But what should take its place?

Riots broke out in Richmond, Virginia on May 11, 1867. Two days later ex-Confederate President Jefferson was released on bail in the same city. According to the following report, two of the men who pitched in to bail Mr. Davis out spoke to a gathering in Richmond on the next evening.

From The New-York Times May 15, 1867:

Matters at Richmond – Colored Organizations Disbanded.

RICHMOND, Va., Tuesday, May 14.

Gen. SCHOFIELD has ordered the Lincoln Mounted guards (colored) to disband, and has prohibited their parades or drills. …

The negro laborers in the tobacco warehouses have struck for higher wages. no disturbance has occurred.

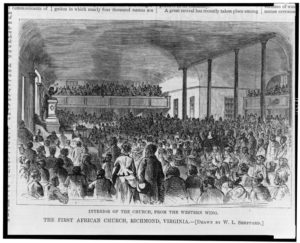

The African Church was densely packed by an audience about equally divided, an assemblage equally as large was gathered outside. Judge PEIRPOINT [sic] was on the stand. Mr. GREELEY explained the obstacles that had impeded reconstruction, beginning with the assassination of ABRAHAM LINCOLN, and coming down to JOHNSON’S policy.The obstacle now was, the unwillingness of the Southern people to give the negro any rights. They were not obliged to do this. If this was overcome there would be peace at the South. The South had the opportunity given it by Congress to give these rights itself, but refused to do it. Upon the subject of confiscation he was emphatic, urging the negroes not to look forward to acquiring lands that way. He wished to see them own farms, but they must work for them, and they need not expect to get them in any other way.GARRETT SMITH followed in a short address. He said the South was not alone to blame for the war which had been brought on by the North, which had supported slavery, its immediate cause. It had supported slavery because it had profited by it. It had drawn the milk while the South held the cow. He strongly opposed confiscation and told the negoroes not to look forward to anything that was so hopeless. In allusion to the rumors of the riots which he had heard of since arriving here, he urged the negroes not to give way to lawlessness, and to avoid any approach to riotous conduct.

Judge UNDERWOOD, who was cheered and hissed as he came forward, made a short address. …

According to Eric Foner, many Northern blacks “carried south the ideology of free labor, with its respect for private property and individual initiative.” Many people in the “Southern free black elite” supported those ideas and “opposed talk of confiscation and insisted that political equality did not imply the end of class distinctions.” But talk of confiscation was especially powerful in 1867 because “successive crop failures had left those on share contracts with little or no income and caused a precipitous decline in cash wages.” 1867 was a bad time to “preach individual self-help to black belt freedmen,” who felt poor and dependent. “Rural blacks raised, once again, the demand for land.” The 1867 “Reconstruction Act rekindled the belief that the federal government intended to provide freedmen with homesteads”.[1]

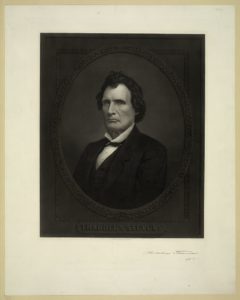

One member of the white Northern elite who supported confiscation was Thaddeus Stevens. The May 18, 1867 issue of Harper’s Weekly (page 306) thought the Pennsylvania Congressman’s version of “a mild confiscation” might be inexpedient, but it knew where he was coming from:

… But it is very foolish to speak of Mr. STEVENS’s desire of confiscation as a frantic act of vengeance. His philosophy is very far from ridiculous. Mr. STEVENS, of course, does not suppose that the late rebels, as a rule, are friendly to the freedmen. He sees them soliciting the freedmen’s votes because they are essential to their political success. He knows that the white leaders who are hostile to the Union party will use every means to obtain control of the colored vote. He also sees that no provision whatever has been made for giving the freedmen land; and he knows, as every reflecting man knows, that without land they lack a vital element of substantial citizenship. Now voters who must work upon the land every day to live are immediately dependent for bread upon the landholders; and where, as in the South, the late masters are the landholders and the late slaves are the laborers it is easy to see what an influence can be exerted. …

According to a letter Congressman Stevens wrote to local officials, confiscation for the benefit of the southern freedmen was only a part of a larger confiscation scheme. From The New-York Times June 2, 1867:

A New Phase of Confiscation – Another Letter from Hon. Thaddeus Stevens.

From the Bedford (Pa.) Inquirer.

LANCASTER, Thursday, May 23, 1867.

[To various county and town officials]

GENTLEMEN: As I am about to prosecute the claims for confiscation at the next session of Congress, if I should be permitted to appear there, I desire to ascertain certain facts. Will you aid me in procuring them in a small part of our own State? Invite returns from all the people in each township of the amount of property which the rebel raiders, or the armies of the so-called “Confederate States,” destroyed or appropriated to their own use during their several incursions into Pennsylvania, and hand the same to the Assessors of the different townships, who are requested to return the aggregate to the Chairmen of the respective parties of the different counties. May I here ask that the various newspapers of the counties above named, publish this notice for a few weeks in aid of the object specified as I intend to press the payment of the damages done to loyal men, out of the confiscated property of the conquered belligerent. …

THADDEUS STEVENS

P.S. [He would like all the people of all the loyal states to eventually tally up their losses and be recompensed from the confiscated property.]

… I trust that it will not be supposed that I have abandoned the determination to procure small homesteads for the freedmen, to be furnished by the rebel masters whom they conquered at our request – homesteads earned by the late slaves and annexed to their master’s estates. Let them now be severed by partition. …

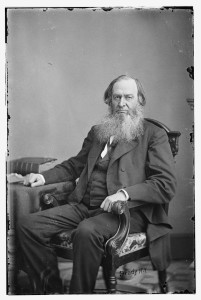

Could Horace Greeley’s opposition to confiscation be a symptom of his strong Whig values? Adam Tuchinsky [2] wrote that “[p]erhaps the most dramatic example of the postwar revival of Greeley’s Whiggery was his role in securing the release of Jefferson Davis from jail. Greeley’s gesture to Davis reflected his fervent hope that that the ‘better classes’ of the North and the South could be reconciled.” Even though his newspaper was “packed with reports of Southern racism and violence,” Mr. Greeley’s benevolence toward Jeff Davis was an example of “one more eruption of his intrinsic Whiggery, his faith that all conflicts, social and sectional, could be reasonably harmonized.” His opposition to confiscation might also come from the Whig view that society is organic. Individuals and institutions have different abilities and different roles to play, which can work together. “This Whig sensibility recoiled in horror from violence, passion, conflict, crime, and especially insurrection and war – all represented a breakdown of discipline and reason.”From the Library of Congress: inside the First African Church from the June 27, 1874 issue of Harper’s Weekly; outside in 1865 (original building not torn down until 1876); Gerrit Smith, Thaddeus Stevens, and Horace Greeley

- [1]Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: HarperPerennial, 2014. Updated Edition. Print. pages 289-290.↩

- [2]Tuchinsky, Adam. Horace Greeley’s New-York Tribune: Civil War-Era Socialism and the Crisis of Free Labor. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009. Print. page 221.↩

![[Richmond, Va. First African Church (Broad Street)] (1865; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/cwp1994000694/pp/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/02904v-300x300.jpg)

![Journalist and abolitionist Horace Greeley wearing hat ([between 1860 and 1872]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2016652257/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/49763v-190x300.jpg)