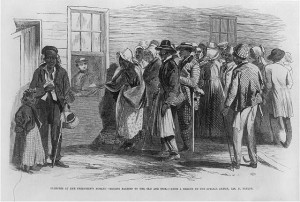

150 years ago today: “President Andrew Johnson appoints General Oliver O. Howard to head the Freedman’s Bureau.”[1]

A May 12th editorial argued that, just as the conduct of black soldiers upset preconceived Southern notions of African-American competence, free black labor could be productive, but only if Southern employers got over their prejudices about the abilities of blacks. Proper training – not whipping – was mandatory. And besides, employers the world over were dealing with and profiting by a much less docile workforce.

From The New-York Times May 12, 1865:

The Negro Question–its New Phases.

Southerners as well as No[r]therners have learned a great many things during this war. They have learned, for instance, that commercial nations are not necessarily unwarlike; that man may be very successful and eager in making money, and yet make a good soldier; that it is an exceedingly exhausting and troublesome job for “one southerner to whip three Yankees;” that cotton is not king, and that slave society is not likely to spread itself over the earth; and though last not least, that negro troops do not run away, and howl when they hear a shot.

These have all been useful lessons; but it is future generations rather than the present one which will profit by them. There is one other which this generation will do well to learn as speedily as possible; it is one by which its own comfort and prosperity will be largely increased; and that is the art of managing negroes as paid laborers, and without the aid of the lash.

There are very widespread indications that the old planters are about to treat us to as striking an exhibition of prejudice on this point as on the others already mentioned. Prejudice on other subjects carried them into the war; and prejudice on this one, if cherished much longer, will prevent their recovery from the consequence of that tremendous disaster. If there be one thing more than another on which your genuine Southerner prides himself strongly, it is his knowledge of the negro, of his feelings, character and capabilities. He laughs the a priori conclusion of the men of other countries about him to scorn. He will never admit that any deductions about the black man drawn from principles of human nature are worth a straw, and always believes himself able to upset them by some bit of plantation experience. When, for instance, people at the North argued from the fact that the black’s being a man, that he could by proper training be converted into a soldier who would stand fire and follow his officers, the Southerners, who of course “knew the negro well,” were prodigiously amused by it. He was to throw down his musket and run the moment he came in sight of the enemy. A Confederate officer was simply to shake a whip to make the knees of a whole battalion tremble. Some of the finest bits of facetiousness which appeared in the Southern newspapers, two years ago, were pictures of what was to happen on the battle-field when our negro regiments were brought into action. Those “sons of thunder,” the Richmond editors, roared over the whole scheme of negro enlistment till their sides ached, and those of their readers as well.

It turned out, however, that they were on this point egregiously mistaken; that the plantation theory of the absence of physical courage from the negro’s composition was totally incorrect; that those who presume that in this, as in other things, he was constituted like other men, were quite right. The negro has made an excellent soldier, and has done invaluable service, and has stood the severest tests of military efficiency with perfect success. It is now positively maintained with equal pertinacity that the free negro will prove as useless in peace as those “who knew him well” were sure he would prove in war. We hear from this “respectable source,” that he will starve sooner than work; that he cannot be educated; or that if he can be, his conceit will be so great that he will go clean daft, and be as useless to himself as to everybody else; that wages are no temptation to him, and that no Southern farmer can possibly conduct his business properly without the power of whipping his laborers. As, however, the labor of free negroes is the only labor the South is likely to have for a long time to come, if not forever, those Southerners who wish to see industry revive, and who are anxious to restore their plantations to cultivation and attempt to reconstruct their fortunes, would do well to avoid acting in this matter, also, on a foregone conclusion. They have proved mistaken in so many things since the war began, that they ought to mistrust their judgment in this one, and try to scrape together for the occasion some of the real philosophic spirit, and experiment on the negro. A little common sense, however, is all that is necessary to teach a man that if the negro really will work at all, it will never do to treat him now as he was treated when a slave. It may be shockingly impudent in him to expect that he shall now be treated with the consideration in manner and language usually accorded to other laborers, but his impudence being one of the facts of the day, all sensible men will take it as it stands, and make the best of it. The demeanor of all servants and laborers toward the employer has changed prodigiously within the last century or two. A master of the year 1700 would be shocked beyond measure by the “airs” assumed by the “lower classes” in all countries in our day. The change may be, and is, in the eyes of many an old Tory, a shocking one; but the work of the world has to go on, and has gone on in spite of it. Employers have had to adapt themselves to the altered circumstances of their work people, and make the best of them as they are. The Southern planters, unless they have made up their minds to starve themselves in order to spite the negroes, must do the same thing. Not being able to secure the services of the faithful, submissive and docile slaves, they must put up with those of “insolent free follows.” We venture to predict, however, that the corn and cotton raised by the latter will sell for just as much, and the fields they plow remain just as fertile as if they had been handsomely “paddled” at the end of every furrow.

According to the Library of Congress:

The University charter of March 2, 1867, designated Howard University as “a University for the education of youth in the liberal arts and sciences.” The Freedmen’s Bureau provided most of the early financial support and in 1879, Congress approved a special appropriation for the University. The charter was amended in 1928 to authorize an annual federal appropriation.

- [1]Fredriksen, John C. Civil War Almanac. New York: Checkmark Books, 2008. Print. page 591.↩

![[Portrait of Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, officer of the Federal Army] (Between 1860 and 1865; LOC: LC-DIG-cwpb-06599)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/06599r-203x300.jpg)