In January 1867 the United States Congress passed a law over President Johnson’s veto that guaranteed the right to all men in the District of Columbia “without any distinction on account of color or race.” 150 years ago today black men voted for the first time in an election in Georgetown. According to one editorial, white men in Georgetown who boycotted the election because of the black voters sort of shot themselves in the foot. From The New-York Times February 27, 1867:

… Special Dispatches to the New-York Times.

WASHINGTON, Tuesday, Feb. 26. …

THE ELECTION IN GEORGETOWN.

The Georgetown election, which took place yesterday, affords some curious and amusing instances of the extremes to which men, calling themselves white, and believing themselves possessed of sense, will be led by their passions and prejudices. The Republican candidate, Mr. CHARLES D. WELSH, who planted himself squarely on the platform of negro suffrage, was elected by ninety-six majority; and the same party elected seven out of eleven members of the Common Council. The entire vote was about 1,900, while the registry was over 2,300. It is an indisputable fact that the colored vote, only about 900 of the aggregate, was thoroughly polled, for they were at the polls early, and brought out every man in their eagerness to improve the first opportunity for the exercise of the long-sought boon of free suffrage. The presence of the colored men at the polls was so distasteful to the whites that many refused to vote while a black voter was near the ballot-box, and at least three hundred registered white men refused to go near the polls. The result was that they were beaten, as they deserved to be, when they really had it in their own power to beat their opponents. A few men have even gone so far as to threaten to discharge some of their colored employees because they dared to vote at all. One of this class was brought to his senses this morning by being informed by two of his best customers, that if he carried his politics into his business to that extent, they would also carry their politics into his business by withdrawing their patronage. …

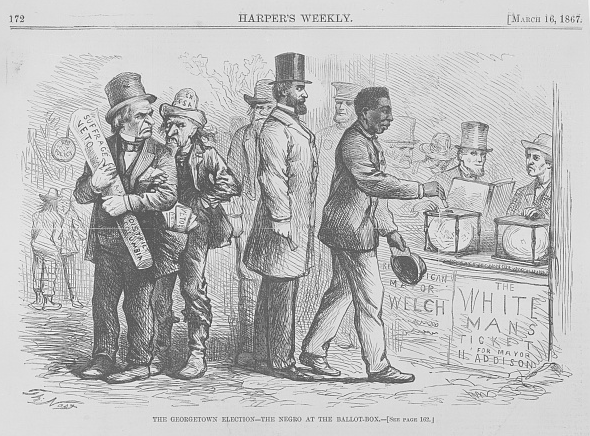

Thomas Nast’s cartoon was published in the March 16, 1867 issue of Harper’s Weekly. On page 162 in the same issue the magazine reported that the election showed “that the colored citizen is intelligent enough to know his interest, and independent enough to act accordingly. The horrible consequences of the vice and ignorance of colored voters are not yet apparent” – they didn’t seem beholden to “massa.” The freedman’s conduct was dignified, decorous, and restrained. Because some Baltimore and Washington roughs and bullies had threatened to show up, 150 policemen were on hand. There were sneers and insults, which the freedmen disregarded, and “the peace was not broken.” The election “was an ample vindication of the wisdom of Congress in passing the suffrage bill, and of those who insist that justice is the best policy.”

Slavery was abolished in the District of Columbia on April 16, 1862.

![Johnson's Georgetown and the city of Washington : the capital of the United States of America. (New York : A.J. Johnson, [1867] ; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/88693495/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/dc1867-1024x805.jpg)