As 1867 began, newspaper headlines indicated that the United States Congress was definitely planning on impeaching President Andrew Johnson. The president wasn’t cowed. On January 7th Congress received his veto of An act to regulate the elective franchise in the District of Columbia, which specifically mandated that the right to vote was guaranteed to every man in the District “without any distinction on account of color or race.”

You can read the veto message at The American Presidency Project. It was a long message. Two of President Johnson’s points: Congress was ignoring the will of existing D.C. voters; by prohibiting the Southern States representation in the national legislature Congress was ensuring it was veto-proof:

… Measures having been introduced at the commencement of the first session of the present Congress for the extension of the elective franchise to persons of color in the District of Columbia, steps were taken by the corporate authorities of Washington and Georgetown to ascertain and make known the opinion of the people of the two cities upon a subject so immediately affecting their welfare as a community. The question was submitted to the people at special elections held in the month of December, 1865, when the qualified voters of Washington and Georgetown, with great unanimity of sentiment, expressed themselves opposed to the contemplated legislation. In Washington, in a vote of 6,556–the largest, with but two exceptions, ever polled in that city–only thirty-five ballots were cast for Negro suffrage, while in Georgetown, in an aggregate of 813 votes–a number considerably in excess of the average vote at the four preceding annual elections–but one was given in favor of the proposed extension of the elective franchise. As these elections seem to have been conducted with entire fairness, the result must be accepted as a truthful expression of the opinion of the people of the District upon the question which evoked it. Possessing, as an organized community, the same popular right as the inhabitants of a State or Territory to make known their will upon matters which affect their social and political condition, they could have selected no more appropriate mode of memorializing Congress upon the subject of this bill than through the suffrages of their qualified voters.

Entirely disregarding the wishes of the people of the District of Columbia, Congress has deemed it right and expedient to pass the measure now submitted for my signature. It therefore becomes the duty of the Executive, standing between the legislation of the one and the will of the other, fairly expressed, to determine whether he should approve the bill, and thus aid in placing upon the statute books of the nation a law against which the people to whom it is to apply have solemnly and with such unanimity protested, or whether he should return it with his objections in the hope that upon reconsideration Congress, acting as the representatives of the inhabitants of the seat of Government, will permit them to regulate a purely local question as to them may seem best suited to their interests and condition. …

In addition to what has been said by these distinguished writers, it may also be urged that the dominant party in each House may, by the expulsion of a sufficient number of members or by the exclusion from representation of a requisite number of States, reduce the minority to less than one-third. Congress by these means might be enabled to pass a law, the objections of the President to the contrary notwithstanding, which would render impotent the other two departments of the Government and make inoperative the wholesome and restraining power which it was intended by the framers of the Constitution should be exerted by them. This would be a practical concentration of all power in the Congress of the United States; this, in the language of the author of the Declaration of Independence, would be “precisely the definition of despotic government.” …As shown in charts at Wikipedia, the Republican majorities in both House and Senate in the 39th United States Congress were veto-proof, given the exclusion of southern states. As documented at The Daily Render, Congress did indeed override the veto by January 8th.

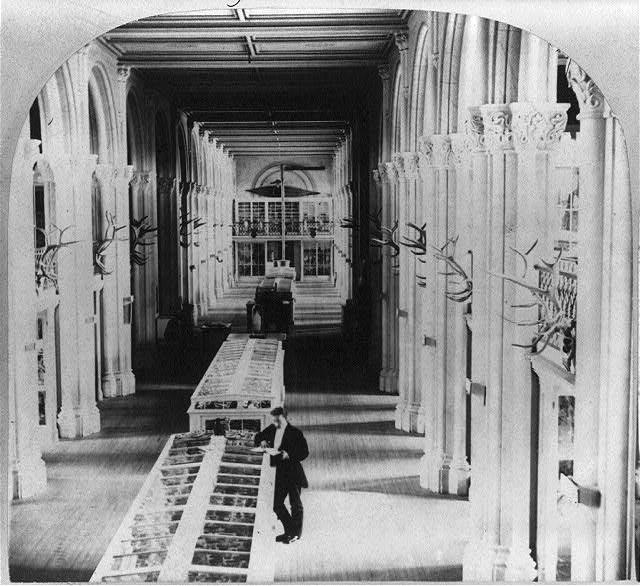

The Library of Congress provides the image of Congressional Library at the U.S Capitol. The Library of Congress didn’t move out until 1897. The image of exhibit cases at the Smithsonian Institution also comes from the Library. Andrew Johnson served as a representative from Tennessee in the U.S. House from 1843 until 1853. According to Hans L. Trefouse, he generally supported economy in government and consistently opposed the Smithsonian Institution. In the fall of 1847 Congressman Johnson exhibited an “ever more pronounced vendetta against the Smithsonian Institution, which he attacked at every opportunity. After advocating the establishment of a committee of supervision for the institution, he so severely criticized one of its regents, his fellow congressman Henry W. Hilliard of Alabama, that members of the House were appalled.” David Outlaw of North Carolina denounced the “real demagogical speech.” [1]

- [1]Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & company, Inc., 1997. Print. page 69.↩

![Congressional Library, (In U.S. Capitol) / photographed and published by Bell & Bro., 480 Penn, Avenue, Washington, D.C. ([Washington, D.C.] : [Bell & Bro.] [1867]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/cph24851/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/3a07879r-300x291.jpg)