On February 19, 1866 President Andrew Johnson vetoed the Freedmen’s Bureau Extension bill. Here is a review of commentary from more modern scholars.

Walter Stahr points out that Mr. Johnson vetoed the bill because he agreed with Southern whites who hated the bureau “meddling in their domestic affairs” and with Democrats who disagreed with the expansion of federal power. The president also wanted those groups to support him on the 1868 election. President Johnson asked for draft veto messages from several advisers, including William H. Seward. Mr. Johnson used some of the Secretary of State’s technical arguments, but the main point of the final veto message was that Congress had no power to legislate about reconstruction until all the southern states were represented in Congress[1]

According to Eric Foner, “In appealing to fiscal conservatism, raising the specter of an immense federal bureaucracy trampling on citizen’s rights, and insisting self-help, not dependence on outside assistance, offered the surest road to economic advancement, Johnson voiced themes that to this day have have sustained opposition to federal intervention on behalf of blacks.” The veto intensified the bitterness between President and Congress; apparently because of President Johnson’s insistence on seating southern representatives, William P. Fessenden pointed out that Mr. Johnson “will and must … veto every other bill we pass” concerning Reconstruction. President Johnson sincerely thought that the Bureau was unconstitutional and encouraged the freedmen to be lazy. He underestimated moderate Republican support for “federal protection for freedmen.”[2]

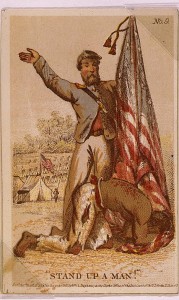

Adam Tuchinsky contrasts the views of two New York newspapers on the Freedmen’s Bureau, which “was the first federal agency charged with caring for the social welfare of citizens; grounded in the idea of social rights, it was naturally quite controversial on ideological grounds.” The New-York Times, which “had been pushing a proto-social Darwinist brand of laissez-faire liberalism for more than a decade,” agreed with President Johnson that Bureau reduced the freed people to an almost childlike dependency. Horace Greeley’s New-York Tribune disagreed because the formerly enslaved had been unable to develop any of the necessary skills for self-reliance: “‘Deplorable necessities of the Blacks result from their life-long subjection to cruel social and political disabilities,’ the Tribune insisted. ‘Give the Blacks their honest due to-day, and they as a race would need none of your alms.'”[3]

![[Horace] Greeley statue, Tribune Office (between ca. 1910 and ca. 1915; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/ggb2005019292/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/19303v-703x1024.jpg)