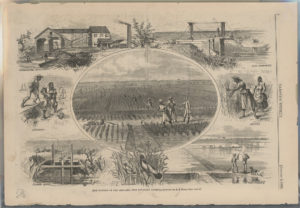

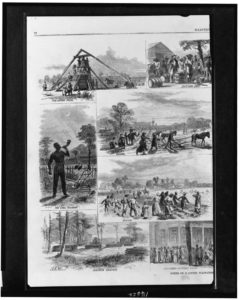

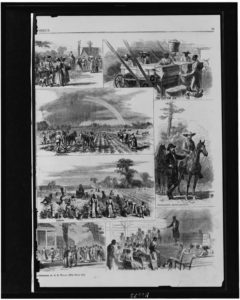

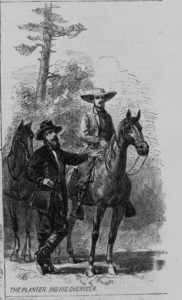

Almost two years after the Civil War ended Alfred R. Waud was still providing illustrations from the front for Harper’s Weekly. Back in January his drawings of a rice plantation in Georgia were published. The February 2, 1867 issue of Harper’s Weekly (page 69) included Mr. Waud’s observations of southern cotton plantations. “These pictures were mainly taken upon the Buena Vista plantation, in Clarke County, Alabama.” The accompanying text went on to explain the process of growing cotton and processing it into bales for shipment and sale. The picture of the plantation graveyard for “defunct negroes” shows the rail fence above the graves to keep away marauding animals. The former slaves put a mattock and a spade on each new grave for fourteen days to prevent “premature resurrection of the corpse”. Cotton growing was still profitable in the South, even with free labor replacing slavery:

… One man to ten acres is considered sufficient – if they work. A good hand before the war was worth $1500 in gold, which, at the Alabama rate of interest – 8 per cent. – was $120 a year, besides the clothing, taxes, doctor’s bill, loss of time during sickness, insurance, etc. The same hand can now be hired for $10 a month in currency; pay’s his own doctor’s bill and taxes, clothes himself, deducts all time lost by sickness, and if he dies is his own loss – a consoling reflection to some planters.

Horses and mules can be purchased for less in currency than they could before the war, while provisions are about the same when reduced to a gold basis. The richest lands are for sale for prices one half to one third less than before the war. …

According to Walter L. Fleming in his 1905 Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama (pages 322-324) many Yankees took advantage of the cheap land:

Immigration to Alabama

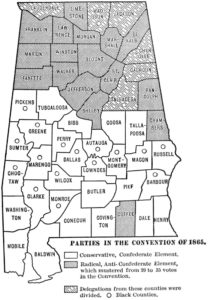

As soon as the war was ended, there was an influx of northern men and northern capital into Alabama. Cotton was selling at a fabulous price,—40 to 50 cents a pound, $200 to $250 a bale,—and the newcomers expected to make fortunes in a few years. They were welcomed by the planters who wanted to sell or to lease their plantations, which, for want of funds, they were unable to cultivate. General Swayne said that in 1866 there were 5000 northern men in Alabama engaged in trading and planting. They were sought for as partners or as overseers by those who hoped that northern men could control free negro labor. Lands were sold or leased at low prices, and many soldiers, especially officers, decided to buy land and raise cotton. Numbers of large plantations in the Black Belt were bought or leased by officers of the army, all of whom had lofty ideas as to what they were going to do. The soil was fertile, cotton was selling for high prices, and the free blacks, they were sure, would work for them out of gratitude and trust. They wanted to help reconstruct southern industry, and to show what could be done toward developing the great natural resources of the state. They embarked in large enterprises, and as long as their money lasted bought everything that was offered for sale. Their success or failure was dependent largely upon the negro laborer, who was to make the cotton, and the new planters made extraordinarily liberal terms with him. They dealt with the negro as if he were a New Englander with a black skin, and they purchased expensive machinery for him to use. They would not listen to southern advice, but went as far as possible to the opposite extreme from southern methods of farming. All suggestions were met with the assurance that the southern man was used only to slaves, and could not know how free men would work.

Reports, generally false and made mainly for political purposes, were continually published by the northern press in regard to the ill treatment of northern men who wished to make their homes in the South. But not a single authenticated case of violence to such persons can be found to have taken place in Alabama.

In some localities, on account of bands of outlaws, for several months after the war it was not safe for any stranger to settle. The ignorant whites had no liking for the northern men (and may not have to this day). The better class of people was in favor of much immigration from the North, and Governor Parsons made a tour through the North to induce northern men and capital to come to Alabama. The people had no capital, and wanted to induce those who possessed it to come and live in the state. The testimony of travellers was that the accounts of cruelty and intolerance toward northerners were almost entirely false; that they were welcomed if they did not attempt to stir up trouble between the races. The refusal of Congress to recognize the state government and the rejection of the members elected to Congress caused a fresh outburst of bitter feeling against the North; but General Swayne, who had the best opportunities for observation, said that rudeness and insult and the occasional attentions of a horse-thief were the worst things that had happened to the northern settlers.

These northern men meant well but, as a rule, were incompetent as farmers and business men. Consequently they failed, and most of them never quite understood the reasons for their failure. They knew next to nothing of plantation economy, and the negroes were their only teachers. Most of them were from the West, and had never seen cotton growing before. It was almost pathetic to see these 5000 northerners risking all they possessed upon their faith in the negro, and losing. The northern merchant gave the negro unlimited credit and lost; the planter gave his tenant all he asked for, whenever it pleased him to ask. The farm stock was driven to camp-meetings and frolics while the grass was killing the cotton. Mills and factories were built and negro laborers employed, but the negroes, because of a lack of quickness and sensitiveness of touch, proved to be unfit for factory work. Besides, the noise of the machinery made them sleepy, and it was beyond their power to report for work at a regular hour each morning. At first, the negroes showed great confidence in the northern man and were glad to work for him, but too much was required of them, and after a year or two the disgust was mutual. The revulsion of feeling following failure and disappointment and ostracism injured the South by creating hostile opinion in the North. Nearly all the northern men went home, but the less desirable ones remained to assist in the political reconstruction of the state, when many of them became state officials.

The above stories are two tiny snapshots of the complex change in Southern society from slavery to free labor, and it would seem that people’s prejudices made the problem more complicated. In his book on Reconstruction Eric Foner details the complexity and some of the prejudices in a section entitled Masters Without Slaves[1] Mr. Foner writes about the Northerners who moved South and invested their money in cotton production. The Yankees were generally welcomed at first:

… most Southern planters recognized that Northern investment, ironically, was raising land prices and rescuing many former slaveholders from debt – in a word. stabilizing their class. What most annoyed Southern whites was the newcomers’ sublime confidence that they knew better than former slaveowners how to supervise free black labor. “They believed, in their supercilious folly,” one planter later wrote, “that they could get along with the free negroes as laborers, and teach the Southerners how to manage them.”

Southern planters predicted that the newcomers would soon complain about the character of black labor, and they were not far wrong. …

The blacks preferred a more irregular pace of work and wanted to “direct their own labor.”[2]

The February 2, 1867 Harper’s Weekly piece concluded that even with free labor cotton growing should be a profitable business, but the current growing season was the worse since 1846. Mr. Foner says that 1866 and 1867 were terrible years for cotton because of the weather and the army worm. “Many planters suffered devastation losses in these years.”[3]

A current study finds that blacks spend more time not working at work than whites (although they labor more than Hispanics). Daniel Hamermesh, one of the researchers, was quickly “labelled a racist in an online forum popular among economists.” That’s not fair because Mr. Hammeresh sort of puts blacks and Hispanics on a pedestal – he wants everyone to work less. [4] Are the critics racist in a way because they assume the white work ethic is superior?A?h6>

Also, I have learned that some people might consider my title racist

Thomas Nast, a cartoonist for Harper’s Weekly, highlighted southern white mistreatment of blacks. According to the Library of Congress Mr. Nast also produced a Grand Caricaturam, a series of paintings on American History. One of his paintings portrayed King Cotton as dependent on slavery.

___________________________________________________

![[Gettysburg, Pa. Alfred R. Waud, artist of Harper's Weekly, sketching on battlefield] (by Timothy H. O'Sullivan, 1863 July; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/cwp2003000198/PP/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/00074v-300x234.jpg)