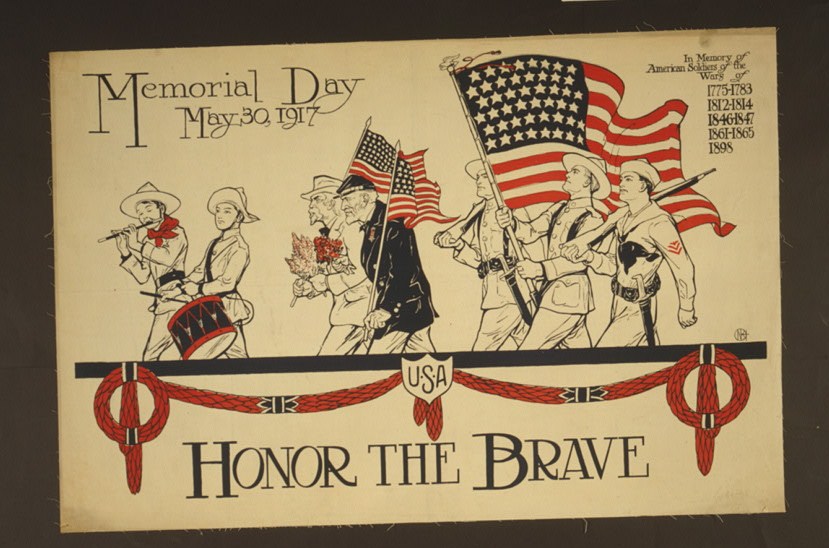

Back in April 1917 the United States declared war on Germany. As young American men were signing up for the draft and getting ready to be shipped to France, the country observed Decoration Day on May 30th. One hundred years ago the transition from Decoration Day to Memorial Day was well underway. Americans weren’t just decorating the graves of Civil War dead; they were honoring the dead from all wars. And living veterans as well. Reportedly, fifty-two years after Appomattox four hundred Civil War veterans marched in New York City’s parade.

From The New-York Times May 31, 1917:

“Many years have passed since a Decoration Day parade in this city aroused so much patriotic enthusiasm as marked the movement of the column of Grand Army veterans and auxiliary down Fifth Avenue yesterday. Probably not since their homecoming from the war ‘back in the sixties’ have the veterans heard such lusty cheers for their tattered flags as they heard on this march down the flag-bordered avenue.”

Thus began the account published in THE NEW YORK TIMES of May 31, 1898, of the Memorial Day parade of that year, a year when the United States was at war with Spain. And with a single change, the substitution of Riverside Drive for Fifth Avenue, the description applies equally well to the parade of this year, when the country is again at war.

There were fewer Grand Army veterans in yesterday’s line of march; their ranks had paid the toll of nineteen years. But the 400 old men who marched yesterday had marched in 1898 and, just as in 1898, they had declared their reception the greatest they had ever experienced, so yesterday the asserted that never before had such a crowd turned out to greet them.

And there were other veterans in the ranks yesterday, not so old, not so grizzled, not so feeble as the Grand Army men, but none the less veterans. They were the men who had fought against Spain …

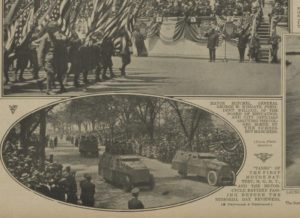

Yesterday the parade trudged along Riverside Drive from the Seventies to the Nineties, a route shorter than the one they traversed in 1898, but still long enough to tax the strength of the Grand Army men, though the martial bands and fife and drum keyed them to unusual vigor. They marched between tight-packed ranks of men, women, and children, sometimes eight and ten deep; between the varied greens of Riverside Park on their left and the flag-covered façades of lofty apartments on their right, between the applause of whistles and sirens from the river and cheers and handclaps from the sidewalk.

A Time for Sobs and Tears.

![Decoration Day [1917] (LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/ggb2005024768/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/24522v-300x203.jpg)

“Memorial Day festivities on Fifth Avenue, at the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Riverside Park, New York City, May 30, 1917”

As they passed the reviewing stand at the base of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument the officers of the various organizations in line brought their side arms to salute, while the rank and file obeyed the crisply shouted commands of “Eyes left.” …

Under the Grand Marshal, Commander Andrew Boyd of the G.A.R., the parade, the parade was ready to start on schedule and presently the long line that took nearly three hours to pass the reviewing stand was under way. …

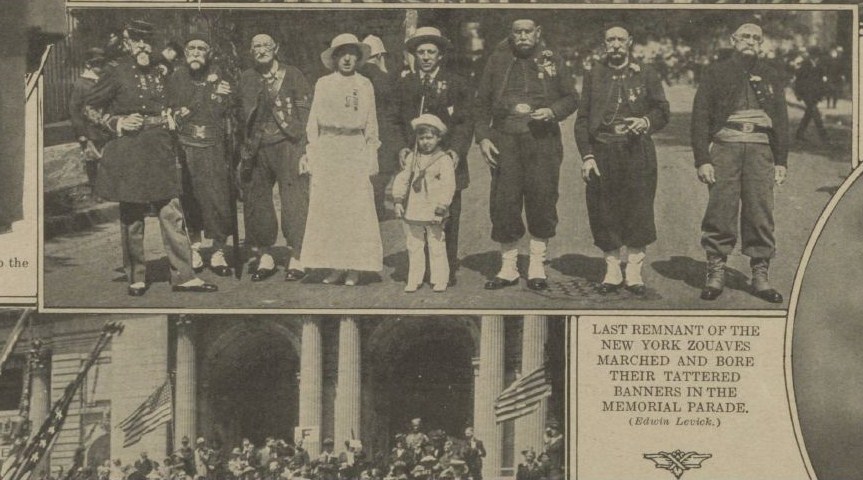

Vets Save Tattered Flags.

With Grand Marshal Boyd at their head, followed by the numerous members of his staff, beneath battle flags so shot and torn that they had been covered with silken nets to keep them from falling apart. They marched as various posts, each under its own colors, and the applause grew frantic as the posts advanced, sometimes three and four men, and once only two, constituting all that was left of civil war companies. There were veterans so feeble that they had to ride in carriages, but they were very few, for it seemed that every man with the strength to walk wanted his place in the line afoot.

Behind them came the Spanish War veterans [and many other units, including “a corps of buglers from the U.S.S. Maine”] …

Uniform Almost Gone.

When Captain Leslie of Phil Kearney Post marched by the reviewing stand in a civil war uniform so tattered that it was held together with pins and pieces of twine the crowd cheered itself hoarse, and Governor Whitman not only swung his hat in salute, but bowed low to the old soldier. He bowed again and repeated it almost continuously as the negro veterans of the civil war filed past. All were old, with kinks of white wool dotting their heads, the most were feeble, but all were proud and strained their aged bodies to stand erect as they passed the reviewing stand.

In their ranks and throughout the line of veterans were many who probably could not have made the march on a less perfect day. After the cold and rain of the preceding days, Memorial Day was brilliantly clear and warm with a warmth that took the kinks out of old legs and put the freshness of Spring into ageing muscles. At it’s conclusion the G.A.R. men declared that never before had there been such a day and such a parade, and then relatives gathered up the excited “oldsters” and in motors and surface cars, the elevated and the subway, hurried them home before the weariness of the march could dull the keenness of their days enjoyment.

In addition to remembering past wars, New York City was also looking forward to the imminent war in France.

![Decoration Day [1917] (1917 (date created or published later by Bain); LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/ggb2005024772/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/24526v-1024x693.jpg)