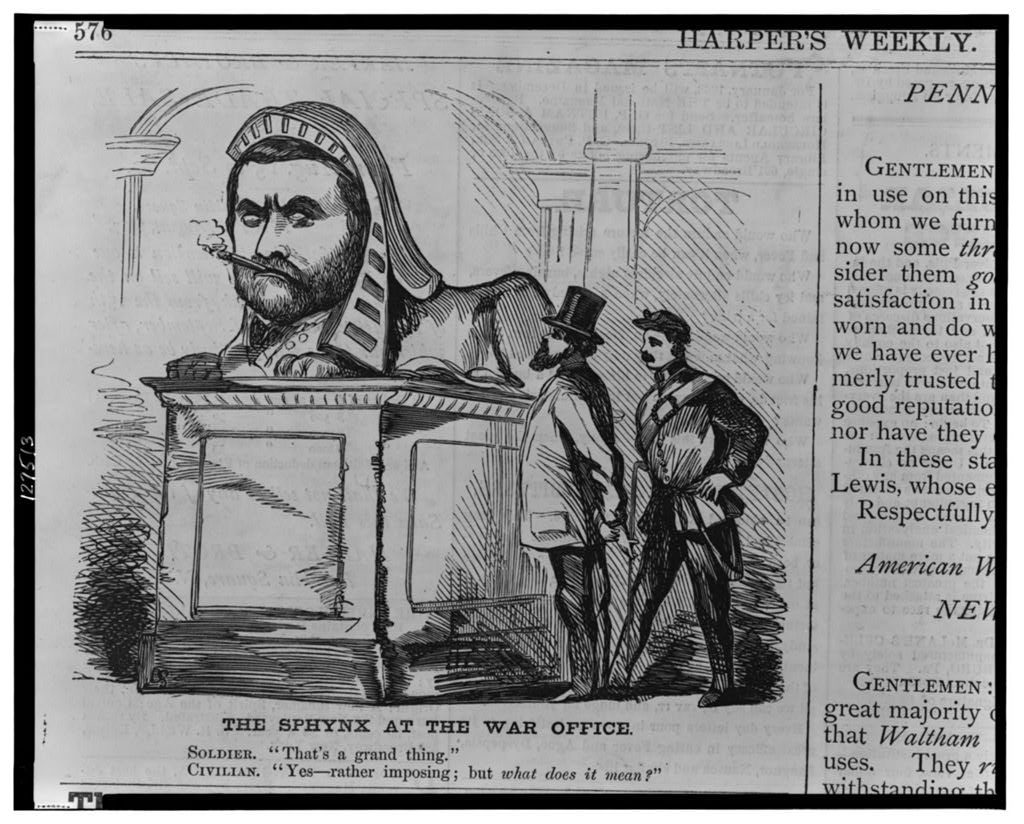

6. But even those who did not apprehend that Johnson would use the army for any improper purpose, were willing to limit his power and prestige by depriving him of his military authority; and this was accordingly done by a section introduced into the army appropriation bill. This section required all orders to the army to be made through the General of the Army, thus practically making his approval of them necessary. It also prevented the President or the Secretary of War from removing, suspending or relieving from command the General of the Army, and even forbade his being assigned for duty away from headquarters, except at his own request. This had the effect of taking away from the President all his constitutional powers as commander-in-chief. As the section was put as a rider on an appropriation bill and a veto must cover the whole bill, Johnson contented himself with a simple protest and returned the act with his signature.

7. The attack upon the civil powers of the President was made through the Tenure-of-Office Act. As the violation of this act was the ground of the most serious charge in the impeachment trial, a somewhat detailed study of its provisions, and of the views expressed by the President in his veto of it, is advisable. The bill provided that “every person holding any civil office to which he has been appointed by and with the advice and consent of the Senate,” and every person so appointed in the future, should be entitled to hold such office until a successor should have been appointed in like manner, that is to say, with the advice and consent of the Senate. The only liberty of action allowed the President was during the recess of the Senate, when he was permitted to suspend an officer until the next meeting of the Senate, and appoint a pro tempore official. Within twenty days after the meeting of the Senate, however, he was required to give his reasons for the suspension. If the Senate approved of the removal, a permanent appointment was to be made; if they refused to concur, the suspended officer was immediately to resume his duties. Any violation of this act by the President was made an impeachable offense, by the declaration that “every removal, appointment, or employment made, had, or exercised, contrary to the provisions of this act * * * are hereby declared to be high misdemeanors.” The other provisions were of minor importance, and do not require notice here.

The veto message of the President was a calm, dignified and judicial discussion of the constitutionality of the bill, and was in every way a creditable document, sustaining fully the high character of his previous vetoes. He called attention to the fact that the whole question of the authority of the President in cases of removal from office had been discussed thoroughly in Congress as early as 1789, and decided in favor of the President. He quoted Madison’s argument to prove that all executive power, except what is specifically excepted, is vested in the President, and that as no exception was made as to the power of removal, it must be vested in him. He also cited many possible cases, in which it would be absolutely necessary for the President to possess the power of removal. A decision of the Supreme Court was referred to, in which it was observed that both the legislative and the executive department had assumed in practice that the power of removal was vested in the President alone. When, for instance, the Departments of State, War and the Treasury were created in 1789, provision was made for a subordinate who should take charge of the office “when the head of the Department should be removed by the President of the United States.” Story, Kent and Webster were all quoted as affirming the same legislative construction of the Constitution. The great practical value of the power during the Civil War was noticed, and its present and future necessity strongly urged; and the message closed with an earnest appeal to Congress not to violate the original spirit of the Constitution.

8. The passage of the bill over the veto placed Johnson in a situation in which a collision was almost sure to come. As the chief executive of the country he was charged with the duty of carrying out the provisions of the reconstruction acts, notwithstanding his strong personal repugnance to them. Under the advice of Attorney-General Stanbery he had construed the acts literally, and he had thus frustrated in part the object of the legislation. But the co-operation of the army was necessary, and unfortunately for President Johnson, the Secretary of War, Mr. Stanton, strongly opposed his views, and conducted himself as far as possible in accordance with the wishes of the congressional majority. The continued friction between the President and the Secretary of War seemed to President Johnson to necessitate Stanton’s retirement, but repeated hints to that effect were not recognized by the latter. Finally, on August 5, 1867, the President informed him that “public considerations of a high character constrained” him to say that his resignation would be accepted. The Secretary’s prompt reply was that “public considerations of a high character” constrained him not to resign until the next session of Congress. A week later, August 12, the President formally suspended him and appointed General Grant Secretary ad interim. Stanton then submitted “under protest to superior force.” …

An editorial in the August 13, 1867 The New-York Times criticized President Johnson’s actions:

Matters at Washington.

Mr. JOHNSON is vindicating his reputation for obstinacy. He has resolved to rid the Government of all who refuse to support his policy, and has begun with Mr. STANTON. Warnings and remonstrances have been disregarded. The danger of doing that which exhibits the Executive in an attitude of implacable hostility to Congress is unheeded. He insists upon his right to throw down the gauntlet, and must take the consequences. …

[Will other Cabinet members continue to be willing to support the president? “Are they willing to be suspected of participation in a course which aims at the decapitation of tried servants and champions of the Union to gratify the malignity of Mr. JOHNSON … People shouldn’t assume that General Grant supports the president’s policies. “His acceptance of the duties of Secretary is temporary and formal, and will neither blind him to the mischief-breeding tendencies of the President’s action nor impair the efficacy of the backing he gives to SHERIDAN, POPE and other objects of Executive hostility.” The president won’t be able to fool the people. “Mr. STANTON is removed, not from maladministration, or corruption, or any wrong-doing of any sort, but solely and simply as a punishment of his sturdy Unionism and his unyielding antagonism to the pro-rebel policy of the President.” Questions about the integrity of the ongoing impeachment proceedings won’t divert public attention from the renewed strife caused by the president’s action. “The question which agitates the country … [is] whether Mr. JOHNSON is or is not abusing the trust reposed in him, and perverting the power he wields to purposes inimical to peace and a restored Union. It is in relation to this question that the suspension of Mr. STANTON possesses significance and peril.”