In the same issue that featured articles on Cold Harbor and the Georgia campaign and startling images of starved Union prisoners, the June 18, 1864 Harper’s Weekly (at Son of the South) published a poem by a member of President Lincoln’s inner circle:

WHEN THE BOYS COME HOME

THERE’S a happy time coming,

When the boys come home.

There’s a glorious day coming,

When the boys come home.

We will end the dreadful story

Of this treason dark and gory

In a sunburst of glory,

When the boys come home.

The day will seem brighter

When the boys come home,

For our hearts will be lighter

When the boys come home.

Wives and sweethearts will press them

In their arms and caress them,

And pray God to bless them,

When the boys come home.

The thinned ranks will be proudest

When the boys come home,

And their cheer will ring the loudest

When the boys come home.

The full ranks will be shattered,

And the bright arms will be battered,

And the battle-standards tattered,

When the boys come home.

Their bayonets may be rusty,

When the boys come home,

And their uniforms dusty,

When the boys come home.

But all shall see the traces

Of battle’s royal graces,

In the brown and bearded faces,

When the boys come home.

Our love shall go to meet them,

When the boys come home,

To bless them and to greet them,

When the boys come home;

And the fame of their endeavor

Time and change shall not dissever

From the nation’s heart forever,

When the boys come home.

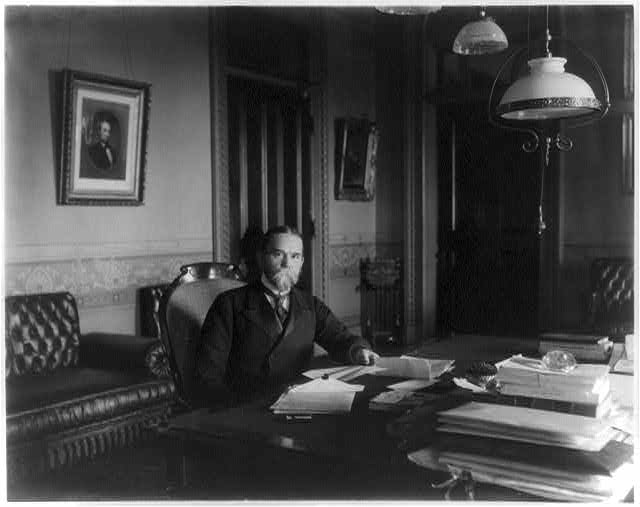

JOHN HAY.

EXECUTIVE MANSION, WASHINGTON.

An editorial on the same page lauds Secretary of War Stanton and Generals Grant and Sherman for the matter-of-fact truthfulness of their reports:

PUBLIC CONFIDENCE.

THE good sense of the Secretary of War in issuing daily bulletins of the campaign can not be too highly commended. It is another proof of the fact that we have settled down to war in earnest, and that the country wishes to know only the truth. The good result of the system is seen in the deaf ear which we all turn to the mere rumors of the street and bulletin boards, and in the question universally asked upon every fresh statement, ” Is that official?”

This happy result is greatly enhanced by the public confidence in the perfect truthfulness of the reports of Generals GRANT and SHERMAN. There is no rhetorical clap-trap in them. General GRANT drives the enemy to cover, and he does not instantly telegraph that he is pushing them to the wall; he says only, “it is no decisive advantage,” and the country is calm because the General is. General SHERMAN tells what he has done, not what he is going to do, and the country, looking at the map, is satisfied.

Every body understands that the task before GRANT and SHERMAN is, as the President says, one of magnitude and difficulty. In the case of GRANT it is easy to see that the work would have been easier could he have beaten LEE upon the Rapidan or at Spotsylvania, because then he would have been spared the necessity of besieging Richmond. Yet great and difficult as the task is, there is a public tranquility which springs from profound confidence in him and in the ultimate success of the cause. There are people who occasionally shake their heads and whisper, ” Dear me, if GRANT should fail !” Well, if he should, who could put another army in the field first ? And as for spirit, for resolution, the mind of the country was never so firmly fixed in its purpose of suppressing the rebellion at any cost as it is at this moment.

![Battle of Spottsylvania [sic ( [Boston] : L. Prang & Co., 1887.)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/04038r-300x217.jpg)