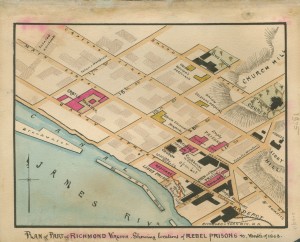

150 years ago this morning jailers at Richmond’s Libby Prison found out they had lost something – 109 Union officer prisoners who escaped during the night through a tunnel they had dug. Although Colonel Thomas E. Rose was the leader of the escape (see Wikipedia link below), a newspaper up here in the North gave the lead billing to Colonel Abel Delos Streight, leader of a mostly unsuccessful raid in northern Alabama in the spring of 1863. His force was captured by General Forrest’s troops. Colonel Streight was sent to Libby. Apparently a Richmond paper also focused on Streight because he was “charged with having raised a negro regiment.”

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch February 11, 1864:

Important escape of Yankee prisoners

–Over Fifty Feet of Ground Tunnelled.–The most important escape of Federal prisoners which has occurred during the war took place at the Libby prison sometime during last Tuesday night. Of the eleven hundred Yankee officers confined therein, one hundred and nine [f]ailed to answer to their names at roll call yesterday morning. Embraced in this number were 11 Colonels, 7 Majors, 32 Captains, and 59 Lieutenants. The following is a list of the Colonels and Majors:

Col A D Streight, 51st Indiana regiment, a notorious character captured in Tennessee by Gen Forrest, and charged with having raised a negro regiment.

Col W. G Ely, 18th Connecticut.

Col J F Boyd, 20th army corps.

Col H C Hobart, 21st Wisconsin.

Col W P Kendrick, 3d West Tenn cav.

Col W B McCreary, 21st Michigan.

Col Thos E Rose, 77th Pa.

Col J P Spofford, 97th N Y.

Col C W Tilden, 16th Maine.

Col T S West, 24th Wisconsin.

Col D Miles, 19th Pa.

Major J P Collins, 29th Ind.

Major G W Fitzsimmons, 37th Ind.

Major J H Hooper, 15th Miss.

Major B B Macdonald, 100th Ohio.

Major A Von Mitzel, 74th Pa.

Major J N Walker, 73d Ind.

Major J A Henry, 5th Ohio.

Immediately on discovering the absence of these prisoners some excitement was created among the Confederate officers in charge of the prison, and in a short time every means was adopted to ascertain the manner of their escape. At first Major Turner was inclined to the opinion that the sentinels on duty had been bribed to pass them out, and this impression was strengthened by the assertion of the Yankees remaining behind that the work had been accomplished through means of heavy fees, which had been paid a Confederate officer in the building, and his influence over the guard in their behalf. On learning this the order was given to place the guard under arrest and commit them to Castle Thunder. Not feeling satisfied about the matter, the Major and Lt. Latouche determined to leave no stone unturned to ferret out the mystery, and thereupon proceeded to institute a search in every direction for further information. After a fruitless examination of every part of the building where it was thought possible for a man to escape, they were about abandoning further investigation, when the idea struck them that some clue might be obtained by going into the lot on the opposite side of the street, when a large hole was soon discovered in the corner of one of the stalls of a shed which had been used as a stable, and on a line with the street running between it and the Libby prison.–This discovery fully satisfied them that they had found out the means by which the escape had been made, and their next step was to trace out the spot where the tunnelling was commenced. Some few yards from the eastern end of the building, in the basement it was found that a large piece of granite, about three feet by two, had been removed from the foundation and a tunnel extending fifty-nine feet across the street, eastward, into a vacant lot formerly known as Carr’s warehouse, out through. This tunnel was about seven feet from the surface of the street, and from two and a half to three feet square. The lot in which the excavation emptied is several feet below the street, and the fleecing prisoners when they emerged from the tunnel found themselves on level ground. Running on Cary street is a brick building, through the centre of which is a large arch, with a wooden gate to permit egress and ingress to and from the lot. By this route they got into Canal street, and keeping close to the caves of the building they succeeded in eluding the vigilance of the sentinels on duty. The prisoners are confined in the second story of the Libby prison, and the first and basement stories had to be attained before the mouth of the tunnel could be reached. From the first floor leading to the basement there was formerly a stairway, but since the building has been in use as a prison the aperture at the head of the steps has been closed with very heavy planks.

By some means the prisoners would cut through both these floors when they wished to gain the cellar, and after they had passed down would close up the holes with the planks which had been taken out so neatly that it could not be discovered. The cellar covers the whole area of the building and is only used as a place for storing away meal, &c., for the use of the prison. It being very large only the front part was required, and therefore the back part of it, which is considerably below Cary street, is scarcely ever visited. The dirt which accumulated as the work progressed was spread about this part of the basement and then covered over with a large quantity of straw which has been deposited therein. It is not known how long the operatives in this stupendous undertaking have been engaged; but, when the limited facilities which they possessed is taken into consideration, there can be no doubt that months have elapsed since the work was first begun. The whole thing was skillfully managed and bears the impress of master minds and indomitable perseverance.

Sometime since a Yankee Captain was found in the cellar, and on being taken before Major Turner, all smeared up with meal, he gave as his excuse for being there that he did not get enough to eat and was looking for something to make bread with. This was doubtless a falsehood, and his only business was to assist in the work which they had in hand.

There seems to be no doubt that further escape through this avenue was contemplated, and the earnestness with which the prisoners who remained behind tried to throw the blame upon the guard was only done to prevent further inquiry into the matter, and thereby leave the tunnel open for others to pass through. Probably one more night might have emptied the prison of the whole number confined therein.

Yesterday workmen were engaged in stopping up the passage which had been made from the prison, and it may now safely be relied on that no other prisoners will ever take their departure from the Libby against the knowledge and consent of the officers in charge.

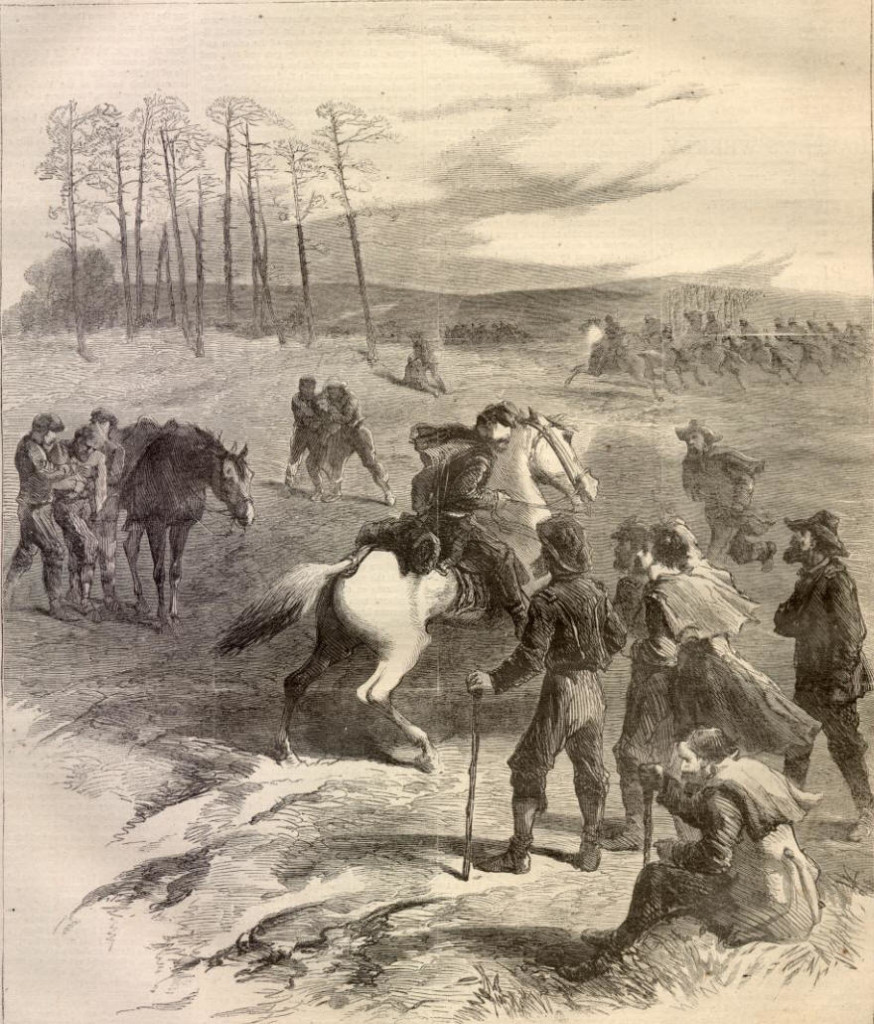

As soon as the facts of the escape became fully known, orders were received by Col. Brown, commanding the cavalry battalion for local defence, that a detachment of his force should immediately scour the surrounding country in pursuit of them, and accordingly twenty-five men from each company soon started off for that purpose. Four of the prisoners who succeeded in getting out were, late in the afternoon, recaptured and brought back. They had gotten about 22 miles from the city before they were overtaken. It is hardly probable, from the steps which have been taken to prevent it, that many of them will succeed in reaching the Yankee lines.

From a Seneca County, New York newspaper in February 1864:

Col. Streight and one hundred and nine Union officers recently escaped from Libby Prison, Richmond. The most of them have safely reached our lines.

Well, just barely. According to Wikipedia only fifty-nine escapees made it to Union lines., but

To judge the success of the Libby Prison escape solely by the number of men who crossed Federal lines would be a mistake. Richmond was deeply affected by the break, and Libby Prison itself was thrown into chaos, much to the satisfaction and raised morale of the remaining prisoners.

The image of the “escaped refugees” was published in the March 5, 1864 issue of Harper’s Weekly at Son of the South.

You can view Colonel Streight’s grave at Civil War Album, which also points out a couple difficulties with the 1863 raid right from the outset: the raiders were mounted infantrymen with no cavalry training, and they were riding on those cantankerous mules.