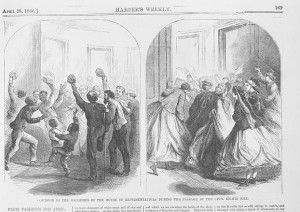

“Outside of the galleries of the House of Representatives during the passage of the civil rights bill” – Library of Congress

April 9, 1866 marked the first anniversary of General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. On that same day the United States House of Representatives overrode President Andrew Johnson’s veto of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. In conjunction with the Senate’s override vote on April 6th this represented “the first time in American history [that] Congress enacted a major piece of legislation over a President’s veto”[1]

Eric Foner explains that President Johnson’s veto of the Civil Rights Bill did not isolate the Radicals – it made moderate Republicans realize that the president’s policies were dangerous for the party, especially since the Civil Rights Act was the right thing to do and naturally followed the Union victory in the war. President Johnson thought he would win on the Civil Rights Bill because racism was “deeply embedded in Northern as well as Southern public life” and because of the importance of individual state sovereignty over local affairs, as Frederick Douglass noted. “Given the Civil Rights Act’s astonishing expansion of federal authority and blacks’ rights, it is not surprising that Johnson considered it a Radical measure and believed he could mobilize voters against it.”[2]

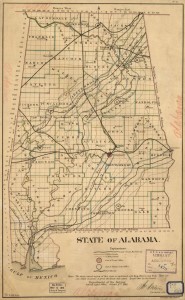

The Civil Rights Bill and Freedmen’s Bill of early 1866 impinged on the embedded racism in Alabama’s public life and on Alabama’s notions of state control over local matters, as Walter L. Fleming’s 1905 Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama pointed out:

New Conditions of Congress and Increasing Irritation

The first general assembly under the provisional government ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, “with the understanding that it does not confer upon Congress the power to legislate upon the political status of freedmen in this state.” The same legislature requested the President to order the withdrawal of the Federal troops on duty in Alabama, for their presence was a source of much disorder and there was no need of them.

The President was asked to release Hon. C. C. Clay, Jr., who was still in prison. At the end of the session a resolution was adopted approving the policy of President Johnson and pledging coöperation with his “wise, firm, and just” work; asserting that the results of the late contest were conclusive, and that there was no desire to renew discussion on settled questions; denouncing the misrepresentations and criminal assaults on the character and interest of the southern people; declaring that it was a misfortune of the present political conditions that there were persons among them whose interests were promoted by false representations; confidence was expressed in the power of the administration to protect the state from malign influences; slavery was abolished and should not be reëstablished; the negro race should be treated with humanity, justice, and good faith, and every means be used to make them useful and intelligent members of society; but “Alabama will not voluntarily consent to change the adjustment of political power as fixed by the Constitution of the United States, and to constrain her to do so in her present prostrate and helpless condition, with no voice in the councils of the nation, would be an unjustifiable breach of faith.”

During the year 1866 there was a growing spirit of independence in the Alabama politics. At no time had there been a subservient spirit, but for a time the people, fully accepting the results of the war, were disposed to do nothing more than conform to any reasonable conditions which might be imposed, feeling sure that the North would impose none that were dishonorable. To them at first the President represented the feeling of the people of the North, perhaps worse. The theory of state sovereignty having been destroyed by the war, the state rights theories of Lincoln and Johnson were easily accepted by the southerners, who were content, after Johnson had modified his policy, to leave affairs in his hands. When the serious differences between the executive and Congress appeared, and the latter showed a desire to impose degrading terms on the South, the people believed that their only hope was in Johnson. They believed the course of Congress to be inspired by a desire for revenge. Heretofore the people had taken little interest in public affairs. Enough voters went to the polls and voted to establish and keep in operation the provisional government. The general belief was that the political questions would settle themselves or be settled in a manner fairly satisfactory to the South. Now a different spirit arose. The southerners thought that they had complied with all the conditions ever asked that could be complied with without loss of self-respect. The new conditions of Congress exhausted their patience and irritated their pride. Self-respecting men could not tamely submit to such treatment.

During the latter part of 1865 and in 1866, ex-Governor Parsons travelled over the North, speaking in the chief cities in support of the policy of the President. He asked the northern people to rebuke at the polls the political fanatics who were inflaming the minds of the people North and South. He demanded the withdrawal of the military. There had been, he said, no sign of hostility since the surrender; the people were opposed to any legislation which would give the negro the right to vote; and it was the duty of the President, not of Congress, to enforce the laws.

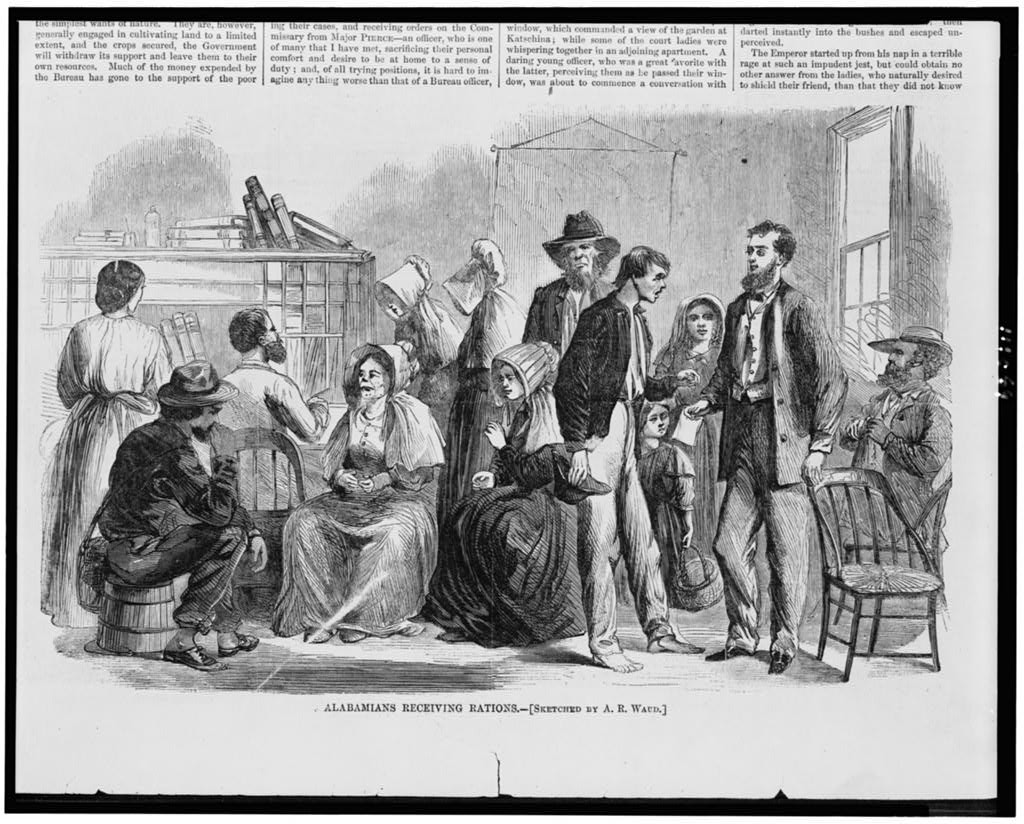

Much angry discussion was caused by the passage of the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill in 1866. The Bureau officials had caused themselves to be hated by the whites. They were a nuisance, when no worse, and useless,—a plague to the people. Though there were comparatively few in the state, they were the cause of disorder and ill-feeling between the races. Though there was now even less need of the institution than a year before, the new measure was much more offensive in its provisions. There was great rejoicing when the President vetoed the bill, which the Mobile Times called “an infamous disorganization scheme of radicalism.” The Bureau had become a political machine for work among white and black. The passage of the bill over the veto was felt to be a blow at the prostrate South.

The Civil Rights Bill of 1866 was also a cause of irritation. There was a disposition among the officials of the Freedmen’s Bureau to enforce all such measures before they became law. Orders were issued directing the application of the principles of measures then before Congress. The United States commissioner in Mobile decided that under the “Civil Rights Bill” negroes could ride on the cars set apart for the whites. Horton, the Radical military mayor of Mobile, banished to New Orleans an idiotic negro boy who had been hired to follow him and torment him by offensive questions. Horton was indicted under the “Civil Rights Bill” and convicted. The people of Mobile were much pleased when a “Yankee official was the first to be caught in the trap set for southerners.”

Another citizen of Mobile, a magistrate, was haled before a Federal court, charged with having sentenced a negro to be whipped, contrary to the provisions of the “Civil Rights Bill.” The magistrate explained that there was nothing at all offensive about the whipping. He had not acted in his magisterial capacity, but had himself whipped the negro boy for lying, stealing, and neglect of duty while in his employ. The agent of the Bureau at Selma notified the mayor that the “chain gang system of working convicts on the streets had to be discontinued or he would be prosecuted for violation of the ‘Civil Rights Bill.’” Judge Hardy of Selma decided in a case brought before him that the “Civil Rights Bill” was unconstitutional. He declared it to be an attack on the independence of the judiciary.

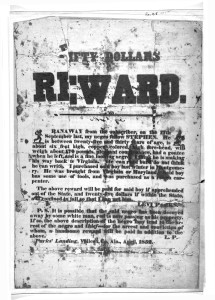

1852: “Poster offering fifty dollars reward for the capture of a runaway slave Stephen.” – Library of Congress

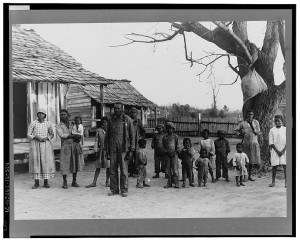

1937: “Negroes, descendants of former slaves of the Pettway Plantation. They are living under primitive conditions on the plantation. Gees Bend, Alabama” – Library of Congress