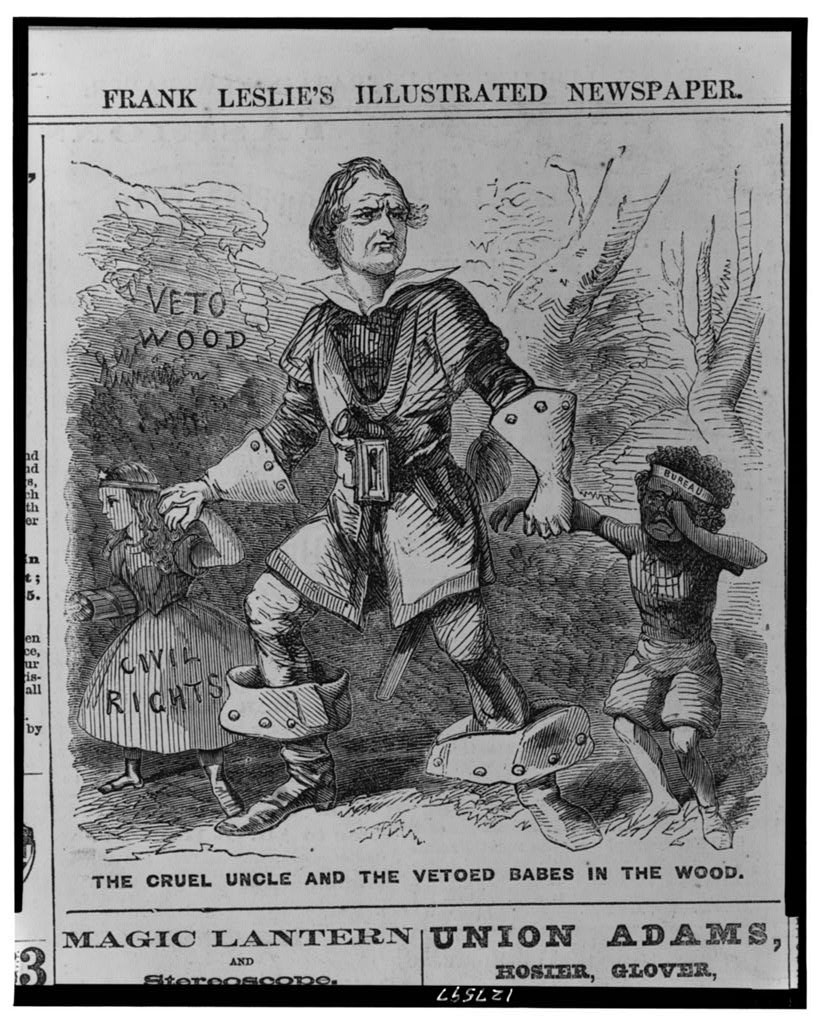

In February 1866 President Andrew Johnson vetoed the Freedmen’s Bureau extension act. On March 27th he vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Here’s an 1896 summary from The Struggle between President Johnson and Congress over Reconstruction by Charles Ernest Chadsey:

6. After the President had thus publicly stigmatized the opponents of his policy as instigators of a new rebellion, and classed Stevens, Sumner and Wendell Phillips as traitors to be compared with Davis, there could be no hope of reconciliation, and the Republican party grimly settled down to fight for its principles. The first important measure to take effect was the civil rights bill.

On the first day of the session Senator Wilson, of Massachusetts, had introduced a bill looking to the personal protection of the freedmen. It was aimed directly at the “black laws” of the Southern States, and declared all laws, statutes, acts, etc., of any description whatsoever, which caused any inequality of civil rights, in consequence of race or color, to be void. In his speech of December 13, 1865, explaining his reasons for introducing the bill, Wilson said that, while honest differences as to the expediency of negro suffrage might exist, he could not comprehend “how any humane, just and Christian man can, for a moment, permit the laws that are on the statute-books of the States in rebellion, and the laws that are now pending before their legislatures, to be executed upon men whom we have declared to be free. * * * To turn these freedmen over to the tender mercies of men who hate them for their fidelity to the country is a crime that will bring the judgment of heaven upon us.”

This bill and a similar bill introduced by the same senator on December 21, and one introduced by Senator Sumner on the first day of the session, never came to a vote, the last two being postponed indefinitely by the Senate. In place of these bills, Senator Trumbull of Illinois, chairman of the Committee on the Judiciary, on January 5, 1866, introduced a bill which, slightly amended, became a law. This measure passed the Senate on February 2, was amended and passed by the House on March 13, and the amendments were concurred in by the Senate on the 15th. It was returned to the Senate by the President, without his approval, March 27, and on April 6 the Senate passed the bill over the veto of the President by a vote of 33 to 15. Three days later the House passed the bill by a vote of 122 to 41, and the measure became a law.

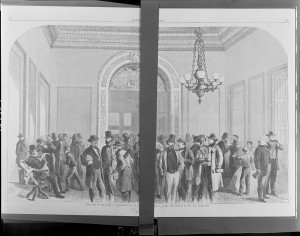

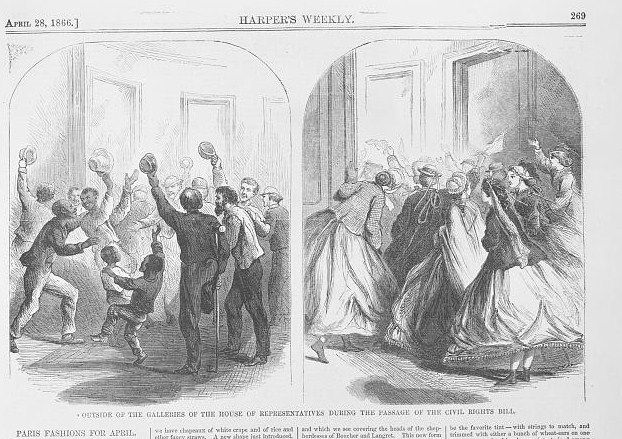

“The lobby of the House of Representatives at Washington during the passage of the civil rights bill” – Library of Congress

As passed it was entitled, “An Act to protect all persons in the United States in their civil rights, and furnish the means of their vindication.” It first declared “all persons born in the United States, and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed,” to be citizens of the United States. Such citizens, without regard to race, color, or previous servitude, were declared to have the same rights in all the States and Territories, as white citizens, to make and enforce contracts; to “sue, be parties, and give evidence; to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property;” to enjoy the equal benefit of all laws for the security of person and property, and to be subject only to the same punishments. The second section provided penalties for the deprivation of equal rights. The third gave to the United States courts exclusive cognizance of all causes involving the denial of the rights secured by the first section. The remaining sections specified the powers and duties of the district attorneys, marshals, deputy marshals and special commissioners, in connection with the enforcement of the act, the ninth section providing: “It shall be lawful for the President of the United States, or such person as he may empower for that purpose, to employ such part of the land or naval forces of the United States, or of the militia, as shall be necessary to prevent the violation and enforce the due execution of the Act.”

From this summary of the act its nature can be seen plainly. Up to this time there had been no legislation affecting the status of the freedman. This declared him to be a citizen of the United States, and thereby entitled to all the privileges of citizenship. The war having resulted in the anomalous condition of the several millions of freedmen, some such legislation was necessary, especially in view of the fact that discriminative legislation was being enacted in the South. The bill was moderate in its terms, the most questionable portion being the section empowering the President to enforce the act through the war department, but even that in the then unsettled condition of the country had much to justify it.

The President’s veto message was a lengthy document and discussed in detail the significance of the bill. He questioned the policy of conferring citizenship on four million blacks while eleven of the States were unrepresented in Congress. He doubted whether the negroes possessed the qualifications for citizenship, and thought that their proper protection did not require that they be made citizens, as civil rights were secured to them as they were, while the bill discriminated against the intelligent foreigner. Naturally, he also declared that the securing by federal law of equality of the races was an infringement upon state jurisdiction. “Hitherto, every subject embraced in the enumeration of rights contained in this bill has been considered as exclusively belonging to the States.” The second section he thought to be of doubtful constitutionality and unnecessary, “as adequate judicial remedies could be adopted to secure the desired end, without invading the immunities of legislators, * * * without assailing the independence of the judiciary, * * * and without impairing the efficiency of ministerial officers. * * * The legislative department of the United States thus takes from the judicial department of the States the sacred and exclusive duty of judicial decision, and converts the State judge into a mere ministerial officer bound to decide according to the will of Congress.” The third section he characterized as undoubtedly comprehending cases and authorizing the “exercise of powers that are not by the Constitution within the jurisdiction of the courts of the United States.” He also considered the extraordinary powers of the numerous officials created by the act as jeopardizing the liberties of the people, and the provisions in regard to fees as liable to bring about persecution and fraud.

In addition to these objections he argued that the bill frustrated the natural adjustment between capital and labor in a way potent to cause discord. It was “an absorption and assumption of power by the General Government which, if acquiesced in, must sap and destroy our federative system of limited powers, and break down the barriers which preserve the rights of the States. * * * The tendency of the bill must be to resuscitate the spirit of rebellion, and to arrest the progress of those influences which are more closely drawing around the States the bonds of union and peace.”

Here is the last part of the president’s veto message from TeachingAmericanHistoryorg:

… I do not propose to consider the policy of this bill. To me the details of the bill are fraught with evil. The white race and black race of the South have hitherto lived together under the relation of master and slave—capital owning labor. Now that relation is changed; and as to ownership, capital and labor are divorced. They stand now, each master of itself. In this new relation, one being necessary to the other, there will be a new adjustment, which both are deeply interested in making harmonious. Each has equal power in settling the terms; and, if left to the laws that regulate capital and labor, it is confidently believed that they will satisfactorily work out the problem. Capital, it is true, has more intelligence; but labor is never ignorant as not to understand its own interests, not to know its own value, and not to see that capital must pay that value. This bill frustrates this adjustment. It intervenes between capital and labor, and attempts to settle questions of political economy through the agency of numerous officials, whose interest it will be to foment discord between the two races; for as the breach widens, their employment will continue; and when it is closed, their occupation will terminate. In all our history, in all our experience as a people living under Federal and State law, no such system as that contemplated by the details of this bill has ever before been proposed or adopted. They establish for the security of the colored race safeguards which go indefinitely beyond any that the General Government has ever provided for the white race. In fact, the distinction of race and color is by the bill made to operate in favor of the colored against the white race. They interfere with the municipal legislation of the States; with relations existing exclusively between a State and its citizens, or between inhabitants of the same State; an absorption and assumption of power by the General Government which, if acquiesced in, must sap and destroy our federative system of limited power, and break down the barriers which preserve the rights of the States. It is another step, or rather stride, towards centralization and the concentration of all legislative powers in the National Government. The tendency of the bill must be to resuscitate the spirit of rebellion, and to arrest the progress of those influences which are more closely drawing around the States the bonds of union and peace.

My lamented predecessor, in his proclamation of the 1st of January, 1863, ordered and declared that all persons held as slaves within certain States and parts of States therein designated, were, and thenceforward should be free; and further, that the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, would recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons. This guaranty has been rendered especially obligatory and sacred by the amendment of the Constitution abolishing slavery throughout the United States. I, therefore, fully recognize the obligation to protect and defend that class of our people whenever and wherever it shall become necessary, and to the full extent, compatible with the Constitution of the United States. Entertaining these sentiments, it only remains for me to say that I will cheerfully co-operate with Congress in any measure that may be necessary for the preservation of civil rights of the freedmen, as well as those of all other classes of persons throughout the United States, by judicial process under equal and impartial laws, or conformably with the provisions of the Federal Constitution.

I now return the bill to the Senate, and regret that in considering the bills and joint resolutions, forty-two in number, which have been thus far submitted for my approval, I am compelled to withhold my assent from a second measure that has received the sanction of both Houses of Congress.

Andrew Johnson

Washington, D.C., March 27, 1866.

The Senate on April 6th and the House on April 9th voted to override President Johnson’s veto. The Civil Rights Act of 1866, which you can read at PBS, became federal law.

“Outside of the galleries of the House of Representatives during the passage of the civil rights bill” – Library of Congress