From a Seneca County, New York newspaper in September 1864:

Terrible Suffering of Federal Prisoners.

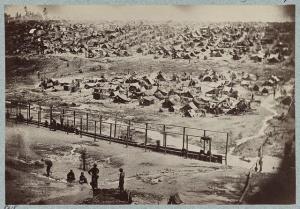

The public mind is becoming very much disturbed at the terrible condition of the Federal prisoners now in the hands of the enemy. Among the passengers by a late arrival of the Steamship Arago from Hilton Head, S.C., are four exchanged prisoners, commissioners appointed at a monster meeting of the 35,000 Union prisoners confined in Camp Sumter, Andersonville, Ga., to wait on the President at Washington, with a petition praying that immediate action be taken to terminate their sufferings, either by parole or exchange. When the commissioners left, the deaths reached 143 per day. The deaths since the opening of the prison on the 25th of February last, up to the 31st of July were 6,800. In the month of July alone the deaths were 2,180, including 550 from scurvy.

The memorial to the President adds that upwards of four hundred of the prisoners are maniacs, wandering through the camp, their minds having given away by the fearful prospect – despairing of ever being either exchanged or paroled. Thousands of these prisoners have spent from eleven to fifteen months in Belle Island and Camp Sumter, without any word of hope reaching them that they would be exchanged. Indeed, it is even asserted, that so terrible is the agony of mind endured by the prisoners, that many of them are shot down weekly on the “dead line,” where they rush and invite the guards to kill them, in order to terminate their sufferings.

This is a terrible picture, and it ought to arouse the public mind to such a degree as to compel immediate efforts for the release of the brave men unnecessarily and needlessly held in Southern prisons. It is through the bad faith of the administration of Mr. Lincoln, that these men are not paroled or exchanged. Time and again the rebel authorities have sought to affect a fair, equal and honorable exchange, but in vain. Because Mr. Lincoln could not enforce upon the rebels the doctrine of negro equality – and compel them to recognize and treat as equals the negro slaves who have escaped from them, and who return as prisoners taken in arms against their lives and property, it was authoritively announced by Mr. Solicitor Whiting that no more exchanges would be made. And it is for a few hundred negroes that the 35,000 white men at Andersonville are suffering and dying. The settlement of the controversy as to the status of the negro must take place before the tens of thousands of Federal prisoners now dying in Federal prisons can be released. The 35,000 white prisoners at Andersonville must suffer and die because the rebels do not see fit to give up a few hundred blacks. Will the course of the administration satisfy the 35,000 family circles which are filled with mourning over the fate, known or unknown, of their beloved ones at Andersonville? We think not. We think that this last dreadful sacrifice on the altar of negro equality will prove too great a strain upon the patience of the North. It is only through the downfall of the Lincoln dynasty, that we can hope for the release of the remnant of these unhappy men.

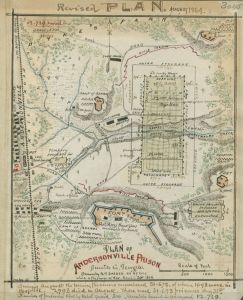

According to the National Park Service Confederates were amenable to exchanging the black prisoners in late summer 1864, but General Grant opposed the idea of mass exchanges because he did not want to increase the manpower available to the Confederate armies. Large scale exchanges did resume in the winter of 1864-65. The New Georgia Encyclopedia explains that as Sherman advanced through Georgia in the fall of 1864 Andersonville prisoners were transferred to other prisons. As a matter of fact, Robert Knox Sneden who drew the map in this post and who managed to survive the prison’s horrors from his arrival on Leap day, left the prison on September 17th on a train to Savannah [1]. In December there were about 5,000 inmates at Andersonville.

150 years ago this week Southerners weren’t too happy about the condition of some of their returned prisoners. From the Richmond Daily Dispatch September 24, 1864:

Arrivals by flag of truce.

–Four hundred and sixty returned sick and wounded Confederate prisoners from the North arrived in this city from Varina at 8 o’clockThursday night. The majority of them were in a most deplorable condition, and it was heart-sickening to witness their sufferings as they lay in the various hospitals yesterday. If it is possible for our Government to obtain the release of the Confederate prisoners confined in Northern bastiles, no steps should be left unturned to accomplish it, for the appearance of those who have lately arrived here, and the statements which they make with regard to their treatment in Yankeeland, shows conclusively that it is the object of the Yankee Government to adopt every means in their power to so impair their health as to prevent them from ever being able to perform service again.

Among the number who arrived were Bernard G. Crouch, of this city, and Rev. Dr. Armstrong and family, from Norfolk, Virginia. Dr. Armstrong was sentenced by Butler to labor on the Dry Tortugas during the war. By what means he obtained his release we have not been informed.

Thirteen of our prisoners died on the passage from Fortress Monroe to this city, and, in the opinion of the physicians now attending them, a great many others will not recover.

- [1]Sneden, Robert Knox. Eye of the Storm: A Civil War Odyssey. New York: The Free Press, 2000. Print. page 258.↩