150 years ago this week a Northern newspaper reprinted a report it found in a Petersburg, Virginia newspaper. A city that began the year under siege was trying to adjust to the huge change in the economic-social system caused by losing the war and the abolition of slavery. There was a large influx of former slaves into Virginia’s towns and cities, which would be an especial cause of concern with the inevitable return of winter. The former slaves did not seem to be sticking to one job for long. Black churches and schools seemed to be training former slaves in such a way as to “create irritation and sow discord between the two races.” Slavery was a mutually beneficial system, but postbellum there would be more obvious lines of demarcation between the races leading eventually to “the great separation.” The schools seemed to be spending more time instigating blacks to harm whites than in teaching reading and writing. The paper concluded by saying that the time was right to colonize Africa with the freed slaves.

From The New-York Times August 6, 1865:

SOME OF WAR’S CHANGES.; Effects of the Abolition of Slavery from a Southern Point of View. The Old Song of the Benefits of Slavery and the Hardships of Freedom.

The following article from the Petersburgh Daily Index shows how hard it is for the South to give up its old idea in regard to slavery, and the determination of a certain class to make freedom a curse to both races:

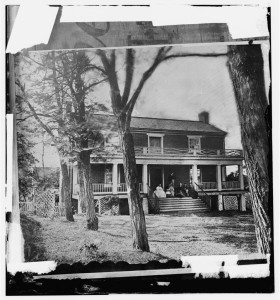

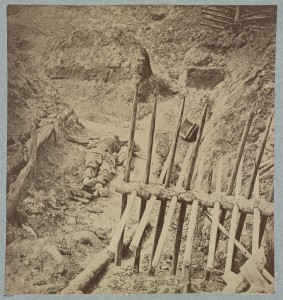

“Dead Confederate soldier in trenches of Fort Mahone in front of Petersburg, Va., April 3, 1865 ” (Library of Congress)

“By the operation of war — a more potent agency than laws or ordinances — slavery ceased to exist among us four months ago this day. The time has, of course, been too short, and our experience too restricted, to warrant any generalization of the facts and results of this radical revolution in an institution whose age is numbered by centuries, but since the reports of many observers will be required to enable the world to make a right estimate of the results of this forcible destruction of the labor system, and by consequence of the social system of the South, we offer our contribution to the common stock. We have to speak only of what falls under our own eye, and therefore only of the effects in a city.

The first, and perhaps the most conspicuous result, was the immediate and very considerable increase of the numbers of the negroes among us.

Animated by curiosity, by a wish for change, by the hope of more abundant and regular contributions of food from the Federal hand, by the natural desire for the association, sympathy and converse of as large a number of their fellows as possible, by the larger opportunities of making money through the greater diversity of pursuits, probably in some instances by the greater profits of vice, as well as the greater impunity which the opportunities of city life insure, by the distaste for the regular labor of the farm, by the love of a holiday — by all these and perhaps other motives, there arose, immediately after the surrender of Gen. LEE, a steady influx of negroes into the towns and cities of the State. As soon as the attention of the military authorities in immediate command, was called to the certain evil that threatened both town and country, as a result of this, they adopted stringent rules to prevent the further spread of the evil, and compelled hundreds who were living exclusively on the bounty of the government, to return to their homes, where they would be useful, and could be fed.

Still the remedy was necessarily partial, and the result of the census now being taken will show that the colored population of Petersburgh has doubled in four months. During the Summer, when food is cheap, when no fire is needed, save for cooking, when little clothing is required and the cheapest material suffices, when it is easy to supply the limited needs of the body by the few cents which can be gained by retailing lemonade, hawking fruit about the streets, blacking boots, vending newspapers, holding officers’ horses, acting as porters at the railway stations, huckstering, fishing and other light employments of the long Summer day, and when, finally, the presence of the military ensures labor to many and food to many more who will one day have to provide for themselves — during the Summer, we say, this great increase of population is a matter which concerns us no otherwise than as it affects public order; but in the Winter, such an increase of a population that will not, because they cannot, produce as much as they consume, will be a serious, indeed an intolerable tax upon the charity, public and private, of our people.

In the next place, it is discouraging to observe — and the observation is very general — the unfaithfulness of the hired servants to their obligations. In the majority of cases which have fallen under our observation, the domestic servants cannot be relied on to stay in any one employment a week at a time. This is not due to the inadequacy of wages, because the labor performed is better paid than that of any servant in the country, North or South. Nor is it due to the impositions of employers, for as our readers, especially our colored ones, if we are so fortunate to have any, very well know, speedy, certain and complete redress is afforded by the Provost-Marshal to any negro who has cause of complaint. Neither is it attributable to a corresponding infidelity of the employer to perform his part of the contract, for the enforcement against him is always easy. It is due to (what we hope for the mutual interest of both races, it may not be found to be) an incurable aversion of the negro to regular, continuous, persevering labor. If further experience should prove this to be a result of slavery, of the want of that stimulus which a direct and disposable return for labor occasions, then the evil will soon wear off, as the necessities and interests of the negro become clearer to himself. At present the trouble is a most serious and annoying one. Hardly a housekeeper can be certain on Sunday night that his Monday breakfast will be cooked for him.

A third result is the violence and insolence which seems suddenly to have sprung up, especially among the young. This was, of course, to be expected, and we are agreeably disappointed in finding comparatively so little of it. The majority of the enfranchised slaves behave with a degree of good manners and respect which, considering the influences to which they are subjected in their churches and schools, is very creditable to them.

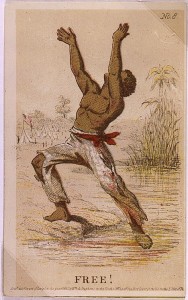

school song (Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, America Singing: Nineteenth-Century Song Sheets.)

From the time of the advent of the Federal troops, their churches have been open almost, if not quite, daily, and some very silly and other very wicked people have been availing themselves of the opportunities that afforded to instill into their minds very loose notions of the supremacy of law, and the sacredness the right of property. In addition, some schools are open whose teachers find it easier to train the voices than the brains of their charges; and thoughts, who cannot compass the alphabet, know every inflection of “Hang Jeff. Davis on a Sour Apple Tree,” “Down with the Traitors and up with the Flag,” “John Brown’s Body,” and the other national melodies which the war has substituted for the “Star-Spangled Banner” and “Yankee Doodle.”

The result, and of course the design of all this, as well as of the training of the urchins in the manual of arms under officers of their own color, armed with United States sabres, is to create irritation and sow discord between the two races, and we are less surprised that the attempt should have been made, than that it should have met with such trifling success.

Many, indeed most of the older and more respectable of the colored population, are as orderly and polite as ever, and some, who at first wore their new honors somewhat obtrusively, have, under the wholesome counsel and restraints of the military authority, had their eyes open to the imposing fact that Fourth of July is not food, nor “Hail Columbia” raiment.

Another result, and one that will inevitably and forever attend the substitution of freedom for slavery, where different races are the subjects, is the deepening of the lines of demarcation, social and industrial, between the whites and the blacks. The jealousy of race is the most difficult of all jealousies to eradicate, because it is an instinct. Hitherto in the South that jealousy has been softened by the mutual interchange of useful offices, and by the union of families for generations. In thousands of cases in the South, the nurse, or “mammy” of the child, was the granddaughter of the nurse of that child’s grandfather, and the servants who waited in the house or tilled the farm, were the descendants of those who performed the like offices for the ancestors of their masters for generations. The result was an attachment which long habits of association in the practical relations of service and protection, never fails to originate, even when a brute renders the one and receives the other. Every one who knows anything of slavery in Virginia, knows the depth and universality of these attachments, how the family servant was an object of family pride, how the young were defended for their parent’s sakes, and the old cherished for the services they had rendered, and the fondness with which they remembered those who were “loved and lost” — how frequently, in a word, the question of economy, of what was best for the balance sheet was postponed to the ties of traditional and inherited affection.

Thus it was that despite the most persistent efforts to excite insurrection by the evil disposed during the secession, the unparalleled spectacle was witnessed of a four years war for the enfranchisement of the slave, fought out to success without a single outbreak among the slaves themselves, in any single quarter or corner of the whole South — an imperishable monument of the humanity of Southern slavery, and a triumphant and unanswerable refutation of the abuse that for forty years has been heaped on Southern masters.

This mollifying influence is now gone, and the races are left to the operation of the hard laws of selfishness and interest, and the results are as might have been anticipated.

Formerly a white drayman or cartman or back-driver was a sight unknown to our streets, now they share these employments with the blacks, and eventually will monopolize them, except in cases — and there are many among us — where, under the brutalizing effects of slavery, colored men heretofore carrying on these employments have won enviable characters for trustworthiness, politeness and honesty.

Formerly, most, if not all, of our bars were tended by colored men, though owned by whites; now, the cobblers and juleps are mixed, as well as the rent paid, and the stock kept up by white men in many instances. Formerly, the restaurants of Petersburgh were almost exclusively in the hands of the colored people; now, we believe, there is but one establishment of the sort in the city. Formerly, we had only colored barbers; now, the native whites seek, generally, barbers of their own color, and eventually, they will do so exclusively. Formerly, both colors purchased their groceries of white men; now, there are at least two family groceries of respectable size, managed and sustained exclusively by the blacks. And this will infallibly go on until the great separation, which God has for some wise purpose indicated with such signal and ineffaceable distinctness, will be recognized and maintained in all the walks of life, as rigidly as it is everywhere observed in social intercourse, and the familiarity of acquaintanceship and friendship.

We have only space this morning to add one more of the effects of freedom — the extension of the rudiments of education. The little we know of the system by which this end is sought here, does not impress us favorably as to the final result, for if we are rightly informed, the teachers are, in some cases, much more solicitous to persuade their pupils that their late masters are their natural enemies, whom it would be an acceptable service to God to rob and injure, much after the fashion that the subjects of Pharoah were treated by their freedmen, than to lead them through the mysteries of the spelling book. Nevertheless, we unhesitatingly bid God-speed to all who offer them a true education — an education of conscience and heart, as well as mind. No greater calamity could befall this State than the cur[s]e of a population of four hundred thousand beings growing up, living, acting and dying in ignorance, and with no restrain but their own wills.

Perhaps here will be found the realization of that vision which, for generations, reconciled many to slavery, who otherwise esteemed it a great evil — the regeneration and civilization and christianizing of Africa.

Sixty-five years ago this matter engaged the serious attention of the Virginia Legislature. Mr. JEFFERSON extenuated slavery on the ground that one day the slaves might “carry back to the country of their origin the seeds of civilization.” Fifty years ago, the General Assembly, with but ten dissenting voices in both houses, urged the plan of colonization on the attention of Congress, for “persons of color now free, and such as may be hereafter emancipated.” The first names in Virginia history have been the first names in the history of colonization — JEFFERSON, MONROE, JOHN RANDOLPH, MARSHALL, MADISON, MERCER, Bishop MEADE, TYLER. The dream of all these men was to redeem Africa from degradation and wretchedness, through the Africans. They seem never to have been discouraged by the thought that they were trying to dissolve a polar iceberg with a burning glass. Here, at last, is a means adequate to the task, and the performance of that task is at once the regeneration of Africa, and the redemption of America: and here, at last, is the prospect of fruition for the prophecy of a distinguished son of the Commonwealth: “Africa gave to Virginia a savage and a slave; Virginia gives back to Africa a citizen and a Christian.”

Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves, but even he considered sending them back to Africa.

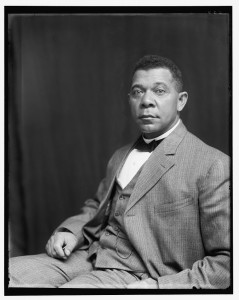

In the blink of an eye, or when General Lee signed the surrender agreement at Appomattox Courthouse, the white South went from trying to defend the Confederate States of America and its way of life to a whole new world. Former slaves also faced a whole new world. In 1901’s Up From Slavery: An Autobiography (at the end of Chapter 1) Booker T. Washington looked back to 1865 when, as a child of probably eight or nine, he and the rest of the slaves on his master’s plantation in Franklin County, Virginia were proclaimed free:

Finally the war closed, and the day of freedom came. It was a momentous and eventful day to all upon our plantation. We had been expecting it. Freedom was in the air, and had been for months. Deserting soldiers returning to their homes were to be seen every day. Others who had been discharged, or whose regiments had been paroled, were constantly passing near our place. The “grape-vine telegraph” was kept busy night and day. The news and mutterings of great events were swiftly carried from one plantation to another. In the fear of “Yankee” invasions, the silverware and other valuables were taken from the “big house,” buried in the woods, and guarded by trusted slaves. Woe be to any one who would have attempted to disturb the buried treasure. The slaves would give the Yankee soldiers food, drink, clothing—anything but that which had been specifically intrusted to their care and honour. As the great day drew nearer, there was more singing in the slave quarters than usual. It was bolder, had more ring, and lasted later into the night. Most of the verses of the plantation songs had some reference to freedom. True, they had sung those same verses before, but they had been careful to explain that the “freedom” in these songs referred to the next world, and had no connection with life in this world. Now they gradually threw off the mask, and were not afraid to let it be known that the “freedom” in their songs meant freedom of the body in this world. The night before the eventful day, word was sent to the slave quarters to the effect that something unusual was going to take place at the “big house” the next morning. There was little, if any, sleep that night. All as excitement and expectancy. Early the next morning word was sent to all the slaves, old and young, to gather at the house. In company with my mother, brother, and sister, and a large number of other slaves, I went to the master’s house. All of our master’s family were either standing or seated on the veranda of the house, where they could see what was to take place and hear what was said. There was a feeling of deep interest, or perhaps sadness, on their faces, but not bitterness. As I now recall the impression they made upon me, they did not at the moment seem to be sad because of the loss of property, but rather because of parting with those whom they had reared and who were in many ways very close to them. The most distinct thing that I now recall in connection with the scene was that some man who seemed to be a stranger (a United States officer, I presume) made a little speech and then read a rather long paper—the Emancipation Proclamation, I think. After the reading we were told that we were all free, and could go when and where we pleased. My mother, who was standing by my side, leaned over and kissed her children, while tears of joy ran down her cheeks. She explained to us what it all meant, that this was the day for which she had been so long praying, but fearing that she would never live to see.

For some minutes there was great rejoicing, and thanksgiving, and wild scenes of ecstasy. But there was no feeling of bitterness. In fact, there was pity among the slaves for our former owners. The wild rejoicing on the part of the emancipated coloured people lasted but for a brief period, for I noticed that by the time they returned to their cabins there was a change in their feelings. The great responsibility of being free, of having charge of themselves, of having to think and plan for themselves and their children, seemed to take possession of them. It was very much like suddenly turning a youth of ten or twelve years out into the world to provide for himself. In a few hours the great questions with which the Anglo-Saxon race had been grappling for centuries had been thrown upon these people to be solved. These were the questions of a home, a living, the rearing of children, education, citizenship, and the establishment and support of churches. Was it any wonder that within a few hours the wild rejoicing ceased and a feeling of deep gloom seemed to pervade the slave quarters? To some it seemed that, now that they were in actual possession of it, freedom was a more serious thing than they had expected to find it. Some of the slaves were seventy or eighty years old; their best days were gone. They had no strength with which to earn a living in a strange place and among strange people, even if they had been sure where to find a new place of abode. To this class the problem seemed especially hard. Besides, deep down in their hearts there was a strange and peculiar attachment to “old Marster” and “old Missus,” and to their children, which they found it hard to think of breaking off. With these they had spent in some cases nearly a half-century, and it was no light thing to think of parting. Gradually, one by one, stealthily at first, the older slaves began to wander from the slave quarters back to the “big house” to have a whispered conversation with their former owners as to the future.

This instant freedom is hard for me to imagine. I had over twenty years to gradually learn the skills necessary to become relatively self-reliant.

The following photograph of Richmond between April and June 1865 also seems to give some idea of the postbellum disruption:

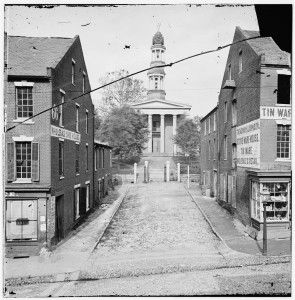

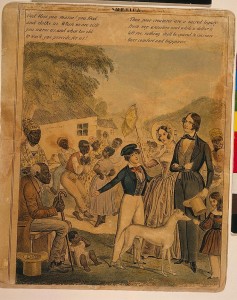

You can read about the image of the contented plantation at the Library of Congress, which also provides more information about the Petersburg Courthouse: “During the 1864-1865 siege of Petersburg, Union troops used the tower for a sighting mark and both Confederates and Federals relied upon the clock in the tower as a timepiece.”