As a Richmond paper tallied the military balance sheet for 1864, the conclusion was inescapable – the South had had a great year.

From a Seneca County, New York newspaper in 1864:

The Military Account Current Between North and South for 1864 – Alleged Large Ballance [sic] in Favor of the Rebels.

The military balance sheet for 1864 will be greatly in favor of the Confederate states. If results had only shown an equipose [sic] as between the two beligerants [sic], the advantage would have been nevertheless largely with us; because, with the enemy, mere failure is disaster and defeat, while to us to hold our ground is a victory. They have set out to accomplish a great positive result. It is not to be attained by defensive lines and cautious policies and negative advantages. These are all on the side of their adversaries. When they make no advance, they are retrograding. Delay does not merely disappoint and dispirit them, it undermines their strength. Each day they become weaker, so severely have they strained their resources, and so vast and rapidly increasing is the debt they have incurred.

Little Mac could have gotten this far (“General Ulysses S. Grant at City Point in 1864 with his wife and son Jesse.”)

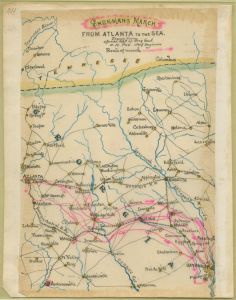

But we have done more than maintain ourselves. We have inflicted positive as well as negative blows. In Virginia we have lost nothing, while we have destroyed a host of our enemies. Grant might probably have gained his present position as a starting point for his campaign. He has been driven there by necessity; but his army has melted away in the Wilderness, and at the close of the campaign, with nothing accomplished he is begging for men to fill the places of the multitude he has lost. In the trans-Mississippi States, we have gained astonishly [sic], and the invaders have been almost entirely destroyed or driven off. In Georgia, the campaign is still afoot, and the result undecided, but we have hope of closing the year without damage, as compared with its commencement.

While such are the military results of the year now closing, as to its leading operations, are enemies have, indeed, constantly claimed victories. Secretary Stanton’s war bulletins, if the fourth of what they declared were true, have announed [sic] successes sufficient in magnitude and number to have ended half a dozen wars; but the striking commentary upon them all is, that his armies have made no advance, or have been driven, and he is farther from conquest now, when the sky is again leaden and wintry, than when the spring of 1864 first gave us its smiles. The deceptions which he has practiced in the particular instances are now made manifest and palpable by the aggregate result. As no array of victories could add up a defeat, so the unfavorable position in which President Lincoln finds his fortunes, at the close of the campaign, exposes the frauds by which his people have been constantly assured of their prosperous progress.

ROBBING THE CRADLE AND THE GRAVE.

SOUTHERN MATRON. “Well, father, you’ve got to go, I see. JEFF DAVIS had better take little PETE along too. You’d both be jest the age for two soldiers. You’re sixty-nine years old, and he’s one. That’s zactly thirty-five on an avridg.”

All have not been deceived. There are some who, convinced of the folly of his undertaking, and the impossibility of subjugating a people so numerous, and in a territory so vast, have scrutinized the stories of victory and triumph, and compared them with the developments that followed. They have seen great drafts follow on the heels of great victories. They have seen the demoralized and despairing rebels, after having been scattered to the winds a dozen times, swiftly falling upon their foes and inflicting defeat. They have been promised the immediate capture of Richmond times innumerable; but they have never seen it captured. “More men – five hundred thousand more men” – is the word they get from Grant after a series of battles, in every one of which he had inflicted enormous losses and a crushing defeat on the rebels, and which had driven them to the last ditch and to a robbery of the cradle and the grave. They want to hear him announce the fall of Richmond, but instead of this there comes the demand for vast re-enforcements and renewed supplies.

Hannibal’s enterprise against Rome was very strongly opposed by Hanno, a prominent Senator of Carthage. The wonderful successes which at first attended the Carthagenian arms produced no change in his sentiments. After the great victory at Cannae, Hannibal sent Carthage a bushel of gold rings, taken from the fingers of the Roman nobility that fell in the battle. He accompanied his glowing accounts of his triumphs by a request for re-enforcements. Carthage was thrown into an ecstasy of joy by the glad news, and Hanno was reproached by a Senator of the opposition party who asked him if he still opposed Hannibal and the war. Hanno answered “that the victories they vaunted of, supposing them real, could give him joy only in proportion as they should be made subservient to an advantageous peace; but he was necessarily of the opinion that the mighty exploits of which they boasted so much were chimerical and imaginary. [‘]I have twice seized the enemy’s camp, full of provisions of all kinds; send me provisions and money.’ – Could he have talked otherwise had he lost his camp? He tells us the Romans have made no proposals of peace, from which I perceive that we are no farther advanced than when Hannibal first landed in Italy,” Thus spoke Hanno, and his conclusion was that Hannibal should be re-enforced, and that the war should be abandoned. – Richmond Sentinel.

The Sentinel did not appear too concerned about the idea of total war – it mentioned the trans-Mississippi but not the Shenandoah Valley.

The political cartoon appeared in the December 17, 1864 issue of Harper’s Weekly, which we can read thanks to Son of the South.

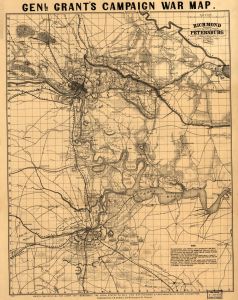

![agnus' historical war map. One hundred & fifty miles around Richmond. (New York, Washington, Charles Magnus, [1864] ; LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/99446360/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/150milesRichm-1024x923.jpg)