150 years ago this week President Andrew Johnson kept chalked up a couple more vetoes by opposing statehood bills for Colorado and Nebraska. You can read both veto messages at the Miller Center of the University of Virginia (Colorado andNebraska). The president didn’t think either state was populous enough to support a state government; In the Colorado message he included a protest from inhabitants who were concerned about the expenses of state government. Mr. Johnson was also concerned that the population of each territory was well below the number that would allow a state to gain another representative in the U.S. House (127,000 in 1867).

In both cases the United States Congress submitted bills to the president that would make Colorado and Nebraska states only if their respective legislatures enacted laws ensuring voting rights regardless of race or color. President Johnson objected to this because the U.S. Constitution gave individual states the right to determine voting qualifications. Since Congress was changing the state constitution which Nebraskans adopted, the president wondered whether the mandated change in the electoral law should be put before the voters in Nebraska as a referendum.

Here is President Johnson’s Nebraska message from Project Gutenberg:

WASHINGTON, January 29, 1867.

To the Senate of the United States:

I return for reconsideration a bill entitled “An act for the admission of the State of Nebraska into the Union,” which originated in the Senate and has received the assent of both Houses of Congress. A bill having in view the same object was presented for my approval a few hours prior to the adjournment of the last session, but, submitted at a time when there was no opportunity for a proper consideration of the subject, I withheld my signature and the measure failed to become a law.

It appears by the preamble of this bill that the people of Nebraska, availing themselves of the authority conferred upon them by the act passed on the 19th day of April, 1864, “have adopted a constitution which, upon due examination, is found to conform to the provisions and comply with the conditions of said act, and to be republican in its form of government, and that they now ask for admission into the Union.” This proposed law would therefore seem to be based upon the declaration contained in the enabling act that upon compliance with its terms the people of Nebraska should be admitted into the Union upon an equal footing with the original States. Reference to the bill, however, shows that while by the first section Congress distinctly accepts, ratifies, and confirms the Constitution and State government which the people of the Territory have formed for themselves, declares Nebraska to be one of the United States of America, and admits her into the Union upon an equal footing with the original States in all respects whatsoever, the third section provides that this measure “shall not take effect except upon the fundamental condition that within the State of Nebraska there shall be no denial of the elective franchise, or of any other right, to any person by reason of race or color, excepting Indians not taxed; and upon the further fundamental condition that the legislature of said State, by a solemn public act, shall declare the assent of said State to the said fundamental condition, and shall transmit to the President of the United States an authentic copy of said act, upon receipt whereof the President, by proclamation, shall forthwith announce the fact, whereupon said fundamental condition shall be held as a part of the organic law of the State; and thereupon, and without any further proceeding on the part of Congress, the admission of said State into the Union shall be considered as complete.” This condition is not mentioned in the original enabling act; was not contemplated at the time of its passage; was not sought by the people themselves; has not heretofore been applied to the inhabitants of any State asking admission, and is in direct conflict with the constitution adopted by the people and declared in the preamble “to be republican in its form of government,” for in that instrument the exercise of the elective franchise and the right to hold office are expressly limited to white citizens of the United States. Congress thus undertakes to authorize and compel the legislature to change a constitution which, it is declared in the preamble, has received the sanction of the people, and which by this bill is “accepted, ratified, and confirmed” by the Congress of the nation.

The first and third sections of the bill exhibit yet further incongruity. By the one Nebraska is “admitted into the Union upon an equal footing with the original States in all respects whatsoever,” while by the other Congress demands as a condition precedent to her admission requirements which in our history have never been asked of any people when presenting a constitution and State government for the acceptance of the lawmaking power. It is expressly declared by the third section that the bill “shall not take effect except upon the fundamental condition that within the State of Nebraska there shall be no denial of the elective franchise, or of any other right, to any person by reason of race or color, excepting Indians not taxed.” Neither more nor less than the assertion of the right of Congress to regulate the elective franchise of any State hereafter to be admitted, this condition is in clear violation of the Federal Constitution, under the provisions of which, from the very foundation of the Government, each State has been left free to determine for itself the qualifications necessary for the exercise of suffrage within its limits. Without precedent in our legislation, it is in marked contrast with those limitations which, imposed upon States that from time to time have become members of the Union, had for their object the single purpose of preventing any infringement of the Constitution of the country.

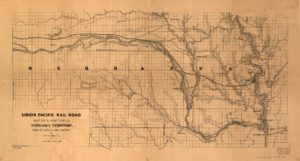

If Congress is satisfied that Nebraska at the present time possesses sufficient population to entitle her to full representation in the councils of the nation, and that her people desire an exchange of a Territorial for a State government, good faith would seem to demand that she should be admitted without further requirements than those expressed in the enabling act, with all of which, it is asserted in the preamble, her inhabitants have complied. Congress may, under the Constitution, admit new States or reject them, but the people of a State can alone make or change their organic law and prescribe the qualifications requisite for electors. Congress, however, in passing the bill in the shape in which it has been submitted for my approval, does not merely reject the application of the people of Nebraska for present admission as a State into the Union, on the ground that the constitution which they have submitted restricts the exercise of the elective franchise to the white population, but imposes conditions which, if accepted by the legislature, may, without the consent of the people, so change the organic law as to make electors of all persons within the State without distinction of race or color. In view of this fact, I suggest for the consideration of Congress whether it would not be just, expedient, and in accordance with the principles of our Government to allow the people, by popular vote or through a convention chosen by themselves for that purpose, to declare whether or not they will accept the terms upon which it is now proposed to admit them into the Union. This course would not occasion much greater delay than that which the bill contemplates when it requires that the legislature shall be convened within thirty days after this measure shall have become a law for the purpose of considering and deciding the conditions which it imposes, and gains additional force when we consider that the proceedings attending the formation of the State constitution were not in conformity with the provisions of the enabling act; that in an aggregate vote of 7,776 the majority in favor of the constitution did not exceed 100; and that it is alleged that, in consequence of frauds, even this result can not be received as a fair expression of the wishes of the people. As upon them must fall the burdens of a State organization, it is but just that they should be permitted to determine for themselves a question which so materially affects their interests. Possessing a soil and a climate admirably adapted to those industrial pursuits which bring prosperity and greatness to a people, with the advantage of a central position on the great highway that will soon connect the Atlantic and Pacific States, Nebraska is rapidly gaining in numbers and wealth, and may within a very brief period claim admission on grounds which will challenge and secure universal assent. She can therefore wisely and patiently afford to wait. Her population is said to be steadily and even rapidly increasing, being now generally conceded as high as 40,000, and estimated by some whose judgment is entitled to respect at a still greater number. At her present rate of growth she will in a very short time have the requisite population for a Representative in Congress, and, what is far more important to her own citizens, will have realized such an advance in material wealth as will enable the expenses of a State government to be borne without oppression to the taxpayer. Of new communities it may be said with special force—and it is true of old ones—that the inducement to emigrants, other things being equal, is in almost the precise ratio of the rate of taxation. The great States of the Northwest owe their marvelous prosperity largely to the fact that they were continued as Territories until they had growth to be wealthy and populous communities.

ANDREW JOHNSON.

On the other hand, President Johnson didn’t veto the Territorial Suffrage Act of January 10, 1867. The bill, which prohibited “denial of the elective franchise in any of the Territories of the United States, now or hereafter to be organized, to any citizen thereof on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” became law without the president’s signature.

Congress voted to override the Nebraska veto – the territory would soon become the 37th state. Congress did not override the Colorado veto.