Oh, to be iron-clad from head to foot. … but we drone on.

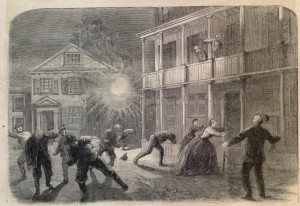

The Yankees are still shelling Charleston. In this correspondence concerning the night of September 30th, some civilians were wounded, and, while the writer was amused by the sight of blacks fleeing the bombs, he admitted that the thought of the shells being directed at him “caused a cold chill to run through my veins.” Also, Yellow Fever was on the rise in the city.

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch October 15, 1864:

The shelling of Charleston — a night of horror.

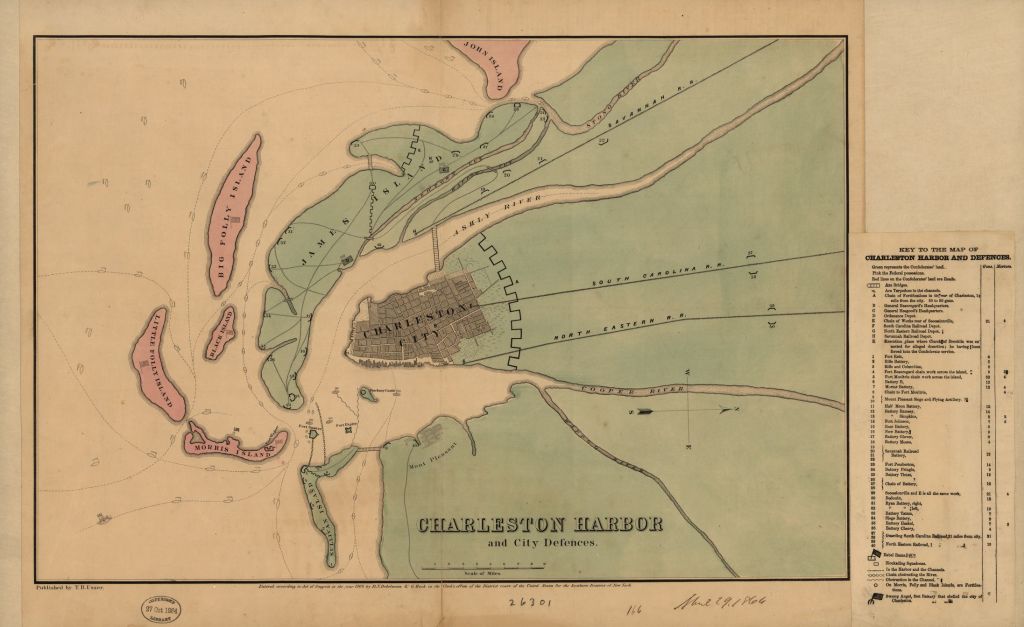

A correspondent of the Macon Confederacy, writing from Charleston on the 30th, gives an account of the cruel shelling of that place, in the corporate limits of which there are not probably a dozen Confederate soldiers.

Wednesday night will long be remembered by the residents of this city as a night of horror. The shelling of the place had been almost continuous and rapid on Monday and Tuesday, but the bombardment of the last forty-eight hours has exceeded it all. On Tuesday evening I counted four shots within eight minutes, and thought it remarkably rapid firing; but the cannonading Wednesday night beat even that. It commenced a little after six o’clock and lasted until ten–the shells averaging forty and forty-five to the hour. The firing is said to have been from four guns, but I think more must have been used, as any one at all acquainted with heavy artillery practice knows that it takes considerable time in the loading and firing of heavy ordnance.

That the enemy have mounted additional and heavier pieces is evidenced from the fact that the shells were thrown in a part of the city hitherto considered safe and beyond the reach of these devilish missiles. Where that neighborhood is, I shall not be so indiscreet as to mention for the information of the enemy.

Much damage was done to buildings and considerable injury to persons — the family of one of our oldest and most respectable merchants, consisting of a lady and four children, were all wounded by the explosion of a percussion shell in the room in which they were seated at tea. The lady had her collar bone broken, the children were less seriously hurt. During the day, one man had an arm taken off, and another lost a leg from the shells. Up to this writing, I have heard of no loss of life from the bombardment of the last forty-eight hours.

Had it not been a matter of life and death, some of the scenes witnessed, by the flight of the darkeys from the shelled district, would have been ludicrous and mirth provoking.

Many old wenches passed the window at which I was seated, loaded down with every conceivable useful and useless article of household plunder, with their young ones screaming and tugging at their skirts. Others, with more maternal feelings, abandoned all their kitchen goods and bore off their Scotty picaninnies alone. I noticed one of the latter loaded down with no less than three–two in her arms and one riding on her back. One old African, in hobbling past, cordially, but irreverently, wished that the Yankee who invented those big guns “was in hell-fire, and the d — d rascals dat was firing dem, too.”

It is a singular idea, but no less true, that the negroes hereabouts seem to think themselves a doomed race, so far at least as shells are concerned; but they bid defiance to fate on this occasion by leaving at the first fire. I have heard of but few whites leaving the neighborhood.

Had a fellow been iron clad or bombproof, top and bottom, the sight would have been a grand and imposing one; but when my attention was even at its height the thought that the flight of these fiery monsters might be turned in my direction caused a cold chill to run through my veins.

The firing ceased at 10 o’clock, and was not renewed until 8 the next morning, and was kept up steadily but slowly all day, the shots not exceeding eight to the hour.

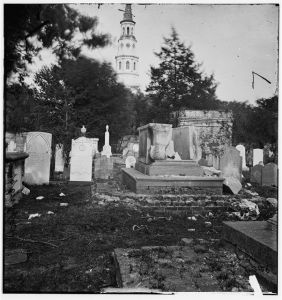

The Yankees war not only with women and children, but even with the dead. Several shells fell on Tuesday night in the graveyard of Trinity (Methodist Episcopal) Church, tearing up the graves and demolishing the tombstones of the sacred dead. They may have been chance shots. I think otherwise, and that they were but following the hyena-like instincts of their projectors.

The yellow fever, I am sorry to say, is on the increase. It is now among our German population, with whom it is generally very fatal, as all previous yellow fever seasons has abundantly proven.–Prayer for its abatement was offered up in several of the churches last Sunday.

The Charleston Courier adds to the above this paragraph:

The enemy renewed their fire upon the city rather feebly Thursday morning.–Some thirty-three shots were fired up to six o’clock Thursday evening. No further casualties were reported, but several very narrow escapes made. In one house the family but a moment previous to the entering of a shell had retired to the dining-room, when the sitting-room was struck, making a complete wreck of the room and contents. A prayer book on a side-table appeared to be the only article that escaped destructive. It was opened at the 49th Psalm, commencing with: “Deliver me from mine enemies, O. my God; defend me from them that rise up against me. Deliver me from the workers of iniquity and save me from bloody men.”

It wasn’t just civilians. 150 years ago prisoners of war were purposely exposed to the bombs flying through the Charleston air.During 1864 Confederate General Samuel Jones housed Union prisoners in parts of Charleston within range of the Yankees to try and reduce the shelling of civilian areas. Union General John Foster eventually retaliated by putting approximately 600 rebel prisoners on Morris Island – in the path of both Confederate and Union shells. You can read all about this episode in a very good article at HistoryNet. The mutual exposure of prisoners ended 150 years ago this month:

General Jones’ threats to put Union prisoners on the ramparts of Fort Sumter never materialized, and on October 8 the Union captives in Charleston were removed to cities farther inland. The Southern captives’ ordeal continued, however, until October 21, when, after 45 days of exposure to shellfire, they were finally taken out of their miserable pen and transferred to Fort Pulaski at Savannah, Ga.