From Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant (in chapters 66 and 67):

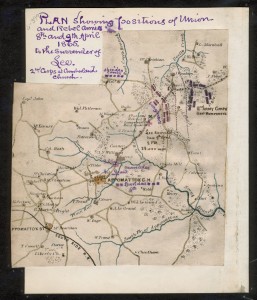

The head of Lee’s column came marching up there [near Appomattox Station] on the morning of the 9th, not dreaming, I suppose, that there were any Union soldiers near. The Confederates were surprised to find our cavalry had possession of the trains. However, they were desperate and at once assaulted, hoping to recover them. In the melee that ensued they succeeded in burning one of the trains, but not in getting anything from it. Custer then ordered the other trains run back on the road towards Farmville, and the fight continued.

So far, only our cavalry and the advance of Lee’s army were engaged. Soon, however, Lee’s men were brought up from the rear, no doubt expecting they had nothing to meet but our cavalry. But our infantry had pushed forward so rapidly that by the time the enemy got up they found Griffin’s corps and the Army of the James confronting them. A sharp engagement ensued, but Lee quickly set up a white flag.

From The Passing of the Armies by Joshua Chamberlain:

Suddenly rose to sight another form, close in our own front, — a soldierly young figure, a Confederate staff officer undoubtedly. Now I see the white flag earnestly borne, and its possible purport sweeps before my inner vision like a wraith of morning mist. He comes steadily on, the mysterious form in gray, my mood so whimsically sensitive that I could even smile at the material of the flag, — wondering where in either army was found a towel, and one so white. But it bore a mighty message, — that simple emblem of homely service, wafted hitherward above the dark and crimsoned streams that never can wash themselves away.

The messenger draws near, dismounts; with graceful salutation and hardly suppressed emotion delivers his message: “Sir, I am from General Gordon. General Lee desires a cessation of hostilities until he can hear from General Grant as to the proposed surrender.”

What word is this! so long so dearly fought for, so feverishly dreamed, but ever snatched away, held hidden and aloof; now smiting the senses with a dizzy flash! “Surrender”? We had no rumor of this from the messages that had been passing between Grant and Lee, for now these two days, behind us. “Surrender”? It takes a moment to gather one’s speech. “Sir,” I answer, “that matter exceeds my authority. I will send to my superior. General Lee is right. He can do no more.” All this with a forced calmness, covering a tumult of heart and brain. …

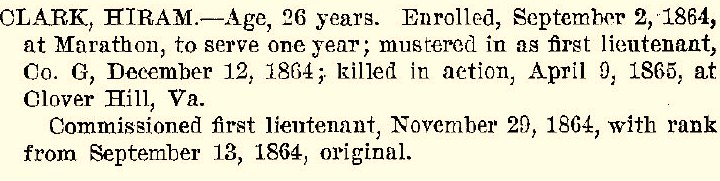

I was doubtful of my duty. The flag of truce was in, but I had no right to act upon it without orders. There was still some firing from various quarters, lulling a little where the white flag passed near. But I did not press things quite so hard. Just then a last cannon-shot from the edge of the town plunges through the breast of a gallant and dear young officer in my front line, — Lieutenant Clark, of the 185th New York, — the last man killed in the Army of the Potomac, if not the last in the Appomattox lines. Not a strange thing for war, — this swift stroke of the mortal; but coming after the truce was in, it seemed a cruel fate for one so deserving to share his country’s joy, and a sad peace-offering for us all.

I’m looking forward to Civil War Daily Gazette’s report on the surrender later this afternoon.

President Lincoln returned got back home from City Point 150 years ago this evening:

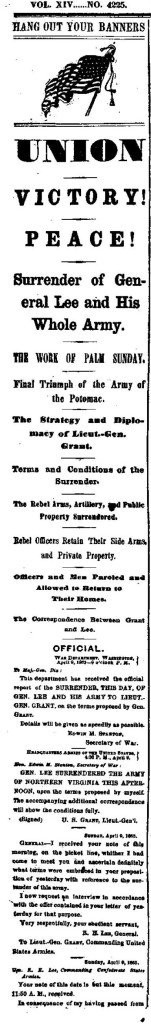

The River Queen reached Washington early on the evening of April 9, and Stanton greeted Lincoln with a momentous telegram from Grant: “General Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia this morning,” at a place called Appomattox Courthouse. Lincoln and Stanton threw their arms around one another. and Stanton, “his iron mask torn off, was trotting about in exhilarated joy,” said an onlooker. Lincoln made his way through the torch-lit streets, already thronging with people, and called at Seward’s home. [and spoke with his bedridden Secretary of State, who had been severely injured in a carriage accident on April 5th.][1]

I’m not sure about the timing on when Lincoln got the word of surrender, and, as you can see in the Times clipping, Grant’s telegram mentioned an afternoon surrender. I don’t doubt that Secretary of War Stanton was joyful. Check out his order for 200 gun salutes to the left.

- [1]Oates, Stephen B. With Malice Toward None. New York: New American Library, 1977. Print. page 458.↩