boon to the Southern economy? (“Fort Fisher, N.C. View of the land front, showing destroyed gun carriage in second traverse” Library of Congress)

150 years ago today Richmond’s Dispatch was full of Northern accounts of the the fall of Fort Fisher. The editors spun the resultant closing of the port of Wilmington as economically advantageous:

The fall of Fort Fisher, and the subsequent closing of the port of Wilmington, though deemed disastrous in a military point of view, has necessarily diminished the value of gold by lessening the demand. The public are not aware of the vast amount of influence exercised over the gold market by the operations of the blockade-running at Wilmington. From twenty thousand to one hundred thousand dollars in gold were required to meet the weekly demands of the buyers, and nearly all the gold drawn from the market flowed out through that channel. On Mondaymorning last, one thousand dollars in gold were sold at sixty- two and a half in Confederate money for one in specie. Two hours afterward came the news of the fall of Fort Fisher. Immediately gold rose to seventy-one, and for several days continued to advance, through the combined influence of the brokers, till it reached seventy-six; but here it stopped, and has since had a steady downward tendency.

So far, then, as the monetary affairs of the Confederacy are concerned, our prospects are brighter than for many days past; and should our currency continue to improve under the wholesome treatment now advised and in contemplation, our prospects in other points of view cannot grow worse.

In another section of the paper, after discussing slavery statistics, the editors wished the Yankees would just go home because the war had become so monotonous. They wanted to be able to report on other things. From the Richmond Daily Dispatch January 21, 1865:

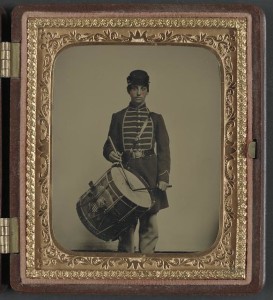

those nauseating Yankee drums (“Unidentified soldier in Union uniform and Massachusetts belt buckle with drum” Library of Congress)

We devoutly wish there was some other subject to write about except Yankees and Lincoln. We are as sick and tired of the disgusting monotony as any one can well be. Even roast beef and plum pudding would lose their charms if one were compelled to dine on them every day in the week, and every week in the year, for four years, much more pork and beans, and codfish and potatoes. We are nauseated with the whole subject of Federals and flank movements, ditching and entrenching, bombshells, iron-clads and torpedoes. We are disgusted with the name of every prominent man in the United States, not simply because they are grand rascals, but because they have become tedious. To have to indict the same thieves at the Old Bailey every day in the week; to see the same ugly, vicious faces peering over the dock every day of the year, is equal to being Mayor of the city of Richmond. Nothing is so offensive as a stale rogue. The interest that villainy at first arouses wears off by repetition. Even the inventive genius of the Yankees fails to keep up our curiosity. The novelty of both their crimes and absurdities has disappeared, and they can no longer produce a sensation. They have made arson, robbery and murder so common that the newspapers, in order to keep up with these performances, have become little better than Newgate Calendars. We wish, just by way of variety, they would become decent and civilized, and relieve us from a bore which has become more intolerable than the bores of their cannon. We wish they would all go home, if only to give the newspapers something else to write about. Only to think of four long years, in which every article, every day of the year, is about war and Yankees.

We appeal to them as fellow-beings on two legs, and having the same external aspect of humanity as other men, will they not begone and let the newspapers alone? How would they like to be invaded in this way, and have nothing to write about but drums, trumpets and gunboats? We say nothing of bloodshed, burning, hanging, confiscation and the like. It is a fearful thing to have only one subject to write and talk about for four years.