Way back in April 1866 and probably at least in part responding to President Johnson’s February 19th veto of the Freedmen’s Bureau bill and his belligerent attitude in a Washington’s Birthday message, a The Atlantic Monthly, VOL. XVII.—APRIL, 1866—NO. 102 severely criticized the president and argued that Congress was a more legitimate representative of the people because Congressmen were more directly elected by the people.

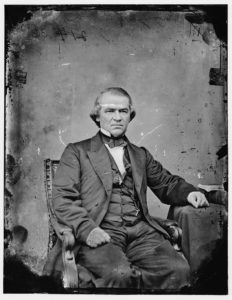

In an issue from 150 years ago this month and undoubtedly published even before Andrew Johnson’s damaging Swing Around the Circle, the periodical continued its attack as the 1866 elections drew near. The article is about 4600 words. Here are a few extracts from The Atlantic Monthly, VOL. XVII.—SEPTEMBER, 1866—NO. CVII:

THE JOHNSON PARTY.

The President of the United States has so singular a combination of defects for the office of a constitutional magistrate, that he could have obtained the opportunity to misrule the nation only by a visitation of Providence. Insincere as well as stubborn, cunning as well as unreasonable, vain as well as ill-tempered, greedy of popularity as well as arbitrary in disposition, veering in his mind as well as fixed in his will, he unites in his character the seemingly opposite qualities of demagogue and autocrat, and converts the Presidential chair into a stump or a throne, according as the impulse seizes him to cajole or to command. Doubtless much of the evil developed in him is due to his misfortune in having been lifted by events to a position which he lacked the elevation and breadth of intelligence adequately to fill. He was cursed with the possession of a power and authority which no man of narrow mind, bitter prejudices, and inordinate self-estimation can exercise without depraving himself as well as injuring the nation. Egotistic to the point of mental disease, he resented the direct and manly opposition of statesmen to his opinions and moods as a personal affront, and descended to the last degree of littleness in a political leader,—that of betraying his party, in order to gratify his spite. He of course became the prey of intriguers and sycophants,—of persons who understand the art of managing minds which are at once arbitrary and weak, by allowing them to retain unity of will amid the most palpable inconsistencies of opinion, so that inconstancy to principle shall not weaken force of purpose, nor the emphasis be at all abated with which they may bless to-day what yesterday they cursed. Thus the abhorrer of traitors has now become their tool. Thus the denouncer of Copperheads has now sunk into dependence on their support. Thus the imposer of conditions of reconstruction has now become the foremost friend of the unconditioned return of the Rebel States. Thus the furious Union Republican, whose harangues against his political opponents almost scared his political friends by their violence, has now become the shameless betrayer of the people who trusted him. And in all these changes of base he has appeared supremely conscious, in his own mind, of playing an independent, a consistent, and especially a conscientious part.

Indeed, Mr. Johnson’s character would be imperfectly described if some attention were not paid to his conscience, the purity of which is a favorite subject of his own discourse, and the perversity of which is the wonder of the rest of mankind. As a public man, his real position is similar to that of a commander of an army, who should pass over to the ranks of the enemy he was commissioned to fight, and then plead his individual convictions of duty as a justification of his treachery. …

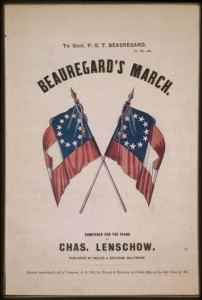

The party which, under the ironical designation of the National Union Party, now proposes to take the policy and character of Mr. Johnson under its charge, is composed chiefly of Democrats defeated at the polls, and Democrats defeated on the field of battle. The few apostate Republicans, who have joined its ranks while seeming to lead its organization, are of small account. Its great strength is in its Southern supporters, and, if it comes into power, it must obey a Rebel direction. …

In the minority Report of the Congressional Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which is designed to supply the new party with constitutional law, this theory of State Rights is most elaborately presented. The ground is taken, that during the Rebellion the States in which it prevailed were as “completely competent States of the United States as they were before the Rebellion, and were bound by all the obligations which the Constitution imposed, and entitled to all its privileges”; and that the Rebellion consisted merely in a series of “illegal acts of the citizens of such States.” On this theory it is difficult to find where the guilt of rebellion lies. The States are innocent because the Rebellion was a rising of individuals; the individuals cannot be very criminal, for it is on their votes that the committee chiefly rely to build up the National Union Party. …

In fact, all attempts to discriminate between Rebels and Rebel States, to the advantage of the latter, are done in defiance of notorious facts. If the Rebellion had been merely a rising of individual citizens of States, it would have been an insurrection against the States, as well as against the Federal government, and might have been easily put down. In that case, there would have been no withdrawal of Southern Senators and Representatives from Congress, and therefore no question as to their inherent right to return. …

The doctrine of the unconditional right of the Rebel States to representation being thus a demonstrated absurdity, the only question relates to the conditions which Congress proposes to impose. Certainly these conditions, as embodied in the constitutional amendment which has passed both houses by such overwhelming majorities, are the mildest ever exacted of defeated enemies by a victorious nation. … [The 14th amendment sent to the states earlier in 1866 for ratification is a moderate, non-radical proposal] …

But whatever view may be taken of the President’s designs, there can be no doubt that the safety, peace, interest, and honor of the country depend on the success of the Union Republicans in the approaching elections. The loyal nation must see to it that the Fortieth Congress shall be as competent to override executive vetoes as the Thirty-Ninth, and be equally removed from the peril of being expelled for one more in harmony with Executive ideas. The same earnestness, energy, patriotism, and intelligence which gave success to the war, must now be exerted to reap its fruits and prevent its recurrence. The only danger is, that, in some representative districts, the people may be swindled by plausibilities and respectabilities; for when, in political contests, any great villany is contemplated, there are always found some eminently respectable men, with a fixed capital of certain eminently conservative phrases, innocently ready to furnish the wolves of politics with abundant supplies of sheep’s clothing. These dignified dupes are more than usually active at the present time; and the gravity of their speech is as edifying as its emptiness. Immersed in words, and with no clear perception of things, they mistake conspiracy for conservatism. Their pet horror is the term “radical”; their ideal of heroic patriotism, the spectacle of a great nation which allows itself to be ruined with decorum, and dies rather than commit the slightest breach of constitutional etiquette. This insensibility to facts and blindness to the tendency of events, they call wisdom and moderation. Behind these political dummies are the real forces of the Johnson party, men of insolent spirit, resolute will, embittered temper, and unscrupulous purpose, who clearly know what they are after, and will hesitate at no “informality” in the attempt to obtain it. To give these persons political power will be to surrender the results of the war, by placing the government practically in the hands of those against whom the war was waged. No smooth words about “the equality of the States,” “the necessity of conciliation,” “the wickedness of sectional conflicts,” will alter the fact, that, in refusing to support Congress, the people would set a reward on treachery and place a bounty on treason. “The South,” says a Mr. Hill of Georgia, in a letter favoring the Philadelphia Convention, “sought to save the Constitution out of the Union. She failed. Let her now bring her diminished and shattered, but united and earnest counsels and energies to save the Constitution in the Union.” The sort of Constitution the South sought to save by warring against the government is the Constitution which she now proposes to save by administering it! Is this the tone of pardoned and penitent treason? Is this the spirit to build up a “National Union Party”? No; but it is the tone and spirit now fashionable in the defeated Rebel States, and will not be changed until the autumn elections shall have proved that they have as little to expect from the next Congress as from the present, and that they must give securities for their future conduct before they can be relieved from the penalties incurred by their past.