From a Seneca County, New York newspaper probably in 1866:

FANATICS IN COUNCIL. – A so-called Equal Rights Convention was held at Rochester, on Tuesday and Wednesday last, at which a strolling company of mountebank performers, half male and half female, who favor negro suffrage, woman’s rights, and all the other pernicious isms of the day, appeared. Parker Pillsbury, the negro Redmund [sic], Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and one or two other unsexed women, amused the small audience present.

I don’t think the event was held in Rochester. According to November 21, 1866 issue of The New-York Times, the convention, with between 250 and 300attendees, was held in Albany, New York on November 19th-21st. Lucy Stone was the president of the convention. All the people mentioned in the Seneca County article attended, along with Frederick Douglass:

… Special Dispatch to the New-York Times

ALBANY, Tuesday, Nov. 20, 1866.

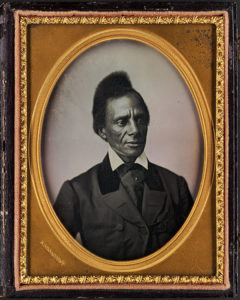

A call for a Convention of those who favor the rights of all persons to equal privileges in the eye of the law was held in Tweddle Hall, in this city, yesterday, and its sessions will continue through tomorrow. The old and shining lights of the anti-slavery rostrum, and the itinerent [sic] lecturers on womens’ rights were there, each and all ready with a panacea for the disordered condition of the country, and predicting a reign of peace and plenty when their suggestions should be heard. It will not be too much, probably, to say that FREDERICK DOUGLASS was the most distinguished in the gathering. He made a speech in his usual close and logical style, or in what his admirers term so, which was received with loud applause. …

SPEECH OF FREDERICK DOUGLASS

FREDERICK DOUGLASS, being called on, said that he had not expected to speak, yet he was always prepared, and would comply with their requests. He had marveled that men had attempted to carry on the fabric of Government without calling in the assistance of women. He affirmed that it was impossible to think of any reason why man should construct a Government which would not apply equally to woman. We do not need government because we are men and women, but because we are human beings, capable of determining between right and wrong, and influenced by good and evil motives. All this, and more, applies to woman as well as to man, and there is not an argument which does not bear with equal weight for both. Our republican form of government is often spoken of as a masterly and unsurpassed specimen of workmanship, provided with checks and balances, which would insure its working right, and to which there is no other Government to be compared. I admit this in part, but not wholly, for there is a partial failure in that part which deprives woman of the franchises of freedom. It appeared to him that this was to be a Woman’s Rights Convention, instead of an Equal Rights Convention. He should not object to this if the women would only kindly take the negro by the hand and elevate him. For his part, he could not attend a public meeting without bringing the negro with him – in fact, he was inseparable. While he thought that the question of equal rights was of importance to women, he thought it was much more so to them. It was a question of life and death, for New-Orleans was remembered by them. Women have a hold on the affections of men, but his race had none on that of the ex-slaveholders. They disliked the black men, and it was therefore essential that they should have the power to vote. Women, if they get the power of voting, will raise the negro, and check the ravages of intemperance and degradation. They say, if woman votes, she will be indifferent to her household duties, and that she will be a mere echo of her husband. He denied this. The wife will look as tenderly on her babe as if she had not voted, and her duties as wife will be as well discharged. He did not see why she should not go with her husband to deposit a ballot, as well as to go to the Post-Office. If she commits a crime, she is punished like any other criminal, and she should have the rights of a citizen. If there was any objection in the minds of persons listening, he hoped to hear from them. He thought if the Convention which nominated LINCOLN and JOHNSON had been composed in part of women, the whole of that nomination would not have been made. …

So women could have saved the country from Andrew Johnson, who was showing himself to be opposed to freedmen aspirations. In a February 1866 meeting President Johnson told Mr. Douglass that he opposed black suffrage. According to Hans L. Trefousse, the president’s official mouthpiece, the Washington National Intelligencer, condemned the September 1866 Southern Loyalists’ Convention in Philadelphia for “welcoming Frederick Douglass. It was the first time a great party had practically carried out the theories of Negro equality,” even though the white race always considered itself superior. “It was obvious that Johnson shared this sentiment, and presumably few blacks or their supporters were taken in by his efforts to appear as their friend.” [1]

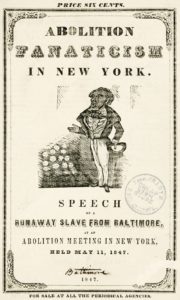

Abolitionism was certainly an ism that shook things up in the 19th century. Project Gutenberg provides a speech Frederick Douglass delivered in 1847. Here’s a paragraph:

…I cannot agree with my friend Mr. Garrison in relation to my love and attachment to this land. I have no love for America, as such; I have no patriotism. I have no country. What country have I? The Institutions of this country do not know me—do not recognize me as a man. I am not thought of, spoken of, in any direction, out of the Anti-Slavery ranks, as a man. I am not thought of or spoken of, except as a piece of property belonging to some Christian Slaveholder, and all the Religious and Political Institutions of this Country alike pronounce me a Slave and a chattel. Now, in such a country as this I cannot have patriotism. The only thing that links me to this land is my family, and the painful consciousness that here there are 3,000,000 of my fellow creatures groaning beneath the iron rod of the worst despotism that could be devised even in Pandemonium,—that here are men and brethren who are identified with me by their complexion, identified with me by their hatred of Slavery, identified with me by their love and aspirations for Liberty, identified with me by the stripes upon their backs, their inhuman wrongs and cruel sufferings. This, and this only, attaches me to this land, and brings me here to plead with you, and with this country at large, for the disenthrallment of my oppressed countrymen, and to overthrow this system of Slavery which is crushing them to the earth. How can I love a country that dooms 3,000,000 of my brethren, some of them my own kindred, my own brothers, my own sisters, who are now clanking the chains of Slavery upon the plains of the South, whose warm blood is now making fat the soil of Maryland and of Alabama, and over whose crushed spirits rolls the dark shadow of Oppression, shutting out and extinguishing forever the cheering rays of that bright Sun of Liberty, lighted in the souls of all God’s children by the omnipotent hand of Deity itself? How can I, I say, love a country thus cursed, thus bedewed with the blood of my brethren? A Country, the Church of which, and the Government of which, and the Constitution of which are in favor of supporting and perpetuating this monstrous system of injustice and blood? I have not, I cannot have, any love for this country, as such, or for its Constitution. I desire to see it overthrown as speedily as possible and its Constitution shivered in a thousand fragments, rather than this foul curse should continue to remain as now. [Hisses and cheers.] …