The June 4, 1865 issue of The New-York Times headlined the huge national debt that Secretary of the Treasury Hugh McCulloch reported. The following article (which we know was published sometime in May) argued that the burden of a nation’s debt is relative to its productive capacity. The United States was continuing to grow and was using technology to become increasingly productive. Consequently, its tax base was growing and large enough to pay the debt.

From The Atlantic Monthly, VOL. XV.—JUNE, 1865.—NO. XCII.:

MODERN IMPROVEMENTS AND OUR NATIONAL DEBT.

At the commencement of the Rebellion it was the general opinion of statesmen and financiers in other countries, and the opinion of many among ourselves, that our resources were inadequate to a long continuance of the war, and that it must soon terminate under pecuniary exhaustion, if from no other cause. Our experience has shown that this view was fallacious. After having sustained for several years the largest army known to modern times, our available resources seem to be unimpaired. The country is, indeed, largely in debt; but its powers of production are so great that it can undoubtedly meet all future demands as easily as it has met those of the past.

The ability or inability of a nation engaged in war to sustain heavy public expenses is to be measured not so much by its nominal debt as by the relation which the sum of its production bears to that of its necessary consumption. A nation heavily in debt may continue to make large public expenditures and still prosper and increase in wealth, if its powers of production are correspondingly large also. It is a fact of the most encouraging kind, that the power of production exhibited by the United States far exceeds, in proportion to their population, that of any other nation heretofore involved in a long and costly war. The case which most nearly approaches ours, in this regard, is that of England, during her war with Napoleon, from 1803 to 1815. But since the termination of that long contest, the progress of discovery, improvements in the machinery and in the processes of manufacture, more effective implements of agriculture, the general introduction of railways,[H] and other time- and labor-saving agencies, together with the constantly increasing influence of the applied sciences, have so augmented the productive power of humanity, that the experience of the most advanced nations fifty years ago furnishes no adequate criterion of what the United States can do now.

It is not easy to determine the precise ratio in which production has been increased by these instrumentalities. It is unquestionably very large,—not less, probably, than threefold. That is to say, a given population, including all ages and conditions, can produce the articles necessary for its subsistence, such as food, clothing, and shelter, to an extent three times as great, with these agencies, as it could produce without them. Hence it appears, that, if the people of the loyal States could return to the standard of living that prevailed fifty years ago, the amount of their production would be sufficient to subsist not only themselves, but twice as many more in addition. To accomplish this, they would have, indeed, to devote themselves more to the production of articles of prime necessity and less to those of mere ornament and luxury. That they have the productive energy necessary to such a result there can be no doubt.

This encouraging view of our condition is fully sustained by official statements, which show that the industrial products of the country increase in a greater ratio than the population. In 1850 the aggregate value of the products of agriculture, mining, manufactures, and the mechanic arts, in the United States, was $2,345,000.000. In 1860 the aggregate was $3,756,000,000. This is an increase in ten years of sixty per cent, whereas the increase of population during that decade was only thirty-five and a half per cent. Thus we see that during the ten years ending with 1860—the date of the last census—the products of the industry of the country increased almost twice as fast as the population increased. If to this we add the remarkable fact that the value of taxable property increased during the same period a hundred and twenty-six per cent, we have striking proof of the existence of a vast and rapidly increasing productive power,—a power largely due to the influence of those improvements which have been alluded to.

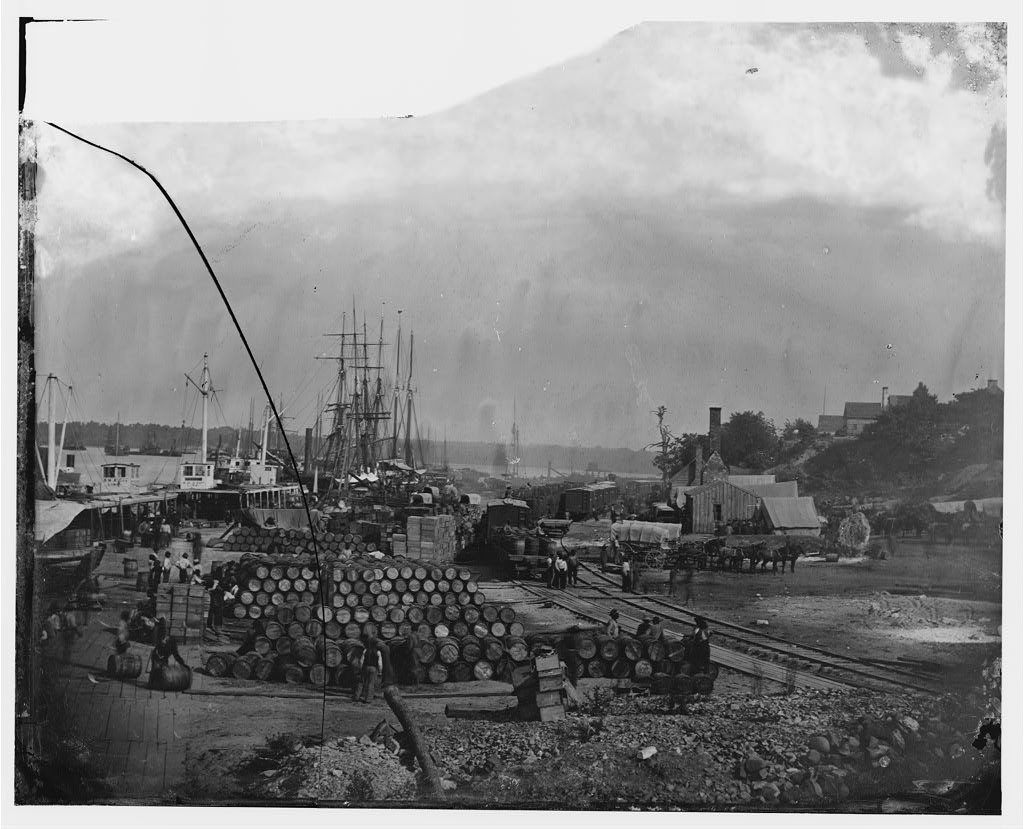

One obvious effect of war is to transfer a portion of labor from the sphere of effective production to that of extraordinary consumption. To what extent the relations of production and consumption among us have been changed during the present contest it is impossible to state. That consumption has been largely increased by our military operations is apparent to all. It is equally apparent that production also has been augmented, though not, perhaps, to the same extent. The extraordinary demand for various commodities for war purposes has brought all the producing agencies of the country into a high state of activity and efficiency, giving to the loyal States a larger aggregate production than they had before the war. Of mining and manufactures this is unquestionably true. As regards the products of the soil, the Commissioner of Agriculture, in his Report for 1863, says,—”Although the year just closed has been a year of war on the part of the Republic, over a wider field and on a grander scale than any recorded in history, yet, strange as it may appear, the great interests of agriculture have not materially suffered in the loyal States…. Notwithstanding there have been over a million of men employed in the army and navy, withdrawn chiefly from the producing classes, and liberally fed, clothed, and paid by the Government, yet the yield of most of the great staples of agriculture for 1863 exceeds that of 1862…. This wonderful fact of history—a young republic carrying on a gigantic war on its own territory and coasts, and at the same time not only feeding itself and foreign nations, but furnishing vast quantities of raw materials for commerce and manufactures—proves that we are essentially an agricultural people; that three years of war have not as yet seriously disturbed, but rather increased, industrial pursuits; and that the withdrawal of agricultural labor, and the loss of life by disease and battle, have been more than compensated by machinery and maturing growth at home, and by the increased influx of immigration from abroad.”

In illustration of the character of those agencies to which we owe the remarkable and gratifying results thus portrayed by the Commissioner, I give the following official statement in regard to two of the more prominent modern implements of agriculture. Mr. Kennedy, in his Census Report for 1860, informs us “that a threshing-machine in Ohio, worked by three men, with some assistance from the farm hands, did the work of seventy flails, and that thirty steam-threshers only were required to prepare for market the wheat crop of two counties in Ohio, which would have required the labor of forty thousand men.” As it took probably less than two hundred men to work the machines, the immense saving in human labor becomes instantly apparent.

Again, in his last Patent-Office Report, Mr. Holloway states “that from reliable returns in his possession it is shown that forty thousand reapers were manufactured and sold in 1863, and that it is estimated by the manufacturers that over ninety thousand will be required to meet the demand for 1864”; and these machines, he says, will save the labor of four hundred and fifty thousand men.

If the aggregate produce of the loyal States, notwithstanding the large amount of labor that has been withdrawn from production by the demands of the war, is actually greater than ever before, and if, as we have already shown, the sum of that produce is three times as great as the people of those States, using proper economy, would necessarily consume, surely no one should feel any anxiety in regard to the ability of the United States to meet all their pecuniary obligations. …

We need but a resolute and united purpose to sustain with comparative ease our national burdens, whatever may be their extent. Those who doubt this under-estimate not only the magnitude of our national resources, but the powerful aid which modern improvements lend to their development.

FOOTNOTES:

[H] Some estimate of the influence of railways alone may be formed by reference to the following statement, which occurs in an address of Robert Stephenson before the Institution of Civil Engineers, in 1856:—

“The result, then, is, that, upon the existing traffic of the United Kingdom of Great Britain, railways are affecting a direct saving to the people of not less than forty million pounds per annum; and that sum exceeds by about fifty per cent the entire interest of our national debt. It may be said, therefore, that the railway system neutralizes to the people the bad effects of the debt with which the state is incumbered. It places us in as good position as if the debt did not exist.”