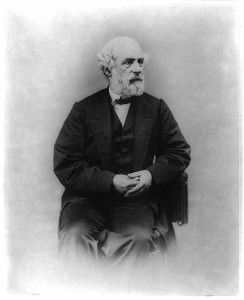

I guess desperate times really do call for desperate measures. In its Monday morning editorial the Dispatch calls for the Confederate Congress to let General Lee use slaves as soldiers in exchange for their freedom. As you can read, the editorial uses the “fight fire with fire” argument and respects General Lee’s opinion on the subject.

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch February 20, 1865:

Negro soldiers.

At the beginning of this war there was an important question to be solved by its progress, and that was: Could the South prosecute the struggle with out embarrassment from the existence of four millions of human beings within her limits who were not amenable to service with arms in the field. Generally, it is considered necessary to the defence of an invaded nation that all the men between certain ages, capable of bearing arms, shall be amenable to service in the field. Here, the black constituted a distinct class, and it was supposed by many that, as they produced the necessaries of life, they would sustain the public defence more successfully in that way than if sent in the field to fight. But nations that are hard pressed by powerful invasions leave the production of the necessaries of life to that part of the population which is under and over the conscript ages. Could we pursue a different course? Could we set apart a large population, irrespective of age, to the pursuits of production of the ne was doing force? However that question might have been decided under other circumstances, the employment by the enemy, in making war upon us, of that very class of beings we intended to exclude from the field, forces upon us the necessity of placing them in the front to defend the country. We must fight the negro with the negro, whatever we could have done had the enemy forborne to employ him. This necessity is, of course, disagreeable, as is proved by the evident reluctance with which we have entered upon the discussion. Therefore, whatever the differences of opinion hitherto on this subject, all parties are now willing to leave the solution to the sound, practical judgment of General Lee. He is known to be earnestly in its favor, and we want no other endorsement. We hesitate not to say that the time has come when negroes should be employed as soldiers, and that they should be offered their freedom, for that purpose, upon entering their availability as soldiers, of their courage and efficiency under a proper system of discipline — such a system as General Lee, at once firm and humane, would inaugurate. It is better to liberate two hundred thousand negroes, and to put them in the army, than to run the risk of losing all. We would rather sacrifice them all, and make emancipation universal, than hazard the independence of the Confederate States. If we fail, we lose everything, property of every kind, and our own independence. Let Congress give heed to the counsels of General Lee. In pursuance of the universal public sentiment, it has called him to the chief command of the armies of the Confederate States. But of what avail will be that action if Congress does not clothe him with the means which he deems necessary to success? For this purpose, he should have carte blanche to raise the forces he desires upon such terms, and in such a way, as he deems expedient. There is no time for delay. If Congress grasp the subject with the promptness, energy and breadth of statesmanship that it demands, the country issued.

But, also in desperation, Lee’s Adjutant, Walter Taylor, wrote his girlfriend 150 years ago today and wished the South had a more vital general than his boss to save the South (at least as general-in chief, I think he might be saying):

Edge Hill

20 Feb. ’65

This has been a day of considerable bustle, my dear Bettie, and even now there are some incomplete matters claiming my attention. I will not longer defer my letter, however, for it is impossible to say what a day may bring forth in these uncertain times. Truly affairs are becoming quite exciting, are they not? If somebody doesn’t arrest Sherman, where will he stop? Where are those who leave Richmond to go? [concern about family and friends near Charlotte and in Richmond] No place promises security that I can see, except immediately with the army. … You had better mount your horse and travel along with me until the uncertainty has passed and our affairs are once more straightened out. They are trying to corner this old army like a brave old lion brought to bay at last. It is determined to resist to the death and if die it must, to die game. But we have not yet quite made up our minds to die … Our people must make up their minds to see Richmond go, to see all the cities go, but must not lose spirit, must not give up. … Oh for a man of iron nerve and will to lead us! We need a strong hand now. There can be no trifling, no halting or hesitation now without ruin. Our old Chief is too law abiding, too slow, too retiring for these times, that is to dare & do what I deem necessary, but nevertheless he is the best we have, certainly the greatest captain and in his own safe & sure way will yet, I trust, carry us through this the greatest trial yet. … [ordered to be ready for a march] … the army will retain its position still a time longer, the General in Chief may soon bid a temporary adieu and repair to another scene of excitement. …[1]

- [1]Tower, R. Lockwood with John S. Belmont, eds.Lee’s Adjutant: The Wartime Letters of Colonel Walter Herron Taylor, 1862-1865. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1995. Print. page 224-225.↩

![Unidentified African American soldier in Union uniform and Company B, 103rd Regiment forage cap with bayonet and scabbard in front of painted backdrop showing landscape with river] (between 1863 and 1865; LOC: LC-DIG-ppmsca-36988)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/36988r-239x300.jpg)