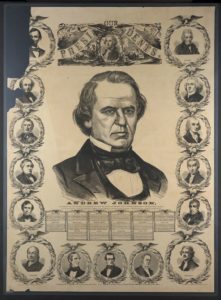

150 years ago this week President Andrew Johnson delivered his second annual message to Congress. Despite the overwhelming Republican victory in Northern states in the 1866 midterm elections, President Johnson did not alter his position: Southern states should be readmitted to the Union and representation in Congress regardless of whether or not the state ratified the would be Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Here’s one Northern newspaper’s view, from The New-York Times of December 4, 1866:

The President’s Message.

President Johnson’s Message has the merit of comparative brevity. It discusses the aspect of the restoration question, embodies the salient points of the Departmental reports, offers suggestions on minor matters of practical legislation, and glances at our foreign relations – all with moderation and good temper, though not with uniform good taste.

On the exciting question of the day – the restoration of the Southern States and the relation of the Executive to Congress – the President has disappointed those who anticipated a change of tone or position. He has neither modified his views not [sic] given any indication of a readiness to concede aught of principle or policy to the demands of the governing States or Congress. He reviews the bearings of the question precisely as he reviewed them more than once during the last session. … He urges the immediate admission of “loyal members from the now unrepresented States” as a measure “imperatively demanded by every consideration of national interest, sound policy, and equal justice.” And he appeals to maxims of WASHINGTON, JEFFERSON and JACKSON to show that the course he recommends is in conformity with the lessons of illustrious statesmen.

It will be seen that the President offers nothing new. His statement of the case is a reiteration of the statement heard many times within the last nine months; his arguments have all been used before; and his recommendation is chiefly noticeable as evidence that he has learned nothing from the elections, and forgotten nothing in connection with his struggle with Congress. The pending Constitutional Amendment is not noticed in the Message, though of course the tenor of the whole argument is adverse to the principle on which the measure rests, and the purposes it is intended to serve. Negro suffrage, universal or qualified, is passed over untouched, and there is not the remotest allusion to an amnesty. In no respect does the President attempt to meet, or even indirectly to recognize, the recent manifestations of public opinion throughout the States which elevated him to office. On the contrary, he explicitly declares that his “convictions heretofore expressed, have undergone no change,” and that “their correctness has been confirmed by reflection and time.”

This exhibition of unyielding purpose on the part of the President may not occasion surprise to those who know the firmness of will which marks his character. We cannot but consider it, however, a serious error of judgment, and a source of difficulty which we would gladly have seen adverted in the session now opened. It has suited the Democratic Press to belittle the significance of the recent elections; but only something a little short of judicial blindness can have led Mr. JOHNSON to rely upon the Democratic rendering of popular opinion. He, of all men, should be able to estimate correctly the import of the verdict pronounced at the polls. He cannot complain of having been misrepresented or misunderstood. He was the exponent of his own case – the active, energetic champion of his own cause. He submitted his policy, in contradistinction to the policy of Congress, to the people of the North and West, everywhere avowing confidence in the rectitude of their intentions and in the sagacity of their judgment. When they decided against him, therefore, – when they repudiated his policy and ranged themselves on the side of Congress – it became his duty, not indeed to abandon his convictions, but to accept the will of the people as the law of his Administration, and either to withdraw all opposition to the Congressional plan, or to propose some new basis of adjustment. By neglecting to pursue one or the other of these courses he has lost the last opportunity of effecting a reconciliation with the great majority of the party that elected him, and has furnished a weapon to his adversaries which they wield to his detriment.

The South, already obstinate to the verge of insolence, will plead the weight of the Executive example. North Carolina has just exemplified its fitness for restoration by electing a conspicuous rebel, Judge MANLY, to the Senate. Alabama has illustrated its abounding loyalty by choosing as United States Senator another conspicuous rebel – Ex-Governor WINSTON. Texas testifies to its acceptance of the situation by tolerating – according to Gen. SHERIDAN – the killing of freedmen as of no more moment than the killing of dogs. And this state of things, bad as it is, and widespread as it seems to be, will grow worse under the influence of the feeling that the President is on the Southern side, and is fighting Congress in their behalf.

The Radicals in Congress, meanwhile, are not slow to avail themselves of the pretext which the Message affords them. … How much further the attack upon his position may be carried, we venture not to prophesy. Enough that this renewal of the argument against the policy of Congress will assuredly be used to feed and intensify a most disastrous conflict of authority. …

According to Hans L. Trefousse, Andrew Johnson didn’t always prioritize state representation in Congress. In 1841 the Tennessee state legislature had to elect two U.S. senators. The Whigs would have controlled the joint session. Andrew Johnson, as a first-term state senator, joined twelve other Democrats who prevented the election of two Whigs by not showing up for a vote. Without a quorum no one was elected to the federal senate. The way I’m reading Wikipedia: Tennessee was completely unrepresented for about a year and a half until October 1843.[1] It wouldn’t have seemed to work out that well for the Immortal Thirteen in the long run: “No senators were elected before the session’s adjournment, and Tennessee remained unrepresented in the U.S. Senate for two years. The controversy proved a major liability for Democrats in the 1843 state elections, in which Whigs won control of both chambers and subsequently elected Ephraim Foster and Spencer Jarnigan to the U.S. Senate.”

From the Library of Congress: seventeenth; Carol M. Highsmith’s photograph of the three native North Carolinians

- [1]Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & company, Inc., 1997. Print. page 46-47.↩