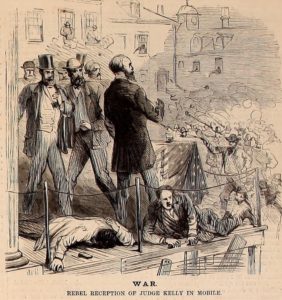

150 years ago earlier this week a riot broke out in Mobile, Alabama. From The New-York Times May 15, 1867:

RIOT IN MOBILE.

Attack by Secessionists upon Judge Kelley – Several Men Shot.

MOBILE, Tuesday, May 14.

A large number of negroes met to night at the corner of Government and Royal streets, to hear Judge KELLEY, of Pennsylvania. A number of whites were also present, and everything was remarkably quiet until Judge KELLEY began speaking, saying he had come to discuss the rights of negroes. He declared he was entitled to a hearing, and bid defiance to all interruptions and to the world. He had the Fifteenth Regiment at his back; if they proved inadequate, he would have the whole United States Army. Judge KELLEY continued this strain some minutes, using language and expressions of an incendiary character, and sentiments which were calculated to lead and invite riotous demonstrations. He was interrupted by a white man on the outskirts of the crowd, whom the Police promptly arrested. The first shot was fired at this point. It was impossible to say who it was fired by; instantaneously shots followed from the negroes, who were all armed. The firing then became general. Immediately after the firing began, an alarm was rung, and continued ringing during the progress of the riot, which lasted about an hour. A large majority of the shots were fired by negroes, as but very few of the whites present were armed. The police succeeded in quelling the riot before the arrival of the companies of the Fifteenth Regiment, who were ordered out by Col. SHEPHERD, and appeared on the ground as soon as possible, but not until the meeting had been dispersed. They now guard the streets. Everything is quiet, and there was little or no excitement at midnight. It is impossible to state positively the number of killed and wounded.

Three men are known to have been killed, one a white man, and two negroes. A number are wounded, among them one policeman and a white boy.

Judge KELLEY is at the Battle House, and leaves to-morrow for Montgomery.

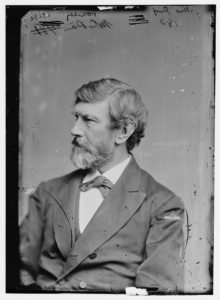

The same correspondent provided further particulars the next day, including the fact the army was posted throughout the city, including a squad of soldiers guarding the Battle House. An editorial in the May 16, 1867 issue of The New-York Times was concerned about the violence and black demands for confiscation and political supremacy extreme radicalism was stirring up in various southern states. The editorial maintained that, although free speech was fundamental and everyone had the right to say whatever they wanted wherever they wanted without fearing for their life, Mr. Kelley and other radicals speaking in the South should be more prudent:

Here, we take it, is the fundamental error of the extremists as agitators at the South: they forget that political discussion, to be useful, should be temperate and reasonable, and they disregard the prudence which dictates courtesy and conciliation as the surest avenues to the judgment of the Southern people. They make the mistake of imagining that to be preëminently loyal it is necessary to be preëminently abusive, and that the pacification and reorganization of the South may be promoted by scolding and threatening rather than by forbearance and generosity.

Walter L. Fleming in his 1905 Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama (page 509) laid the blame for the Mobile riot directly on Mr. Kelley:On May 14, Judge “Pig Iron” Kelly of Pennsylvania spoke in Mobile to an audience of one hundred respectable whites and two thousand negroes, the latter armed. His language toward the whites was violent and insulting, an invitation for trouble, which inflamed both races. A riot ensued for which he was almost solely to blame. Several whites were killed or wounded and one negro. From the guarded report of General Swayne it was evident that the blame lay upon Kelly for exciting the negroes. It was a most unfortunate affair at a critical period, and the people began to understand the kind of control that would be exercised over the blacks by alien politicians.

On the other hand, the June 1, 1867 issue of Harper’s Weekly copied a report from another newspaper and maintained there wasn’t much inflammatory in Mr. Kelley’s speech – at least by the time he gave it Montgomery (page 339):

ALARMING.

WE find the following atrocious sentiments in the speech delivered at Montgomery a day or two after the Mobile riot by that fanatical incendiary and radical disorganizer, Judge KELLEY. We quote from the report in the New York Herald:

“He urged them to build rolling-mills, erect furnaces, employ the water-power at Wetumpka and up in the other cotton districts, and to rotate their crops as we do in the North. The day will come when Alabama will not confine herself to cotton as her sole crop, but she will send her railroad iron to the Gulf. The wives and daughters of men as dusky as those around him would spin the cotton. They need not tell him they can’t do it; for he had visited the colored schools and found enough of talent and intelligence there to convince him that they had the laborers at hand if they only trained them. Addressing the white people, Mr. KELLEY said he failed to find any other reason for the difference between the North and South than their contempt for the rights of man as man. He urged them to set aside their prejudices and reconstruct the South promptly and willingly. If that were done he would declare, in behalf of the whole country, that the present laws of Congress would be a finality unless it was driven to enact harsher measures, and before many years the South would be more liberal and as prosperous as the North. He then addressed the freedmen, reminding them that their freedom meant the right to toil for their living and get paid for it, but in doing so they must be just to all. Freedom means that a good man is better than a bad man, and the smart man wins the race. They were at liberty to protect their wives, and they should take care of them, and send their children to school, that they might have a lighter task to endure than their fathers. They must live in peace with the people of Alabama. They will have to pay taxes and study the politics of their country. Let those who were mechanics try to start for themselves, and those who were farm-laborers should avail themselves of the homestead law; or, if the government lands were too far away, Congress would see that land-offices should be brought nearer to the people. He was not the agent of a party, but he loved the party he belonged to because of its great principles. Devotion to the Union and belief in the rights of man were its two bases.”

![mobile and defenses (The Philadelphia Inquirer, [newspaper]. April 18, 1865; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/scsm001262/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/mobile-and-defenses-270x300.jpg)

![The Philadelphia Inquirer, [newspaper]. April 18, 1865. (https://www.loc.gov/resource/lprbscsm.scsm1262/?sp=1)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/PI4-18-1865.jpg)