The seventh Thanksgiving since Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States. President Andrew Johnson unobstreperously followed Mr. Lincoln’s example by proclaiming a national commemoration. According to an editorial in The New-York Times all the states went along, except for Mississippi, whose citizens were “called to observe a fast and not a feast.” Another Times article that Richmond, the ex-Confederate capital, observed Thanksgiving with most shops being closed. Henry Ward Beecher delivered another Thanksgiving sermon at Plymouth Church, just as he did in 1860. The Times covered many of the sermons in the metropolitan area, including one from a Unitarian church in Manhattan.

From The New-York Times November 30, 1866:

The American Mind Under Six Years’ Schooling.

DISCOURSE IN THE CHURCH OF THE MESSIAH BY REV. SAMUEL OSGOOD.

For God has not given us the Spirit of peace [sic], but of power, and of love, and of a sound mind – 2d Epistle of Timothy, 1st chapter, 7th verse.

The six years since November, 1860, have been the most memorable period in the history of America – more memorable even than the six years after the Declaration of Independence, in 1776 – since they have established the idea of that Declaration in its true meaning upon a new and immense domain, and alike in the face of home-insurrection and foreign hostility. Compare our position and temper when we met for worship Thanksgiving Day, 1860, and now. The election of President had passed, and the choice of the people called ABRAHAM LINCOLN to the seat of Government. It was generally supposed that the States in the minority would peacefully, although reluctantly, acquiesce in the decision. Alas! we little knew what was in store for us, and we turned away with incredulity, and almost with contempt, from the few, dark prophets who pointed out to us the cloud no bigger than a man’s hand that was to swell into a fearful storm and break with fury upon the land. The speaker here gave some statistics showing that the country was by far more prosperous now than at any time previous to the war. The war had educated the American mind, given it experience, and rendered it practical in all things. He continued: It is hard to say what man best expresses the national idea, or embodies the American mind. We have had no WASHINGTON, HAMILTON or MADISON to guide us from the beginning, or even to tell us what was to happen. We had to make our own way, often in the dark, and our most conspicuous man was a learner like the rest of us; and honest ABRAHAM LINCOLN was willing to take his primer of patriotism and go to God’s school to learn what to do and say. He learned his lesson and said it to the people, and then died, struck by a foul hand that wrote its own doom, and the doom of its rebel crew, and turned the victim, who was sometimes the doubting patriot, into the triumphant martyr. We have had no great leader, and God means that the nation shall be great, and that the American mind itself shall be imperial, and shall need no one chief to imperil its dignity and perhaps tempt it to idolatry. Noble men we have, indeed, who have helped build up the national mind – perhaps, preachers, merchants, poets, journalists, orators, statesmen, philosophers – but the American mind is greater than them all, and follows the call of God and His providence, no matter what a President or Secretary of State, a popular preacher or a noted editor may say. The American mind has learned wisdom of God, and can say with confidence, “God hath not given us the spirit of fear, but of love, and of power, and of a sound mind.” The muscular force of the American mind tells upon its judgment, and our people judge of men and things not by the doctrinaire, but by the dynamic scale. They have been so often disappointed by mere professors, and have tried so many men, and found them wanting, that they have learned to be very discriminating, and to distinguish between the substance and the show. We ask now what a man really is and really can do, and wish to give fair play to every man, without expecting perfection from any. It is remarkable how shrewd our people are, and also how considerate. It is true that they do not mean to run into any extremes, or play the fool with zealots of any faction, or to run into the arms of sectionalists of either type. We mean to work out the problem of peace as we work out the problem of war, by wanting God’s will and doing our best as time called. The nation evidently expected to follow the lead of the President to speedy reconstruction, but they were disappointed in his temper and policy,especially in his veto of the Civil Rights Bill, and his somewhat greater disposition to fraternize with some of the old enemies of emancipation than with its friends. They are sorry that he loses his temper and dignity sometimes, and talks more vehemently than is well. Yet they give him his due and do not think that he meant to betray the old flag, little as he knows its highest worth. They take him as he is and hope to see him learn wisdom and calmness by disappointment. The party of conservative reconstruction was damaged, if not ruined, by the President’s undignified tour; and the party of progressive reconstruction may be sure of the same fate if they make the new apostle of impeachment their organ, and offend the common sense of the country by mistaking a smart lawyer or a staunch Provost-Marshal for a good General or a great statesman. The American mind has learned to like words less and deeds more. It looks with little satisfaction upon blatant orators of the stump or platform, and seems most pleased at present with that quiet man who, after doing the great thing that was to be done to make peace, and giving the order that finished the war, shut his mouth, and showed mainly by his lighted cigar that there was breath still in him and some fire too. The reverend gentleman continued at great length to illustrate how the events of the past six years had educated the American mind to rely upon itself, drawing its ideas of right and justice directly from God, and that those principles actuated it at all times. Speaking of the freedmen, he said: We are putting the dynamic estimate upon classes as well as persons. We have come to the conclusion that we all weigh something, and no useful class can be spared. The millions emancipated by the war – our freed people – are weighed and found not wanting. In 1860 they worked and gave the South its wealth and the North most of its trade. Since 1860 they have fought, and now, all free, they are mostly at work, and many of them and their children, thank God, are at school. They are free and intensely national in their feelings, and, with God’s grace, the great American mind is at work upon them and with them. Fair play for the freedmen in all respects and free suffrage – impartial, intelligent suffrage, for all our people of every hue and blood. Impartial suffrage – the ballot to all who know how to use it, but no ballot to idiots, dunces or sots, black or white.

President Johnson’s proclamation was filled with respectful references to God. According to Hans L. Trefousse, Andrew Johnson, as a young Tennessee legislator in about 1840, “successfully moved to postpone a resolution calling for daily prayers to open legislative proceedings.”[1]

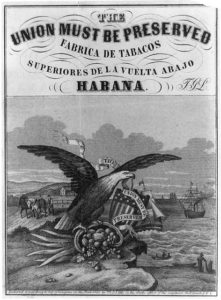

From the Library of Congress: advertisement; Eastman Johnson’s young Abe Lincoln

- [1]Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & company, Inc., 1997. Print. page 41.↩