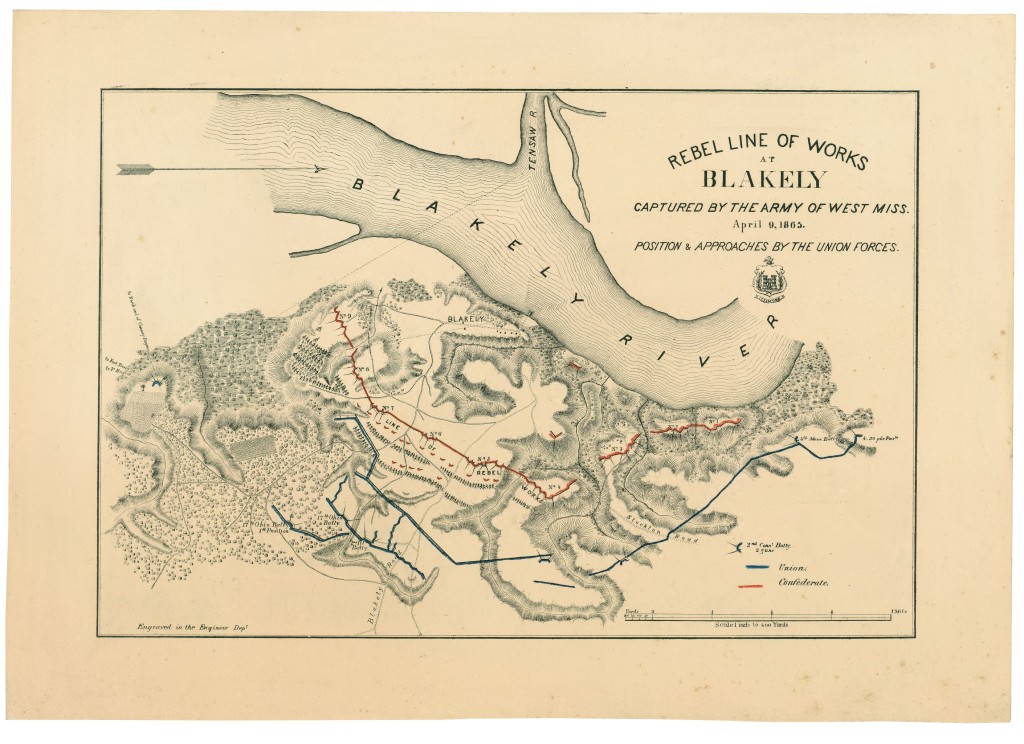

at Fort Blakely – “Probably the last charge of this war, it was as gallant as any on record.” (Harper’s Weekly 5-27-1865

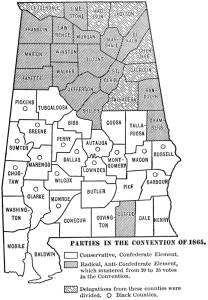

It’s going on six months since federal troops won the Battle of Fort Blakely on April 9, 1865 and a few days later occupied Mobile, Alabama. It is written that “The siege and capture of Fort Blakely was basically the last combined-force battle of the war.” Alabama was also the first home of the Confederate capital. 150 years ago this week delegates to a state convention passed an ordinance outlawing slavery in the state.

In Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama (1905; well-referenced) Walter L. Fleming discussed the convention and recapped the debate regarding the abolition of slavery:

In the debate in regard to the abolition of slavery, Mr. Coleman of Choctaw desired to know by what authority the people of Alabama had been deprived of their constitutional right to property in slaves. He urged the convention not to pass an ordinance to abolish slavery, but to leave the President’s proclamations and the acts of Congress to be tested by the Supreme Court; that there was no such thing as secession; a state could not be guilty of treason, and Alabama had committed no crime; individuals had done so; others were loyal and were entitled to their rights. Not only those who had always been loyal but also those who had taken the amnesty oath were entitled to their property; those pardoned by the President were entitled to the same rights, and Congress had no authority to seize property except during the lifetime of the criminal. The Federal government had no right to nullify the Constitution. The abolition of slavery should be accepted as an act of war, not as the free and voluntary act of the people of Alabama which latter course would prevent the “loyalists” of Alabama, from receiving compensation for slaves. He denied that slavery was non-existent; Lincoln’s proclamation did not destroy slavery; it was a question for the Supreme Court to decide, and to admit that Lincoln’s proclamation destroyed slavery was to admit the power of the President and Congress to nullify every law of the state. For all these reasons it was inexpedient for the convention to declare the abolition of slavery.

Judge Foster of Calhoun answered that the war had settled the question of slavery and secession; that the question of slavery was beyond the power of the courts to decide, and, besides, a decision of the Supreme Court would not be respected. The question had to be decided by war, and having been so decided, there was no appeal from the decision. The institution of slavery had been destroyed by secession. The question was not open for discussion. Slavery, he said, does not exist, is utterly and forever destroyed,—by whom, when, where, is no matter. The power of arms is greater than all courts. Citizens should begin to make contracts with their former slaves. Should the Supreme Court declare the proclamations of the Presidents and the acts of Congress unconstitutional, slavery would not be restored. Whether destroyed legally or illegally, it was destroyed, and the people had better accept the situation and restore Federal relations.

Mr. White of Talladega proposed to abide by the proclamations of the President and the acts of Congress until the Supreme Court should decide the question of slavery. White said that he had opposed secession as long as he could; that the states were not out of the Union, but had all their rights as formerly. Mr. Lane of Butler wanted an ordinance to the effect that since the institution of slavery had been destroyed in the state of Alabama by act of the Federal government, therefore slavery no longer exists. This was lost by a vote of 66 to 17. On September 22, 1865, an ordinance was adopted by a vote of 89 to 3 which declared that the institution of slavery having been destroyed, neither slavery nor involuntary servitude should thereafter exist in the state, except as a punishment for crime. All provisions in the constitution regarding slavery were struck out, and it was made the duty of the next legislature to pass laws to protect the freedmen in the full employment of all their rights of person and property and to guard them and the state against any evils that might arise from their sudden emancipation. Mr. Taliafero Towles of Chambers, a “loyalist,” proposed an ordinance to make all “free negroes” who were not inhabitants of the state before 1861 leave the state. Mr. Langdon of Mobile regretted this proposition, and thought it would do harm. Mr. Towles explained that he lived near the Georgia line and that he was much annoyed by the negroes who came into Alabama from Georgia. Mr. Patton of Lauderdale opposed such a policy. It was unwise, he said; let people go where they pleased; he would invite people from all parts of the Union to Alabama. Mr. Mudd of Jefferson thought that such a measure would be extremely unwise. Mr. Hunter of Dallas said that it was very unwise, that it would do no good, and at such a time would be harmful. Passions must be allayed. Towles withdrew the resolution.

“Historic Blakeley State Park, scene of the last major battle of the Civil War, Spanish Fort, Alabama ” (Library of Congress)