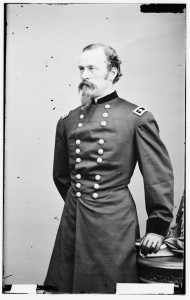

The American Union Commission held a big fundraising event in New York City 150 years ago tonight. Many famous men attended or sent in their regrets. Provisional Alabama Governor Lewis E. Parsons gave a first-hand report from the field. Alabama’s problems intensified during the latter stages of the war when Union troops under General James H. Wilson raided and ransacked parts of Alabama and Georgia. In the war’s aftermath the freed slaves stopped working in the fields, there was a severe drought, and the state was broke. Here’s Governor Parson’s speech:

From The New-York Times November 14, 1865:

SOUTHERN DESTITUTION; Large Public Meeting at Cooper Institute. The Wants and Sufferings of the South Described. Statement and Plea of Governor Parsons of Alabama. The Aims of the American Union Commission. ADDRESS OF REV. HENRY WARD BEECHER Short Speeches of Gen. Meade, Rev. Dr. Thompson and Gen. Fisk. SPEECH OF DR. JOS. P. THOMPSON. SPEECH OF REV. HENRY WARD BEECHER. LETTER FROM SECRETARY SEWARD. ADDRESS OF GEN. FISK.

A meeting in aid of the American Union Commission and its work at the South, was held last night at Cooper Institute, at which time an audience of about two thousand persons attended to listen to addresses from eminent men from both sections of the country.

At 7:30 o’clock, Hon. E.D. MORGAN, Maj.-Gen. MEADE, Rev. HENRY WARD BEECHER, GOV. PARSONS of Alabama, Hon. ABRAM WAKEMAN, Rev. Dr. BACON and other gentlemen entered the hall and were received with hearty cheers. …

Gov. PARSONS was received with expressions of applause. He said:

SPEECH OF GOV. PARSONS, OF ALABAMA.

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN: It is difficult with language to portray the devastation which war, especially civil war, produces, so as to furnish an adequate idea of its effects. To realize them you must witness them; to comprehend them fully you must live upon the theatre and witness the advance and the retreat of vast armies, listen to the roar of battle, and see those who are left upon the field after the retreat; you must see fields laid waste, farm-houses, cotton-presses and gins in ruins; you must see towns and cities in flames to form anything like an adequate idea of what war in reality is. You whose fortune it has been to see only the regiment with colors streaming, the recipients of all the kindness and watchful care that friends could bestow, as they left for the scene of battle, can form no conception of the appearance of that regiment after the battle is over, unless, indeed, it has been your fortune to be on the scene of action or so near it that your house has been crowded with those who have become victims of the strife. It will be in your recollection, ladies and gentlemen, that during the last of March and in April the rebellion suddenly collapsed. At that time public attention in the North was doubtless turned mainly to the operations around Richmond, and to those which attended the movements of the vast armies of Gen. SHERMAN.

“Portrait of Maj. Gen. (as of May 6, 1865) James H. Wilson, officer of the Federal Army” (Library of Congress)

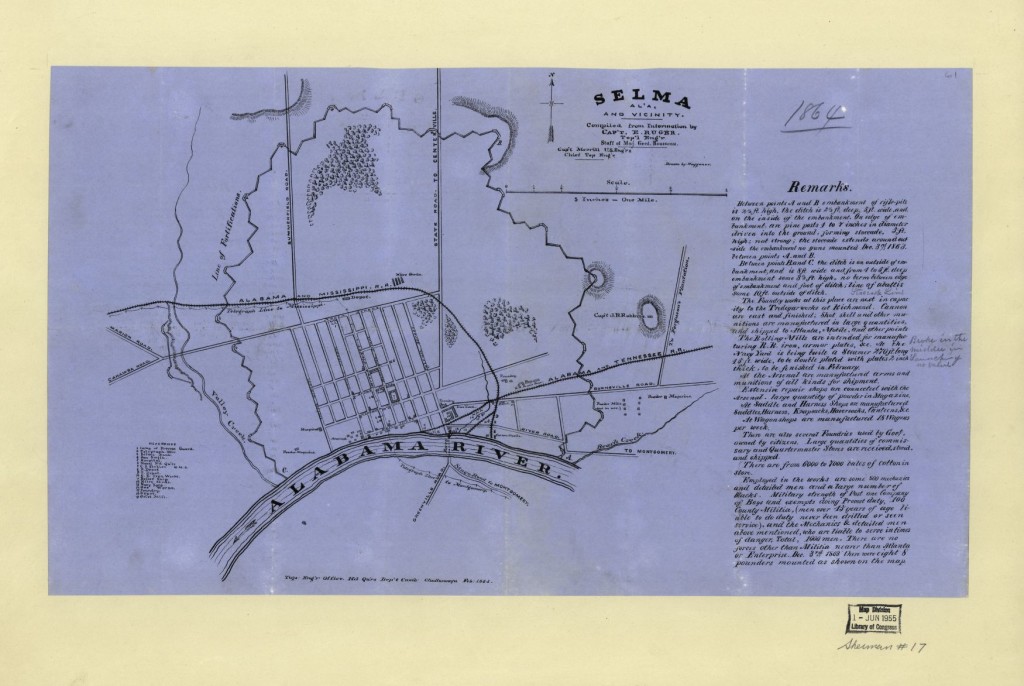

But it also happened that Gen. WILSON, with a large force of cavalry, some seventeen thousand, I believe, in number, commenced a movement from the Tennessee River and a point in the northwest of the State of Alabama, diagonally across the State. He penetrated to the centre, and then radiated from Selma in every direction through one of the most productive regions of the South. That little city of about ten thousand inhabitants — its defences were carried by assault on one of the first Sunday evenings in last April, sun about an hour high. Before another sun rose every house in the city was sacked except two; every woman was robbed of her watch, her ear-rings, her finger-rings, her jewelry of all descriptions, and the whole city given up for the time to the possession of the soldiers. It was a severe discipline to this people. It was thought necessary by the commanding General to reduce and subdue the spirit of rebellion. For one week, the forces under Gen. WILSON occupied that little town, and night after night and day after day one public building after another — first the arsenal, then the foundry, each of which covered about eight or nine acres of ground and was conducted upon a scale commensurate with the demand that military supplies for the war created; railroads depots, machine shops connected with them — everything of that description which had been in any degree subservient to the cause of the rebellion, was laid in ashes. Out of some sixty odd brick stores in the city, forty-nine, I think, were consumed. On the line of march, you were scarcely out of sight of some indication of its terrible consequences. Indeed, after three weeks had elapsed, it was with difficulty you could travel the road from Plantersville to that city, so offensive was the atmosphere in consequence of decaying horses and mules that lay along the roadside. Every description of ruin except the interred dead of the human family met the eye. I witnessed it myself. The fact is that no description can equal the reality. When the Federal forces left that little town — which is built on a bluff on the Alabama River — they crossed on a pontoon bridge and commenced in the night to cross, and their way was lighted by burning warehouses standing on the shore. All this is a part of war — a part of that severe discipline which nations experience, and must expect to share as the fort[u]nes of war vary, when they lay aside reason and appeal to brute force to settle what reason should settle, among Christian people certainly, and especially those who are born beneath the same flag. [Applause.] At the time of these great occurrences, to which I at first alluded, around Richmond, and in connection with Gen. SHERMAN’s army, this devastation was in progress in the State of Alabama. Up to that time, such had been the fortune of war that our State had experienced very little of its baleful effects, except the occupancy of about four counties north of the Tennessee River, and a small skirt of the shore on the Gulf of Mexico. In the South we knew little of the presence of the army, except as prisoners were brought to us to be provided for, and our own sons and brothers were marshalled and carried off to the field. Out of a voting population of ninety thousand. Alabama furnished a hundred and twenty-two thousand men for service in the Confederate army. Thirty-five thousand of these died on the field of battle from wounds or from disease, and a large proportion of those who returned came back broken in health and constitution and disabled by wounds from which they had partially recovered, but which rendered them unfit for active service. The white population of that State was 525,000, according to the census of 1860. At the time Gen. WILSON invaded it, the State was supplying with salt and meal 139,042 women and children and otherwise helpless persons of the white race. Of the black race, there were 440,000, and they, being the property of those who owned them, were supplied with food and everything necessary for their comfortable subsistence physically by their owners. Hence, there never was any necessity in all the States for a public assistance of the blacks. But this eleemosynary assistance to the white race was absolutely necessary. The State had appropriated, at the previous session of the Legislature, seven millions of dollars for the purpose of procuring meal and salt for their relief. Meat was out of the question. Even those comparatively wealthy possessed but little of it, and that little was generally contributed, for the most part, to the army. That was the condition of things in Alabama at the time the Confederacy collapsed. Now, at that time the corn crop of the State was just ready to be plowed and hoed the first time. But the black people being informed of the presence of the Federal forces thought the off-repeated tale of freedom was actually to be verified at last, and concluded they would test the matter, knowing no way of testing it except by quitting work, and seeing whether their masters dared order them back again to the plow-handle and the hoe. That was their only mode — simple, direct, efficacious — of testing the great proposition, “Am I free or not?” [Applause.] The effect on the crop was of course most disastrous; but it tended to satisfy those who made the experiment that there was at least some degree of truth in the idea that they were free. The consequence was that the crop just at the turning point vanished for want of cultivation, besides, a drouth set in of unparalleled severity, and continued all through the crop season; and the result is, that the States, thus depleted of its working force for securing means of subsistence in the commencement of the season to a degree never before known, is now left with about half a crop of corn and small grain. Cotton has not been planted to any extent, because as a matter of course, material for bread must be raised before cotton. This is the actual condition of affairs as given me by the delegates at the recent State convention which assembled in Montgomery in September last. Men of intelligence, candor, fairness in all respects, and whose judgment can be relied on, assured me that it is undoubtedly true that in that State there is not more than one-fifth of a crop of grain for breadstuffs raised. Now, if the same ratio of indigence exists among the black population that exists among the white, it is manifest that there are seven hundred and fifty thousand people in that State who may suffer for food before the month of March comes round. Our resources were completely exhausted, or nearly so, at the commencement of the last Spring. It is therefore manifest that in the State of Alabama these people will suffer unless they are supplied from some source outside the State, for the State is unable to supply them. Such is the condition of the State and its population to-day. When the Treasury of the State was turned over to me in July last, it consisted of about seven hundred dollars in specie, and besides that several millions in Confederate notes, not worth the paper upon which they were printed. Previous to the invasion of Gen. WILSON the State possessed the privilege of purchasing that currency at the rate of one or two cents on a dollar. By the emancipation of the black population of that State one-ha f of the entire taxable value of property is wiped out, and the remaining half, consisting of land, horses, mules, cotton, etc., has been materially reduced — the cotton by burning, the horses and mules by being taken for Confederate or Federal service, and the land, for want of labor to cultivate it, and by means of the destruction of fences, gins, and cotton-presses. You see the actual condition of the State, both as to the body and the individuals of the State separate. These facts are stronger than anything I can say by way of argument — stronger and more comprehensive than any argument I can make in support of them; and, to this audience, I am satisfied no argument is needed to enforce them. The Government of the United States has emancipated the black people, and provided by act of Congress, approved the 3d of March, for the existence and organization of the Freedmen’s Bureau. That bureau, in the State of Alabama, is in charge of Maj.-Gen. SWAYNE, who reached there to take charge of his department at the same time that I reached there, charged, under the commission of the President, with establishing a civil provisional government for the State. In a short time it became apparent to the intelligent and thinking portion of the people, and, as fast as they became acquainted with Gen. SWAYNE, that impression became more and more general, that that bureau, under his skillful administration, being a man of large and comprehensive views, and of strong sense of justice, could be the means and would be the means, if the government did not discontinue it, of aiding those who saw the necessity for aid, until we could realize, from the fruits of another year’s industry, the means of subsistence for these people. As you understand, that bureeu is organized by the Federal Government; it has its confidence; it has all the machinery in operation, ready now to disseminate or distribute material and other aid throughout the State; and it can enlarge its capacity of doing so at pleasure and according to the necessity that exists for it. It has not, however, the means to meet these overwhelming demands upon its resources. While the government assures the bureau that it is willing to do all in its power to sustain it and render it efficient, there is reason to apprehend that much will remain undone for want of necessary means to do it. You see at once from what I have already stated that the means of affording relief, not only to the white people, but to the black people are wanting materially. So far as the blacks are concerned, an entire system of relief is to be inaugurated from the very foundation: and the question is, shall that be temporary in its character, or shall it be of such a description as will insure permanency, and in the future great results to the white. Perhaps it is not necessary to call your attention at this time to it, but I cannot forbear hinting, at least, at the fact that, by means of this great organization, which has now the support of the powerful arm of the government to sustain it, there is an opportunity afforded for inaugurating a sound and efficient system, simple, direct, and to the purpose, which will be as lasting, perhaps, as the demands of the race for whom it is inaugurated. [Loud applause.] If this opportunity is permitted to pass unimproved, it will never present itself again. It is immaterial what may be the color; when it is furnished to them by a heart moved to sympathy on account of their necessities, they, I say, are well prepared to received counsel in connection with it. How much can now be done which will in turn become an instrument to produce other effects, multiplied for others in future years! Aid to this Freedman’s Bureau, therefore, is the great object, I take it, which should be striven for on the part of every one who desires to render efficient aid. It matters not whether he is an individual, or whether he is an individual of a body having for the objects of its organization these great objects in view. I will say, also, in this connection, that it is manifest to every one that only in this way can the people of that section of the South where the war has been raged most furiously and where its destructive effects have been made most apparent — it is in this way only that it can raise a crop another year. Before they can realize the fruit of another year’s industry this class must starve unless assistance is promptly furnished them. And let me say, likewise, ladies and gentlemen, and especially to those of you in this vast city who pursue commercial avocations, scarcely one of whom is not in some way, directly or indirectly, connected with it and affected by it; that nothing is more important to the interests of the United States of America now than to restore business pursuits in all their old relations to each other. A good cotton crop next year will do more to sustain the currency of the Federal Government — to help Mr. MCCULLOCH out of his troubles, if he has any, and perhaps he has — to maintain the supremacy of American manufacturers and commerce on sea and land in the future as they were aforetime — it will do more to thwart the schemes and mischievous clamors of those who whisper to the South: “Free trade and free goods, and down with the Yankee tariff,” than anything else you can devise. [Applause.] It will put a checkmate upon the idea of introducing Egyptian cotton in place of American in the market. I am informed by a distinguished citizen of this State, who is recently from Alexandria, that when he left that port there were fifty-one vessels, steamers, laden with cotton from the Valley of the Nile, which commanded the same price in Liverpool as cotton from the South. Whoever is interested in that trade, desires to have a high export duty placed upon American cotton, because such a duty would be equivalent to a bounty on Egyptian cotton. The same gentleman I refer to — Mr. FIELD, of the Atlantic Telegraph — informed me that English capital, by the thousands and tens of thousands, is being invested in the construation of railroads in India, so that the cotton cultivated and produced in the interior can be taken cheaply and rapidly to the coast, and thus brought to market — an inferior article to the Egyptian, but which goes in to make up the sum necessary. These things, it seems to me, are worth considering. Now, if the cotton-fields of the South, left desolate by the war, without labor, without capital to sustain a laboring force and to procure that which is necessary to carry on the business of raising a new crop; if these fields are permitted to go uncultivated another year. Does it not materially waken a very great interest in the country? I refer to this merely for the purpose of showing how the doctrine of compensation comes in. He who gives forth from his abundance to those who appear to have nothing to give, comes back laden with returns which he little expected to receive. So it will be with us. It is in this that the Union will be restored in the heart more effectually than any bayonet can bind it together. [Loud applause.] It is not by the bayonet that the Union is to be permanently maintained; it is by good offices rather, who live upon the extreme South have an interest in common with those who live upon the extreme North; and I look forward, by the blessing of God, to the time when we who have been lately at bayonet points 6nd swords points shall greet each other, the people of the North coming to the South, bringing their active capital there and uniting it with those who have land and experience necessary to cultivate cotton and other crop, and spending their Winters with their families in the South; to the time, too, when new industry shall have given us new means and resources, enabling us to go to the North and spend our Summers upon your lake shores and your cool rivers and mountains. That will be the sort of union that will secure harmony and peace. With the widowed wife, surrounded by her fatherless children, let us sympathize, regretting the strife which has produced her bereavement; and if our lips speak words of mutual kindness away in the distant home by the pine forests, along the distant streams, a response will be awakened which nothing but that tribute of kindness could have called forth. It is indeed by such means that we shall at last hear one universal song of gratitude going up over the land; because the giver will be happy in having bestowed where his bounty was needed, where it brought hope once more to the heart that was ready to despair; and the receiver will be happy, because it opens to him a future of prosperiy. But I will not enlarge on this theme. I leave it for your consideration. When you shall have heard from those who have participated in scenes of battle, and from these who have the power of painting with words as the artist does with the brush or pencil, I know you will respond. I thank you for this evidence of your interest, which this large assembly indicates, in the fate of a portion of our common country. I shall bear back the evidence with me when I refuse to those among whom I live; and I shall tell them what I have found to be almost universally true in every individual instance since I have been in the North, that there is a kindly feeling which we had no idea existed among the great mass of the people. [Applause.] And let me say, my friends, that if you see in the newspapers of the South unkind things, take no account of them. Newspapers do not always speak the real sentiments of the people. If you find there is occasionally an outbreak, bear in mind the terrible sufferings which have been undergone by our people. Make allowances for that. Do not be discouraged if you do not find that prompt and effectual change which you desire. Everything good and great in this world, both in nature and in man, is the result of time and effort. [Applause.] It is only the weak, the useless, that springs up in a day and perishes as quickly. All great undertakings must be patiently labored for and discouragements patiently borne, when everytning does not work as we desire. [Applause.] Fncourage that feeling and that hope. Let us persevere in the great effort of pacifying, restoring and uniting the hearts of our people, that thereby the strength and the glory of our nation may be increased; that, if the time shall ever come when, in the Providence of God, we are called upon to take up arms in a common cause, we may stand shoulder to shoulder, in the conflict. After the soldiers of the North and of the South have met each other on the field in deadly strife, I know no one will feel less confidence than heretofore in the success of a mutual cause when they again stand under the same flag, rallying round it, and bearing it forward. [Applause.] If, at such a time, my friends, we fail to do our part as men, then call us cowards, then say we are whipped; but don’t say it till then. [Loud applause.]

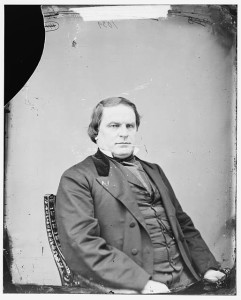

Lewis Eliphalet Parsons was born in the Southern Tier of New York State. He moved to Alabama when he was about 23 years old. He practiced law and politics but also fought for the Confederacy during Wilson’s Raid: “Parsons fought as a Confederate lieutenant at the brief Battle of Munford near Talladega in April, 1865.”

For a man bent on making treason odious and displacing the South’s traditional leadership, Andrew Johnson displayed remarkable forbearance in choosing provisional governors to launch the reconstruction process. [Except for Texas and North Carolina] Johnson passed over unconditional loyalists to select men acceptable to a broader segment of white public opinion. … In Alabama, Johnson ignored the upcountry Unionist opposition and selected Lewis E. Parsons, a former Whig Congressman who served as a “peace party” member of the wartime Alabama legislature and enjoyed close ties to the state’s mercantile and railroad interests.[1]

LOC: Lewis E. Parsons, General Wilson, map

- [1]Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: HarperPerennial, 2014. Updated Edition. Print. page 187.↩