A document at the Library of Congress indicates that 150 years ago today the Grand Council of the Union League of Alabama wrote an epistle to its local branches. The letter began by thanking God that thanks to federal soldiers Alabamans could publicly proclaim the doctrine that “all men are created equal.” It discussed the 1866 elections:

The National situation, so dark before the manifestation given by the people in October and November last of their determination that the Government of the United States should not be administered in the interest of the rebels who tried to overthrow it, is now steadily improving. Loyalty maintains the ascendancy in Congress, endorsed by the people of the Nation with marked unanimity. …

No word of cheer, however applies to our very properly unrecognized State[,] Alabama.

But for the loyalty before alluded to, which manifests so much power at a distance, the personal safety of the loyal men of Alabama might well be questioned. The late devotees to treason have far too much power to permit a loyal man to be regarded with respect by the masses in their train. The pains taken in all places of public resort to denounce the Government and its defenders; the manner in which a vicious press alludes to our flag; the continual annoyance of those who wear the National uniform in either service; the misrepresentations of a Bureau instituted to secure the colored man justice, and which has not been allowed to secure him that justice; and the ingratitude towards the Government in view of its lavish charity dispensed to suffering whites; all indicate that old things have not yet passed away – that treason is still a power in Alabama. …

The missive described several ways in which the freed people were being mistreated and said “that the old pro-slavery ideas, in which [treason] had its birth, have still controlling power in the State.”

And yet we say to you, our loyal brethren, take courage. The power which has made treason stagger, can make it die.

We desire that you keep bright the council fires, and see that the fact that positive loyalty still exists within our borders, is kept before the people, in season, and when the faint hearted would deem out of season. …

The loyal members were to promote the Constitutional amendments and the test oath. They were to clean up their own acts by abolishing “the spirit of hatred and contempt” toward the freed people. The whole world was moving toward greater liberty and justice. The United States federal government was going to make sure that the freedmen were treated with equal rights.

It is your duty then, brethren, in view of this fact – if from no higher consideration – to discard the prejudices of the past against race and color. We would that nobler motives than those of policy might influence you, because even-handed justice is more potent and creditable as an incentive than the lower maxims of the mere politician – But if you will not be constrained by these higher impulses, heed the reasoning of sound policy[.] In the nature of things, the black man is your friend. In the war, the loyal men of the nation found nothing but kindness and respect on his part. He loved the land which we love, and he suffered privation and death in behalf of the cause to us so dear. Shall we have him for our ally, or the rebel for our master?

Trifle not with his friendship by denying him the rights to which he is justly entitled … [including the right to vote.]

Be strong, then, in the love of truth. Seek not to increase your numbers unless the numbers can be increased and the principles here enunciated be maintained at the same time.

Do this, and we will shortly be able to prove before the nation the falsity of the charge now made by rebels, that the loyal men of Alabama have not the ability to manage the State.

Do this, and we will be able to show before God and man, that we have not been unfaithful to the high trust committed to our care.

Done at the Council Chamber in the City of Montgomery, Alabama, on the 2nd day of January, 1867, and the Sixth year of the League.

According to the Encyclopedia of Alabama, the Union League of Alabama “run locally by Freedmen’s Bureau agents and various pro-Union groups, mobilized labor protests and promoted voter registration. The Union League helped create the Reconstruction movement, and it established a tradition of black voting for the Republicans that lasted well into the twentieth century.” The Alabama League started the northern hill country. “League branches sprang up in these areas when former draft resisters and native-born Union veterans found themselves a besieged minority after ex-Confederate soldiers returned to their homes. The league also provided a forum for opponents of Presidential Reconstruction, especially those inclined to organized self-defense, and played an integral role in the passage of military Reconstruction in 1867.”

According to Walter L. Fleming’s 1905 Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama, it was difficult for some white members of the League to get over their prejudices:

Extension to the South

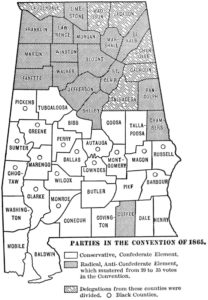

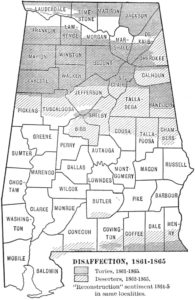

Even before the end of the war the Federal officials had established the organization in Huntsville, Athens, Florence, and other places in north Alabama. It was understood to be a very respectable order in the North, and General Burke, and later General Crawford, with other Federal officers and a few of the so-called “Union” men of north Alabama, formed lodges of what was called indiscriminately the Union or Loyal League. At first but few native whites were members, as the native “unionist” was not exactly the kind of person the Federal officers cared to associate with more than was necessary. But with the close of hostilities and the establishment of army posts over the state, the League grew rapidly. The civilians who followed the army, the Bureau agents, the missionaries, and the northern school-teachers were gradually admitted. The native “unionists” came in as the bars were lowered, and with them that element of the population which, during the war, especially in the white counties, had become hostile to the Confederate administration. The disaffected politicians saw in the organization an instrument which might be used against the politicians of the central counties, who seemed likely to remain in control of affairs. At this time there were no negro members, but it has been estimated that in 1865, 40 per cent of the white voting population in north Alabama joined the order, and that for a year or more there was an average of half a dozen “lodges” in each county north of the Black Belt. Later, the local chapters were called “councils.” There was a State Grand Council with headquarters at Montgomery, and a Grand National Council with headquarters in New York. The Union League of America was the proper designation for the entire organization.

The white members were few in the Black Belt counties and even in the white counties of south Alabama, where one would expect to find them. In south Alabama it was disgraceful for a person to have any connection with the Union League; and if a man was a member, he kept it secret. To this day no one will admit that he belonged to that organization. So far as the native members were concerned, they cared little about the original purposes of the order, but hoped to make it the nucleus of a political organization; and the northern civilian membership, the Bureau agents, preachers, and teachers, and other adventurers, soon began to see other possibilities in the organization.

From the very beginning the preachers, teachers, and Bureau agents had been accustomed to hold regular meetings of the negroes and to make speeches to them. Not a few of these whites expected confiscation, or some such procedure, and wanted a share in the division of the spoils. Some began to talk of political power for the negro. For various purposes, good and bad, the negroes were, by the spring of 1866, widely organized by their would-be leaders, who, as controllers of rations, religion, and schools, had great influence over them. It was but a slight change to convert these informal gatherings into lodges, or councils, of the Union League. After the refusal of Congress to recognize the Restoration as effected by the President, the guardians of the negro in the state began to lay their plans for the future. Negro councils were organized, and negroes were even admitted to some of the white councils which were under control of the northerners. The Bureau gathering of Colonel John B. Callis of Huntsville was transformed into a League. Such men as the Rev. A. S. Lakin, Colonel Callis, D. H. Bingham, Norris, Keffer, and Strobach, all aliens of questionable character from the North, went about organizing the negroes during 1866 and 1867. Nearly all of them were elected to office by the support of the League. The Bureau agents were the directors of the work, and in the immediate vicinity of the Bureau offices they themselves organized the councils. To distant plantations and to country districts agents were sent to gather in the embryo citizens. In every community in the state where there was a sufficient number of negroes the League was organized, sooner or later. In north Alabama the work was done before the spring of 1867; in the Black Belt and in south Alabama it was not until the end of 1867 that the last negroes were gathered into the fold.

The effect upon the white membership of the admission of negroes was remarkable. With the beginning of the manipulation of the negro by his northern friends, the native whites began to desert the order, and when negroes were admitted for the avowed purpose of agitating for political rights and for political organization afterwards, the native whites left in crowds. Where there were many blacks, as in Talladega, nearly all of the whites dropped out. Where the blacks were not numerous and had not been organized, more of the whites remained, but in the hill counties there was a general exodus. Professor Miller estimates that five per cent of the white voters in Talladega County, where there were many negroes, and 25 per cent of those in Cleburne County, where there were few negroes, remained in the order for several years. The same proportion would be nearly correct for the other counties of north Alabama. Where there were few or no negroes, as in Winston and Walker counties, the white membership held out better, for in those counties there was no fear of negro domination, and if the negro voted, no matter what were his politics, he would be controlled by the native whites. What the negro would do in the black counties, the whites in the hill counties cared but little. The sprinkling of white members served to furnish leaders for the ignorant blacks, but the character of these men was extremely questionable. The native element has been called “lowdown, trifling white men,” and the alien element “itinerant, irresponsible, worthless white men from the North.” Such was the opinion of the respectable white people, and the later history of the Leaguers has not improved their reputation. In the black counties there were practically no white members in the rank and file. The alien element, probably more able than the scalawag, had gained the confidence of the negroes, and soon had complete control over them. The Bureau agents saw that the Freedmen’s Bureau could not survive much longer, and they were especially active in looking out for places for the future. With the assistance of the negro they had hoped to pass into offices in the state and county governments. …