150 years ago this week the Utica Morning Herald & Daily Gazette (at the Library of Congress) devoted its front page to a reprint of an article that assessed Abraham Lincoln’s historical significance. The president did not seem up to the huge task of saving the Union upon taking office, but he was helped by the synergy that developed between him and the American people (Northern), who “showed strength and virtues which they were hardly conscious of possessing.” Mr. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was decisive for the successful conclusion of the war and to give him a place in universal history. Most of the piece recounted the history of slavery in America. Here’s mostly the conclusion from the June 1865 issue of The Atlantic Monthly:

THE PLACE OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN IN HISTORY.

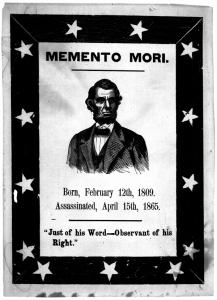

The funeral procession of the late President of the United States has passed through the land from Washington to his final resting-place in the heart of the Prairies. Along the line of more than fifteen hundred miles his remains were borne, as it were, through continued lines of the people; and the number of mourners and the sincerity and unanimity of grief were such as never before attended the obsequies of a human being; so that the terrible catastrophe of his end hardly struck more awe than the majestic sorrow of the people. The thought of the individual was effaced; and men’s minds were drawn to the station which he filled, to his public career, to the principles he represented, to his martyrdom. There was at first impatience at the escape of his murderer, mixed with contempt for the wretch who was guilty of the crime; and there was relief in the consideration, that one whose personal insignificance was in such a contrast with the greatness of his crime had met with a sudden and ignoble death. No one stopped to remark on the personal qualities of Abraham Lincoln, except to wonder that his gentleness of nature had not saved him from the designs of assassins. It was thought then, and the event is still so recent it is thought now, that the analysis and graphic portraiture of his personal character and habits should be deferred to less excited times; as yet the attempt would wear the aspect of cruel indifference or levity, inconsistent with the sanctity of the occasion. Men ask one another only, Why has the President been struck down, and why do the people mourn? We think we pay the best tribute to his memory and the most fitting respect to his name, if we ask after the relation in which he stands to the history of his country and his fellow-man.

Before the end of 1865, it will have been two hundred and forty-six years since the first negro slaves were landed in Virginia from a Dutch trading-vessel,…

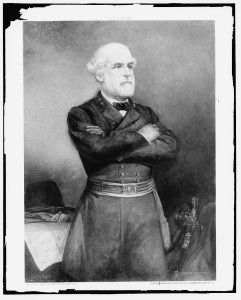

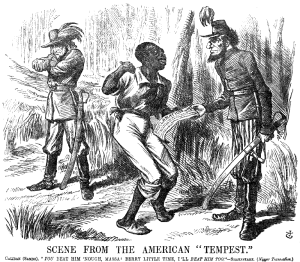

The position of Abraham Lincoln, on the day of his inauguration, was apparently one of helpless debility. A bark canoe in a tempest on mid-ocean seemed hardly less safe. The vital tradition of the country on Slavery no longer had its adequate expression in either of the two great political parties, and the Supreme Court had uprooted the old landmarks and guides. The men who had chosen him President did not constitute a consolidated party, and did not profess to represent either of the historic parties which had been engaged in the struggles of three quarters of a century. They were a heterogeneous body of men, of the most various political attachments in former years, and on many questions of economy of the most discordant opinions. Scarcely knowing each other, they did not form a numerical majority of the whole country, were in a minority in each branch of Congress except from the wilful absence of members, and they could not be sure of their own continuance as an organized body. They did not know their own position, and were startled by the consequences of their success. The new President himself was, according to his own description, a man of defective education, a lawyer by profession, knowing nothing of administration beyond having been master of a very small post-office, knowing nothing of war but as a captain of volunteers in a raid against an Indian chief, repeatedly a member of the Illinois Legislature, once a member of Congress. He spoke with ease and clearness, but not with eloquence. He wrote concisely and to the point, but was unskilled in the use of the pen. He had no accurate knowledge of the public defences of the country, no exact conception of its foreign relations, no comprehensive perception of his duties. The qualities of his nature were not suited to hardy action. His temper was soft and gentle and yielding; reluctant to refuse anything that presented itself to him as an act of kindness; loving to please and willing to confide; not trained to confine acts of good-will within the stern limits of duty. He was of the temperament called melancholic, scarcely concealed by an exterior of lightness of humor,—having a deep and fixed seriousness, jesting lips, and wanness of heart. And this man was summoned to stand up directly against a power with which Henry Clay had never directly grappled, before which Webster at last had quailed, which no President had offended and yet successfully administered the Government, to which each great political party had made concessions, to which in various measures of compromise the country had repeatedly capitulated, and with which he must now venture a struggle for the life or death of the nation.The credit of the country had not fully recovered from the shock it had treacherously received in the former administration. A part of the navy-yards were intrusted to incompetent agents or enemies. The social spirit of the city of Washington was against him, and spies and enemies abounded in the circles of fashion. Every executive department swarmed with men of treasonable inclinations, so that it was uncertain where to rest for support. The army officers had been trained in unsound political principles. The chief of staff of the highest of the general officers, wearing the mask of loyalty, was a traitor at heart. The country was ungenerous towards the negro, who in truth was not in the least to blame,—was impatient that such a strife should have grown out of his condition, and wished that he were far away. On the side of prompt decision the advantage was with the Rebels; the President sought how to avoid war without compromising his duty; and the Rebels, who knew their own purpose, won incalculable advantages by the start which they thus gained. The country stood aghast, and would not believe in the full extent of the conspiracy to shatter it in pieces; men were uncertain if there would be a great uprising of the people. The President and his cabinet were in the midst of an enemy’s country and in personal danger, and at one time their connections with the North and West were cut off; and that very moment was chosen by the trusted chief of staff of the Lieutenant-General to go over to the enemy.

Every one remembers how this state of suspense was terminated by the uprising of a people who now showed strength and virtues which they were hardly conscious of possessing.

In some respects Abraham Lincoln was peculiarly fitted for his task, in connection with the movement of his countrymen. He was of the Northwest; and this time it was the Mississippi River, the needed outlet for the wealth of the Northwest, that did its part in asserting the necessity of Union. He was one of the mass of the people; he represented them, because he was of them; and the mass of the people, the class that lives and thrives by self-imposed labor, felt that the work which was to be done was a work of their own: the assertion of equality against the pride of oligarchy; of free labor against the lordship over slaves; of the great industrial people against all the expiring aristocracies of which any remnants had tided down from the Middle Age. He was of a religious turn of mind, without superstition; and the unbroken faith of the mass was like his own. As he went along through his difficult journey, sounding his way, he held fast by the hand of the people, and “tracked its footsteps with even feet.” “His pulse’s beat twinned with their pulses.” He committed faults; but the people were resolutely generous, magnanimous, and forgiving; and he in his turn was willing to take instructions from their wisdom.

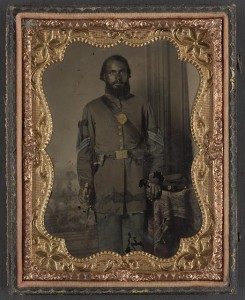

“Unidentified African American soldier in Union infantry sergeant’s uniform and black mourning ribbon with bayonet in front of painted backdrop” (between 1863 and 1865, Library of Congress)

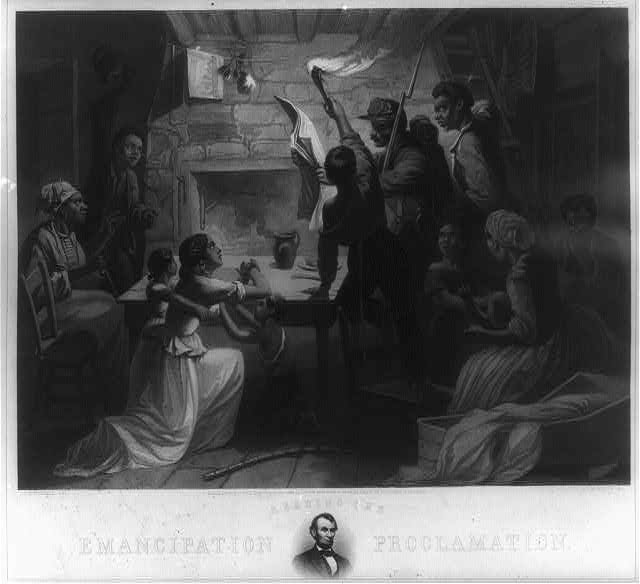

The measure by which Abraham Lincoln takes his place, not in American history only, but in universal history, is his Proclamation of January 1, 1863, emancipating all slaves within the insurgent States. It was, indeed, a military necessity, and it decided the result of the war. It took from the public enemy one or two millions of bondmen, and placed between one and two hundred thousand brave and gallant troops in arms on the side of the Union. A great deal has been said in time past of the wonderful results of the toil of the enslaved negro in the creation of wealth by the culture of cotton; and now it is in part to the aid of the negro in freedom that the country owes its success in its movement of regeneration,—that the world of mankind owes the continuance of the United States as the example of a Republic. The death of President Lincoln sets the seal to that Proclamation, which must be maintained. It cannot but be maintained. It is the only rod that can safely carry off the thunderbolt. He came to it perhaps reluctantly; he was brought to adopt it, as it were, against his will, but compelled by inevitable necessity. He disclaimed all praise for the act, saying reverently, after it had succeeded, “The nation’s condition God alone can claim.”

And what a futurity is opened before the country when its institutions become homogeneous! From all the civilized world the nations will send hosts to share the wealth and glory of this people. It will receive all good ideas from abroad; and its great principles of personal equality and freedom—freedom of conscience and mind,—freedom of speech and action,—freedom of government through ever-renewed common consent—will undulate through the world like the rays of light and heat from the sun. With one wing touching the waters of the Atlantic and the other on the Pacific, it will grow into a greatness of which the past has no parallel; and there can be no spot in Europe or in Asia so remote or so secluded as to shut out its influence.