During the mid-nineteenth century the United States Congress was not in session as much as it is today. In general, Congress did not meet from March until the following December. 1867 was a different kind of year. In March legislation was enacted despite a veto which took over Reconstruction from President Andrew Johnson, whose policies were relatively lenient to the established white South. Congress also passed a law over the president’s veto which limited his power to fire federal officeholders. Because Congress was concerned that President Johnson might ignore the new laws, it did not wait until December to convene the new 40th Congress. Not only did the new Congress convene in March, it also gave itself leeway to reconvene in July instead of December if that was deemed necessary because of the administration’s conduct. It was going to prove necessary:

Johnson’s opportunity to undermine congressional Reconstruction arose after the lawmakers had gone home. In May and June, in two separate opinions, Attorney General Stanbery so interpreted the Reconstruction Acts that voting registrars retained considerable leeway in deciding whom to register. At the same time, Stanbery upheld the authority of the existing governments in the South as well as the supremacy of the civilian courts. In view of the fact that General Sickles and Sheridan had issued orders to the contrary, this opinion created grave problems. Sheridan particularly had sought to enforce the congressional mandate by removing various state and local officers in Louisiana, including in the end, the governor himself. In addition, he had set brief periods of registration because he knew restricting his powers and those of the registrars was forthcoming; in fact, Grant had warned him and informed him that he and Stanton would try to protect him to the best of their ability. … [1]

The following is an 1896 summary of the July 1867 act. It begins with the mindset of Congress when it adjourned in March. While Congress was away, Attorney General Henry Stanbery’s opinion instigated enough Congressmen to return to Washington in July to make a quorum. From The Struggle between President Johnson and Congress over Reconstruction by Charles Ernest Chadsey (pages 122-124):

The passage of the supplementary reconstruction act, and of a joint resolution providing for the expenses involved in carrying out the provisions of the act, completed the work of this session of the 40th Congress. It was hoped that no further congressional action would be needed until the constitutions of the States should be submitted for examination and approval, preparatory to granting representation. But the importance of the measures and the avowed hostility of the President caused hesitation on the part of Congress as to adjourning till the regular December session. It was realized that if any loop-hole could be found by which the intention of the act could be evaded, Johnson would have no hesitation in taking advantage of it. To provide for such a contingency Congress passed a concurrent resolution which provided for a recess until July 3, and authorized the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House to adjourn Congress until the first Monday in December if a quorum did not appear on July 3. In case everything appeared to be progressing with little friction, the members would not assemble; but if there should be any unfavorable developments, Congress could assemble independently of the President and enact legislation to remedy the difficulty.

4. July 3 found a quorum in both houses. The Attorney-General had rendered an opinion upon the act of March 2 which greatly hampered the work of the commanders of the districts. He advised the President that the act should be construed strictly, that the commanders should be allowed no powers beyond those specifically bestowed upon them. This prevented them from removing state officers, from making new laws for the government of the people, or from suspending the action of the state courts; and with state officers hostile to the federal authorities, and using every means to impede their work, the commanders found it impossible properly to discharge the duties assigned to them by the act. The intent of the reconstruction acts obviously was to make the commanders of the districts commanders de facto as well as de jure. Consequently remedial legislation was deemed necessary, and Congress convened for the purpose of framing additional acts defining more precisely the intention of the preceding acts and the powers of the commanders.

A few days’ debate sufficed to bring Congress to an agreement as to the form of a second supplementary act. The bill passed both Houses on July 13, was vetoed on the 19th, and was immediately passed over the veto. It declared the true intent and meaning of the previous reconstruction acts to be that the governments then existing in the ten States specified in the acts were illegal, and that such governments, “if continued, were to be continued subject in all respects to the military commanders of the respective districts, and to the paramount authority of Congress.” It therefore provided that the district commanders should have the power to suspend or remove all incumbents of offices of “any so-called State or the government thereof,” and to fill all vacancies in such offices, however caused. The same powers were granted to the General of the Army, who was also empowered to disapprove the appointments or removals made by the district commanders. The previous appointments by the district commanders were confirmed and made subject to the provisions of the act, and it was declared to be the duty of these commanders to remove from office all who were disloyal to the United States, or who opposed in any way the administration of the reconstruction acts. The registration boards were empowered and required “before allowing the registration of any person to ascertain, upon such facts or information as they can obtain, whether such person is entitled to be registered.” No person was to be disqualified as a member of any board of registration by reason of race or color. The true intent and meaning of the oath prescribed in the supplementary act was fully explained, the most important portion of the explanation being that the words “executive or judicial office in any State” should be construed to “include all civil offices created by law for the administration of any general law of a State, or for the administration of justice.” The time of registration under the supplementary act was extended to October 1, 1867, in the discretion of the commander and it was provided that “the boards of registration shall have power, and it shall be their duty, commencing fourteen days prior to any election under said act, and upon reasonable notice of the time and place thereof, to revise, for a period of five days, the registration lists,” by striking out the names of those found to be disqualified, and adding the names of those qualified for registration. Executive pardon or amnesty should not qualify any one for registration who without it would be disqualified. District commanders were empowered “to remove any member of a board of registration, and to appoint another in his stead, and to fill any vacancy in such board.” The iron-clad oath was to be required of all registration boards, and of all persons elected or appointed to office in the military districts. Further possibility of unfavorable construction by the Attorney-General was prevented by the provision that “no district commander or member of the board of registration, or any of the officers or appointees acting under them, shall be bound in his action by any opinion of any civil officer of the United States.” The closing section, taken in connection with this, was fully as significant: “All the provisions of this act and of the acts to which this is supplementary shall be construed liberally, to the end that all the intents thereof may be fully and perfectly carried out.”

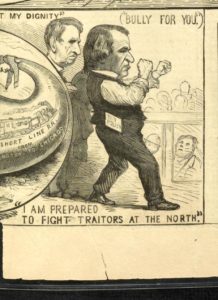

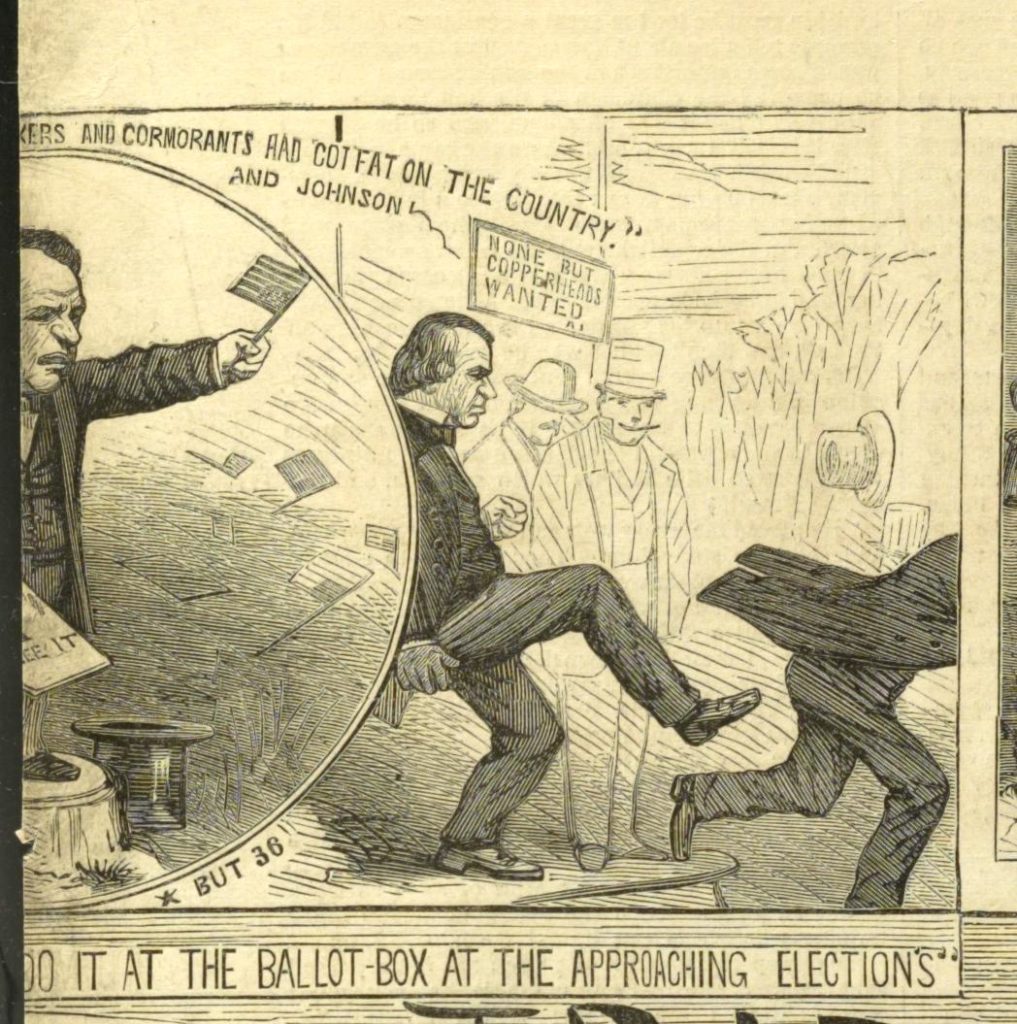

President Johnson’s veto “deplored the imposition of absolute military government over ten states” and objected to Congress curtailing his own Constitutional powers. [2]. You can read Andrew Johnson’s entire veto message at The American Presidency Project. His concluding paragraph:

This interference with the constitutional authority of the executive department is an evil that will inevitably sap the foundations of our federal system; but it is not the worst evil of this legislation. It is a great public wrong to take from the President powers conferred on him alone by the Constitution, but the wrong is more flagrant and more dangerous when the powers so taken from the President are conferred upon subordinate executive officers, and especially upon military officers. Over nearly one-third of the States of the Union military power, regulated by no fixed law, rules supreme. Each one of the five district commanders, though not chosen by the people or responsible to them, exercises at this hour more executive power, military and civil, than the people have ever been willing to confer upon the head of the executive department, though chosen by and responsible to themselves. The remedy must come from the people themselves. They know what it is and how it is to be applied. At the present time they can not, according to the forms of the Constitution, repeal these laws; they can not remove or control this military despotism. The remedy is, nevertheless, in their hands; it is to be found in the ballot, and is a sure one if not controlled by fraud, overawed by arbitrary power, or, from apathy on their part, too long delayed. With abiding confidence in their patriotism, wisdom, and integrity, I am still hopeful of the future, and that in the end the rod of despotism will be broken, the armed heel of power lifted from the necks of the people, and the principles of a violated Constitution preserved.

ANDREW JOHNSON.

Just like in March his veto was immediately overridden.

In an editorial published on July 20, 1867 The New-York Times castigated the president. His combativeness might be amusing if the matter was not so important. “Though Mr. JOHNSON wages battle in his own name, the people of ten States are the victims of his rashness.” Originally his arguments looked strong, but three overridden vetoes showed that his arguments didn’t deal with actual circumstances – and the country wasn’t buying his position. “Of what use is it to appeal to a Constitution which has no binding force or efficacy in the exigency which Congress is required to meet?” The editorial thought that the veto message and especially its final paragraph (above) was “gratuitously offensive” and “insulting”. The president’s position was repudiated “by the people, who are the proper umpires in the controversy.” The editorial’s final paragraph seems to be saying that if President Johnson agreed with the aims of Congressional Reconstruction his logical arguments might be better received. His opposition and the vile way he expressed it show the wisdom of the supplementary act he just vetoed.