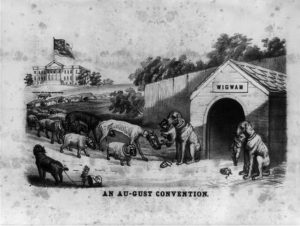

On August 14-17 a National Union Convention was held in Philadelphia. Although a new mega-party of Democrats and moderate Republicans was not achieved, it was hoped that the convention would stir up public support for President Johnson’s lenient Reconstruction policy and lead to victory over Radical Republicans in the 1866 fall elections.The convention was also referred to as the Arm-In-Arm Convention because South Carolina’s Governor James L. Orr and Massachusetts’ General Darius N. Couch walked arm-in-arm as they led a procession of delegates.[1]

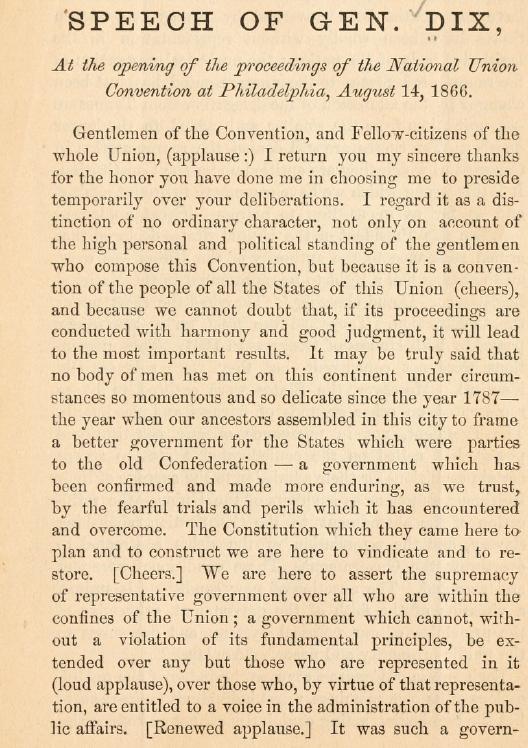

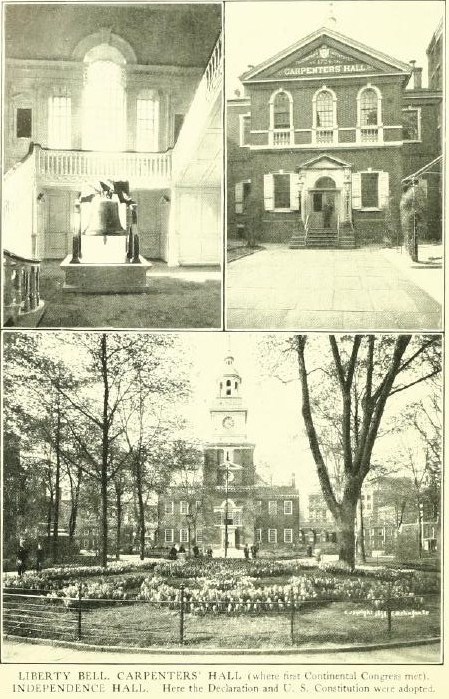

John Adams Dix, who certainly believed in the Union and its banner, delivered the opening speech that compared the meeting with the constitutional Convention of 1787. Here is some of it:

From The Struggle between President Johnson and Congress over Reconstruction by Charles Ernest Chadsey (1896; pages 91-95):

… The fall campaign was formally opened by the supporters of the presidential policy, who had immediately accepted the report of the Committee on Reconstruction as the platform of the Republican anti-administration faction, and had determined to appeal on that issue to the people. Their hope was that the conservative element of the population, thoroughly worn out by the struggle, would uphold the speedy restoration of the Southern States, and that thereby a coalition might be made between the Democrats and the administration Republicans strong enough to unseat many of the radical members, reverse the majority, and so give the administration control in the 40th Congress.

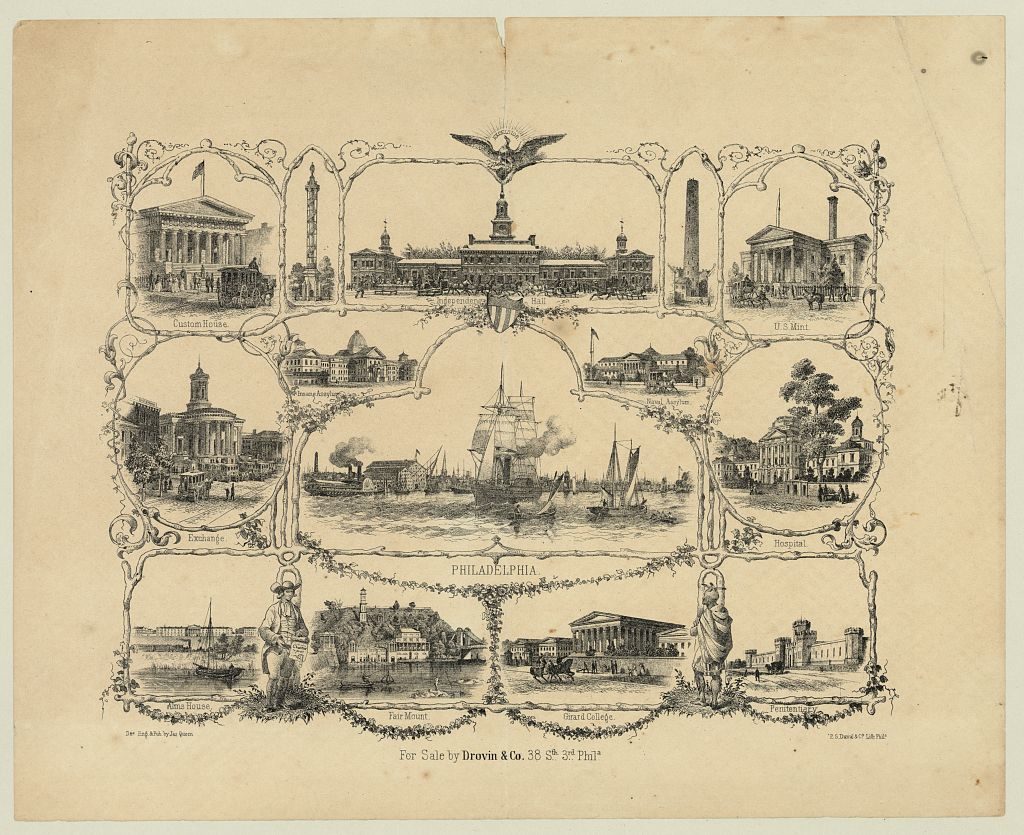

The first steps were promptly taken. The executive committee of the National Union Club, a political organization established in Washington by supporters of the administration, issued on June 25, just one week after the submission of the report of the Committee on Reconstruction, a call for a national convention to be held in Philadelphia on August 14. Delegates to this convention were to be chosen by those supporting the administration and agreeing to certain “fundamental propositions” which formed the platform of the conservatives. These propositions maintained the absolute indissolubility of the Union, the universal supremacy of the Constitution and acts of Congress in pursuance thereof, the constitutional guarantee to maintain the rights, dignity and equality of the States, and the right of each State to prescribe the qualifications of electors, without any federal interference. They declared that the usurpation and centralization of powers infringing upon the rights of the States “would be a revolution, dangerous to republican government, and destructive of liberty;” that the exclusion of loyal senators and representatives, properly chosen and qualified under the Constitution and laws, was unjust and revolutionary; that as the war was at an end, “war measures should also cease, and should be followed by measures of peaceful administration;” and that the restoration of the rights and privileges of the States was necessary for the prosperity of the Union. This formal call was approved, and its principles endorsed by the Democratic congressmen, who issued an address to the “People of the United States” on July 4, urging them to act promptly in the selection of delegates to the convention.

In accordance with the call, every State and Territory was represented in the convention. A glance at the list of delegates shows that they included many of the prominent Democrats of the country, re-enforced by a number of the prominent Republicans who were in sympathy with the administration. The enthusiastic manner in which the summons was answered seemed to the friends of the administration to indicate an unquestionable overthrow of the radicals. They thought that harmony was soon to reign over all portions of the Union, which was once more being drawn closely together by the watchword “National Union.”

Reverdy Johnson, who had submitted in the Senate the minority report of the Committee on Reconstruction, was chosen chairman, and Senator Cowan, of Pennsylvania, chairman of the committee on resolutions. The resolutions were reported on August 17, and unanimously adopted by the convention. They re-affirmed the fundamental principles set forth in the call of June 25, and appealed to the people of the United States to elect none to Congress but those who “will receive to seats therein loyal representatives from every State in allegiance to the United States.” They reiterated the claim that in the ratification of constitutional amendments all the States “have an equal and an indefeasible right to a voice and vote thereon.” In concession to Northern sentiment, they declared that the South had no desire to re-establish slavery; that the civil rights of the freedmen were to be respected, the rebel debt repudiated, the national debt declared sacred and inviolable, and the duty of the government to recognize the services of the federal soldiers and sailors admitted. A final resolution commended the President in the highest terms, as worthy of the nation, “having faith unassailable in the people and in the principles of free government.”

These views were fully elaborated in an address prepared by Henry J. Raymond, and read before the convention. Little attempt was made to qualify or render less offensive the argument that the Southern States must be allowed their representation in Congress, whether or not such action was for the best interest of the Union. Referring to this the address declared that “we have no right, for such reasons, to deny to any portion of the States or people rights expressly conferred upon them by the Constitution of the United States.” We should trust to the ability of our people “to protect and defend, under all contingencies and by whatever means may be required, its honor and welfare.”

A committee of the convention hastened formally to present its proceedings to President Johnson, who had taken the keenest interest in the plans of the National Union party. In his remarks to the committee he feelingly referred to the somewhat theatrical entrance of the delegates of South Carolina and Massachusetts, “arm in arm, marching into that vast assemblage, and thus giving evidence that the two extremes had come together again, and that for the future they were united, as they had been in the past, for the preservation of the Union.” Speaking to a sympathetic audience, who applauded him to the echo, and believing that the people were now endorsing his opposition to Congress, he saw no necessity for tempering his statements, and cast aside his discretion. His characterization of Congress was as follows: “We have witnessed, in one department of the government, every endeavor to prevent the restoration of peace, harmony and union. We have seen hanging upon the verge of the Government, as it were, a body called, or which assumes to be, the Congress of the United States, while in fact it is a Congress of only a part of the States. We have seen this Congress pretend to be for the Union, when its every step and act tended to perpetuate disunion and make a disruption of the States inevitable. Instead of promoting reconciliation and harmony, its legislation has partaken of the character of penalties, retaliation and revenge. This has been the course and policy of one portion of the Government.” Again, to show the disinterestedness of his own course, he said: “If I had wanted authority, or if I had wished to perpetuate my own power, how easily could I have held and wielded that power which was placed in my hands by the measure called the Freedmen’s Bureau bill (laughter and applause). With an army, which it placed at my discretion, I could have remained at the capital of the nation, and with fifty or sixty millions of appropriations at my disposal, with the machinery to be unlocked by my own hands, with my satraps and dependents in every town and village, with the Civil Rights bill following as an auxiliary (laughter), and with the patronage and other appliances of the Government, I could have proclaimed myself dictator.” (“That’s true!” and applause.) …

New York Times editor and New York Congressman Henry J. Raymond delivered the main address at the convention, “but his draft of the platform included guarded praise of the Fourteenth Amendment and oblique criticism of slavery. This proved too much for the Resolutions Committee, which omitted the offending passages.[2]