“The Misses Cooke’s school room, Freedman’s Bureau, Richmond, Va. / from a sketch by Jas. E. Taylor.”

150 years ago this week Congress took almost all of three hours to override a presidential veto

In February 1866 President Andrew Johnson vetoed a bill to extend the jurisdiction of the Freedmen’s Bureau. The U.S. Senate was unable to override the president’s veto. On Washington’s Birthday Mr. Johnson made some incendiary remarks that likened abolitionist Wendell Phillips, Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, and Senator Charles Sumner to traitorous rebels. That changed everything. Congress would eventually pass the Freedmen’s Bureau bill again. On July 16, 1866 President Johnson again sent a veto message to Congress. Both Houses of Congress immediately voted to override the veto. According to the July 17, 1866 issue of The New-York Times Congress received the veto message at 2:00 PM and both Houses had voted to override before 5:00 PM. “Thus the Freedmen’s Bureau is a fixed fact for two years from the 16th of July, 1866.”

You can read President Johnson’s veto message at The American Presidency Project. The president believed that the original 1865 Freedmens’s Bureau act was a war measure, still in operation; it would still be operating for months after the next Congress convened. It was unconstitutional for he federal government to intervene in state matters during peace time. Competent civil courts had been re-established which might conflict with the military tribunals in the South. There had been reports of abuse by Freedmen’s Bureau bureaucrats. The 1866 Civil Rights Act was already providing equal protection to all. President Johnson concluded his message by stating his concern that the federal largesse might produce an idle class:

In conclusion I again urge upon Congress the danger of class legislation, so well calculated to keep the public mind in a state of uncertain expectation, disquiet, and restlessness and to encourage interested hopes and fears that the National Government will continue to furnish to classes of citizens in the several States means for support and maintenance regardless of whether they pursue a life of indolence or of labor, and regardless also of the constitutional limitations of the national authority in times of peace and tranquillity.

The bill is herewith returned to the House of Representatives, in which it originated, for its final action.

ANDREW JOHNSON.

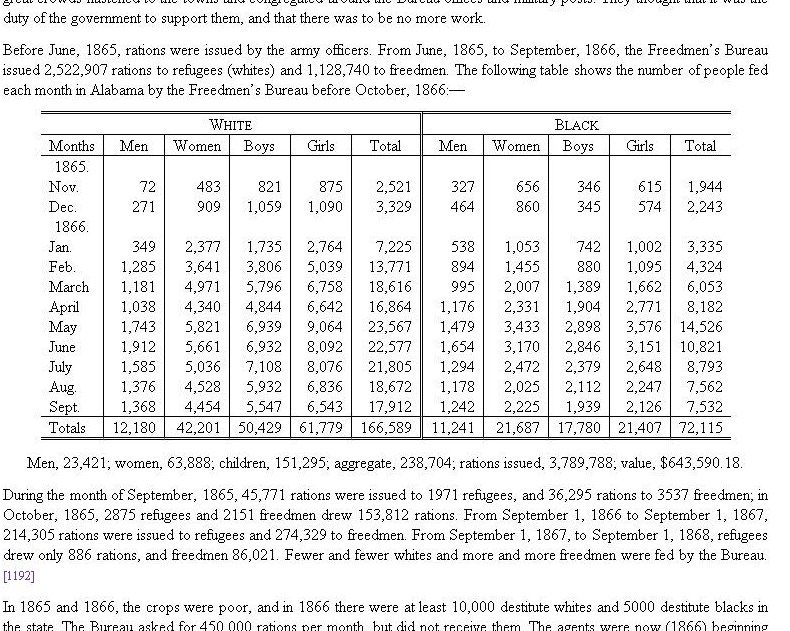

Walter L. Fleming’s 1905 Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama discussed the Freedmen’s Bureau under the heading of “The Wards of the Nation”, but the Bureau also distributed rations to poor white people in Alabama in 1865 and 1866 as can be seen in the following table:

In a U.S. history textbook, John A. Garraty points out that many freed slaves understandably “at first equated legal freedom with freedom from having to earn a living, a tendency reinforced for a time by the willingness of the Freedmen’s Bureau to provide rations and other forms of relief in war-devastated areas. Most, however, soon accepted the fact that they must earn a living …” Southern agricultural output did decrease greatly after the abolition of slavery, not because the freedmen were dependent on their overseers, but because they had their children, women, and old people spend less time in the fields. Some southern whites criticized the decline in output by using racial stereotypes. As it turned out, freed blacks enjoyed more leisure and were better off materially after the war: “Their earnings brought them almost 30 percent more than the value of the subsistence provided by their former masters.” [1]

“Glimpses at the Freedmen’s Bureau. Issuing rations to the old and sick” in Richmond, Virginia (Library of Congress)

- [1]Garraty, John A., and Robert A. McCaughey. The American Nation: A History of the United States, Seventh Edition. New York: HarpersCollins Publishers, 1991. Print.page 461.↩