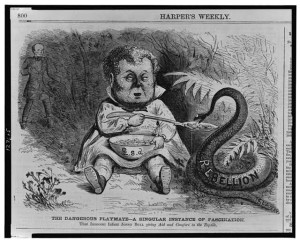

150 years ago today on March 19, 1865 The New-York Times disagreed with foreigners who believed that the defeat of the main Southern armies would only mean the beginning of a protracted guerrilla war. The Times confidently predicted the breaking up of General Lee’s army would be the end of the Confederacy and Lee’s army would soon be broken up.

Foreign Views of the Length of the War.

Our foreign critics still argue that even if the large armies of the Confederates be broken up, the country will still be filled with guerrilla bands, and that then our real difficulties will only begin, in the large spaces of the Southern States, and the impossibility of holding such vast tracts and such a scattered population, in subjection. These views produce no impression here, from our better understanding of the true problems to be solved, and our more accurate knowledge of the constitution and temper of Southern society. If the South were united in their desire for independence, and if their cause were based on immutable principles, we, of the North, would admit the impossibility of subjugating such a country. We might occupy all the strong strategic points with garrisons, and close and hold all the ports; but the people and country would be practically unconquered, and all the immense wealth and the best blood of the United States would be poured out without avail, in the effort to subdue the Confederate States.

But more than one-half of the Southern population are uncompromisingly loyal — the laboring class of blacks, which must number some two and a half millions, and the mountain population of whites, besides great numbers sprinkled about here and there among the disloyal. Large numbers of others are indifferent. They know perfectly that the South never suffered a wrong from the General Government; that submission in North Carolina, for instance, merely means enjoying the same rights and privileges as in Massachusetts, beside bringing after it great comfort and a chance for wealth.

Even if possessed of slaves, they see that the war has made a vast revolution at the South, as well as at the North, and that slavery, after arming the negroes, will be a dead institution everywhere. It is not in human nature to keep on fighting, offering lives, property and comfort, merely for an intangible notion of honor or consistency. Not having been leaders, they have no pride to sacrifice, and they are quite willing to yield, as soon as they are secured of protection.

Accordingly such persons, though having fought long and bravely for the Confederacy, are deserting every day. It is estimated in high quarters that the desertions the past two weeks, from all the armies of the Confederacy, have avenged one thousand per diem.

The masses already feel that they have done enough for honor, and the cause being hopeless, they are ready to submit, when LEE is once defeated. The very sparseness of the population, over such immense spaces, prevents them from uniting for defence, as the people, for instance, in Switzerland or the Caucasus might do, even against an overwhelming force.

But why should they not resort to a guerrilla warfare? We answer that, after the large armies are broken up, nine-tenths of the remaining population will be bitterly opposed to such a horrible and chaotic condition as guerrilla war would bring upon the whole South. Some of their States already have a taste of it, and the “ruthless Yankees” were never denounced half so bitterly as were their own roving bands of plunderers, by Gov. BROWN, of Georgia, or as are the present guerrillas of Mississippi by the rebel press. The truth is, the whole Southern people, black and white, loyal and disloyal, who had a dollar to lose, would rise up to exterminate — to shoot, hang, and burn out such gangs of ruffians, robbers, outcasts and murderers as guerrilla war would create.

Their own people would show no mercy; our Government would execute them by drum-head court-martial, wherever caught, without fear of retaliation. They would be hunted down like wild beasts. Desperate as is the South, she would prefer the Yankee domination to the pandemonium which the guerrillas would spread abroad.

Moreover, when organized opposition was broken down, the Federal Government could afford to leave many of the disaffected districts to their own devices, only protecting our Northern settlers and the loyal from public injury. Society would thus gradually settle itself; and immigration would take the place of armed conquest. The sudden and immense increase of wealth in the South would cause many of the wounds of war to be forgotten, and peace inaugurate itself more easily than many now expect.

On the whole, though the war may drag out a year or more in Texas, or isolated places in the South, we still hold that the breaking up of LEE’s army (soon to take place) will be the end of the Confederacy, and that we have little to fear, either from the vast spaces of the Southern States, or the robbing bands which may survive the main struggle.

Speaking of foreigners, 150 years ago yesterday a Richmond paper stated that the Civil War had changed the relative power of the United States and Great Britain. There might be some grudging admiration for the Yankee war machine as the editorial likened John Bull to a bully. From the Richmond Daily Dispatch March 18, 1865:

Richmond Dispatch.

Saturday Morning…march 18, 1865.

The altered tone of both the English and Yankee newspapers, when they speak of each others respective country, is the most remarkable incident connected with journalism in these latter days. Before this war had revealed the strength of the United States–while they were still entire — the language held by the London Times with regard to them was always slight, often sneering, and, on some occasions, absolutely insulting. On one occasion, it spoke of the ease with which Britain had throttled “the Northern gains, ” Russia, and intimated that it could, at the same time, with all the ease imaginable, administer castigation to Jonathan. Even after the war had actually commenced on this side of the Atlantic, while the parties were marshaling their forces and preparing for the mighty conflict that was so shortly to ensue, the Times indulged its satirical vein, without stint, at the expense of the combatants. After the battle of Manassas it told the Yankees that they had mistaken their calling; that they never could be a great military nation, how great soever might be their aspirations after military fame; that “war was not in their line of business,” and that, to excel, they must take to something else. When Messrs. Mason and Slidell were piratically seized on a British vessel upon the high seas, by a ship belonging to the United States, the tone of the Times was, beyond measure, bold, insolent and defiant.

At the same time, the Yankee press was as obsequious and cringing as the British press was arrogant and domineering. Both are wonderfully altered since that time. The Yankee is now as loud and insulting as he was formerly meek and submissive. The change has not taken by surprise any person who has been accustomed to study the policy of the British. That Government has always been famous for dealing out what it calls exemplary justice upon culprits whom it believes unable to help themselves. Let not such hope to escape the lash of British vengeance. Greece, or Brazil, or any of the little States on the Continent — such as Denmark, for instance,–cannot hope to escape upon any conceivable pretext whenever it may be so unfortunate as to incur the wrath of the British lion. It is only strength that secures impunity from that magnanimous animal. Even now the New York Herald is calling upon the British Queen to revoke her proclamation of neutrality — that is, we suppose, to take part with the Yankees in their war upon this country. We do not see why this should not be done. It would be perfectly consistent with the whole conduct of Great Britain throughout the war. Should Ambassador Adams choose to demand it, a good-natured, easy soul like Russell could hardly refuse so small a favor to his amiable ally, after having already granted him so many others. He has already placed Canada at his disposal; he has but to stretch out his hand to grasp it. Why refuse anything, when so much has already been given, we ask again?

We sometimes feel disposed to be a little astonished at the facility with which Great Britain has been brought to play second fiddle in this concert of the nations. Who that lived a century, or even a half century ago, would have believed it possible that such a thing could ever happen. But we suppose it is with governments as with individuals: the greatest bullies are always the first to succumb when real danger presents itself.