going to hurt me more than you?

From the June 11, 1864 edition of Harper’s Weekly at Son of the South:

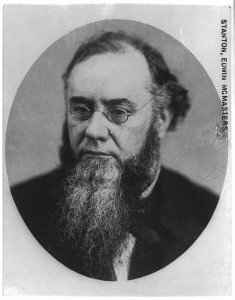

Also 150 years ago this week, a Richmond paper noticed that Union Secretary of War Stanton’s telegrams to General Dix in New York seemed to leave out some important information. From the Richmond Daily Dispatch June 11, 1864:

Saturday morning…June 11 1864

Sta[n]ton’s dispatches.

We think it may be asserted without fear of contradiction, that Stanton is the first war minister on record to whom was assigned the duty of lying for the benefit of his master. In what estimation that master must hold his services when the duties he puts him upon are a disgrace to him, or would be were he other than he is, we care not to inquire. Suffice it to say that he suits the office, and the office suits him. If he takes a pleasure in inventing lies he does it with considerable ingenuity. He is master of all kinds of lying. He can suppress the truth with as much skill as he can invent a falsehood. The following paragraph in one of his dispatches is a remarkable specimen of the two styles — the suppressic veri and the suggestio falsi. We do not know that we ever saw the two so happily blended in a single paragraph:

Washington, June 5th–1 P. M.

Major General Di[x]:

A dispatch from Gen Grant’s headquarters, dated half-past 8 o’clock last night, has been received. It states that about seven P M yesterday (Friday, 3dJune,) the enemy suddenly attacked Smith’s brigade, of Gibbon’s division. The battle lasted with great fury for half an hour. The attack was unwaveringly repulsed.

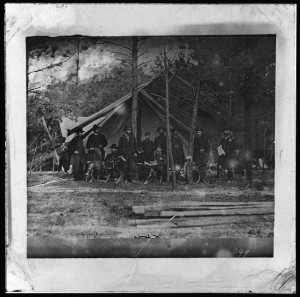

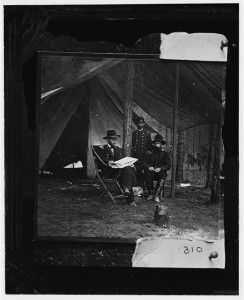

“General Grant, Lt. Col. Bowers, and General Rawlins at Grant’s headquarters, Cold Harbor” (June 11 or 12, 1864)

Not one word of the events of that bloody Friday morning. If the Yankee nation ever learns that at five o’clock on Friday, the 3d of June, 1864, Grant made a furious assault upon our lines, and after a murderous conflict of five hours duration was finally repulsed, with a loss of at least 15,000 men; that he left his dead and wounded in our front for days, not daring to attempt to remove them openly, and basely refusing to send a flag of truce lest it should be construed into an acknowledgment of defeat; and that those wounded men lay there until many of them died, and those dead until the stench from their bodies became intolerably offensive, it will be through no fault of Secretary Stanton or General Grant. If the truth can be suppressed by these worthies, suppressed it will be — this attempt to do it proves that — for the ignoring of a battle in which 15,000 men were slain or wounded, is the most astounding feat of that sort on record. The rest of the paragraph is quite in character, although not upon so large a scale. There the lie direct is conspicuous. Gen. Lee says that the attack there alluded to was repulsed with ease, and everybody who was in the fight says that the slaughter of the enemy considering the extent of the front, and the numbers engaged, was even more terrific than it was in the morning. With regard to the attack upon Heth’s division, the language of Gen. Lee is quite as emphatic, It was repulsed with the utmost ease, and the Yankees took no rifle-pits.

It is to be hoped that Stanton puts into Grant’s mouth such words as he thinks proper. We can hardly believe that Grant himself, who is a soldier, though a most butcherly and inhuman one, would descend quite so far. But what a commentary do these telegrams form upon that Government which requires them, and upon the necessities of that same Government, when it does require them? It is obvious that the truth cannot bear the light, and for this reason it is kept studiously concealed. What is such a Government worth?

Napoleon was accused by the English newspapers of publishing lying bulletins.–The accusation we believe to have been false, except in so far as he was wont, in common with all other commanders, to exaggerate the strength of his battalions before a battle, in order to deceive the enemy. The result, in every instance, at least argued strongly in favor of his having told the truth. When he published that he had taken 60,000 prisoners at Ulm, he had already destroyed the Austrian army. When he claimed to have captured 30,000 at Austerlitz, his foot was upon the neck of Francis, and Alexander escaped capture only by his permission. When he announced the capture of 40,000 at Jena, he had just crushed the Prussian Monarchy to the earth. When he said that the battle of Wagram had “deprived Austria of 60,000 warriors, ” he was in pursuit of her shattered columns, and a few days after concluded a treaty which stripped her of immense territories and 5,000,000 of subjects. If he lied, he lied with strong circumstances to support him. If he overestimated the loss of his enemy on the field of battle, he did not do it so far as to make it incommensurate with the results. The Yankee Generals have been said to copy after him; but if they do, they only copy what his enemies called his exaggerations. It is easy enough to copy a lie, and not very difficult to lie without a copy. Napoleon had results to show in answer to all charges of lying.–What has Grant to show, or Stanton for him? Immense loss of men, and no progress in obtaining the objects of the campaign. Richmond is as inaccessible to Grant at this moment as it was when he was fifty miles off. He has not carried a single position, and he has been repulsed in all his attacks.

The telegram referenced by the Dispatch was published on the front page of the June 6, 1864 New-York Times in an article which did mention the heavy Union losses.

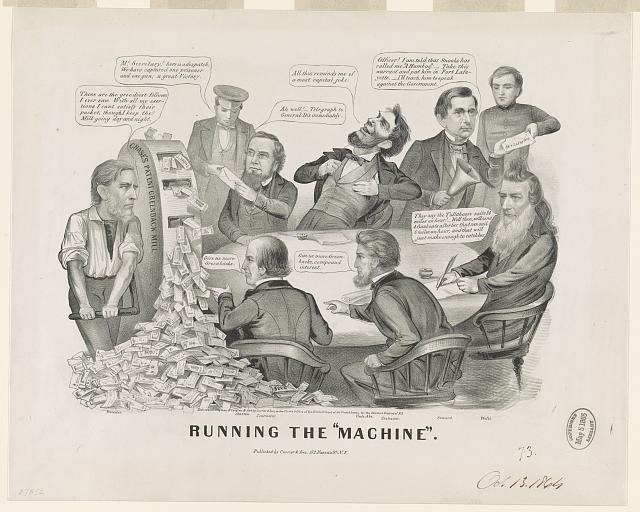

The following political cartoon from the Library of Congress mentions Stanton’s telegraphs to Dix:

At left a messenger hands an envelope to Stanton, announcing, “Mr. Secretary! here is a dispatch. We have captured one prisoner and one gun; a great Victory.” Elated over this minuscule achievement, Stanton exclaims “Ah well! Telegraph to General Dix [Union general John A. Dix] immediately.”