As scarcity increased in the South, the Richmond Daily Dispatch continually shared ideas for substitute products and ways to stretch the food that was available. 150 years ago today it published a bit of persevering humor: the fastings and sacrifices of Lent were becoming a year-long fact of life in the South’s capital.

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch February 20, 1864:

Dry Eatings.

In what way the day of Lent is to be kept this year in order to distinguish it from other seasons of the year, might puzzle a Carthusian monk. Under the dietetic laws of that order, the brethren were not to eat meat at any time, and during Lent they were prohibited the use of eggs, milk, butter and cheese. Dry bread with water was their Lenten fare, but dry bread and water have been the daily food of some salaried officials in this city all the year round. This is not the result of any scarcity of the fruits of the earth, but of the disordered currency, for there is no article of food or clothing which cannot be purchased at pretty much old prices for gold. But whatever the cause, the “Dry Eatings” are an established institution, and Lent, instead of forty, lasts three hundred and sixty-five days.

As misery loves company, it may be consolatory to those who are keeping Lent by compulsion to recall the austerities of the table which some ascetic persons have voluntarily endured. We find a number of edifying instances collected to our hand in a chapter before us on the “Diet of Saints.” It is recorded of St. Macarius that for years together he lived only on raw herbs and pulse; that during three consecutive years he existed on four or five ounces of bread daily, and that he consumed but one small measure of oil in a twelve month. At Lent he distinguished himself by eating nothing at all on the week days, and a few raw cabbage leaves on Sunday. St. Macarius ought to have lived in Richmond. He would have learned a lesson of humility. Cabbage heads there are in abundance, but cabbage leaves on Sunday or any other day is a piece of extravagant sensuality which neither saints nor sinners, in any great number, indulge. … [more saintly examples]

Winwaloe, a Welch saint, kept his monks at starving point all the week, refreshing them on Sundays by microscopic rations of hard cheese and shell fish. He lived himself on barley bread, strewn with ashes, and when Lent arrived the quantity of ashes was doubled.

Innumerable examples might be multiplied, of a similar character, to stimulate our abstemious Richmonders in that Lenten austerity of life which is preached to them from the butcher and vegetable stalls of the city markets. Not many of them are likely to come to such short commons as “Diet of Saints,” and it is some consolation to reflect that the majority have not yet felt the war. We have heard of no case of starvation as yet, which we attribute to the fact that those who have plenty eat enough for themselves and all the rest of the community.

“there is no article of food or clothing which cannot be purchased at pretty much old prices for gold.” As mentioned yesterday the law passed by the CSA on February 17, 1864 had a temporary effect on inflation by controlling the money supply and making the currency a little less “disordered” apparently. At Civil War Richmond you can view an approximate chart that compares the purchasing power of Confederate notes with a dollar’s worth of gold. In March 1864 the ratio was $26 Confederate to $1 in gold. There was a dip in April, and then the currency relentlessly depreciated for the rest of the war. The poor “salaried officials” who were undoubtedly getting paid in paper.

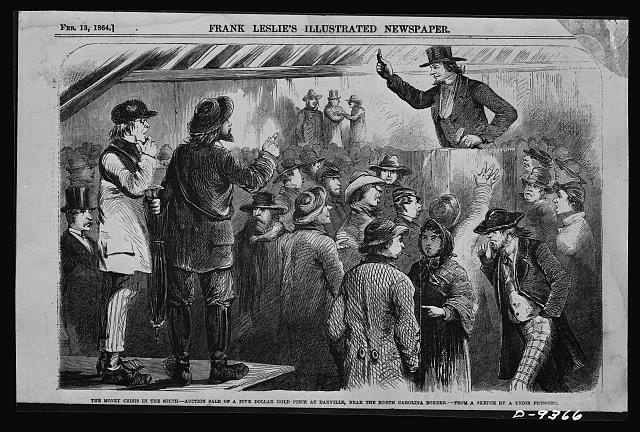

The money crisis in the South – auction sale of a five dollar gold piece at Danville near the N. Carolina border

The image above was from a sketch by a Union prisoner and was published in the February 13, 1864 issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper.