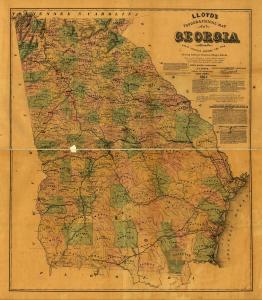

he’s somewhere in here and maybe being resisted (1864 map from surveys before the war; Library of Congress)

A pretty subdued Monday morning editorial from Richmond. The paper isn’t sure where Union General Sherman and his army are headed in Georgia, but the editors “should not be surprised if they met some resistance in this march.”

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch November 28, 1864:

Monday morning…November 28, 1864.

We do not know where Sherman is, nor do we pretend to know. The Yankees know all about him, and they make no mystery of their knowledge. How they got it, seeing that he is cut off from all telegraphic communication, we are not to inquire. We presume, however, that he has a corps of carrier-pigeons, drilled for the occasion — knowing birds, that can distinguish between a Yankee and a rebel, and never make the mistake of lighting in a camp of enemies when bound for a camp of friends. To some such method of communication the knowledge acquired by the Nashville correspondent of the Chicago Times, who dates on the 16th from Nashville, must be ascribed. He could have obtained it in no other way, unless he be gifted with the “second sight.”

He tells the Times that the design of moving through Georgia originated with General Sherman, and that the Secretary of War approves of it; that he takes with him the Fourteenth, Fifteenth, Sixteenth and Twentieth corps, and eight thousand cavalry–fifty or sixty thousand men in all; that this force is amply sufficient for any purpose — that the rebels have three thousand men at Savannah, and about the same number at Charleston, besides militia, which he does not value highly; that there are no others to meet him without weakening Lee, as Hood could not overtake him if he were to try. Besides, the latter has as much as he can attend to, watching Thomas. Sherman is to move in two columns, one by way of Macon, and the other direct for Augusta, at which latter place the two will concentrate. Three points, then, present themselves, all equally at the mercy of the irresistible Sherman: Savannah, Beaufort and Charleston. Sherman will select Savannah — the correspondent is certain of it, and he gives his reasons. Savannah, cut off from all communication, will be useless to the rebels. Charleston can be cut off by moving down the road to Branchville, twenty or thirty miles to the west. Beaufort is already in Yankee possession, and there are supplies and shipping there in any quantity.–Circumstances may intervene to change Sherman’s intention; but that he now means Beaufort is certain. He will not go there, however, until he has completely isolated Charleston and Savannah.

The correspondent then points out the immense advantages of this route. Macon and Augusta are both manufacturing towns. Jeff. Davis, in his speech at Macon, said Augusta furnished powder enough for the whole Confederacy. But the chief advantage consists in the destruction of communications, whereby it is expected to isolate the army of General Hood, separated as thoroughly from Lee as the troops west of the Mississippi are. Savannah will be no longer valuable as a blockade-running port, Charleston will be cut off, and Sherman’s army of 55,000 men will be on the seacoast, so that they can be transferred to Grant or Sheridan, or, after recruiting, they may be moved through Central South and North Carolina, “utterly annihilating every railroad by the way, and thus making Virginia the grave of the rebellion. “

A very splendid programme this, but not half so splendid as Grant’s of last spring. There is one element which the Yankees never take in when they make paper campaigns. They always sketch marches in which there is to be no resistance. Now, we should not be surprised if they met some resistance in this march.