150 years ago an editorial in the Confederacy argued that the new nation would be better off if its economy were more self-sufficient, more like the Yankee economy, in fact. It is interesting that the piece harkened back to Jamestown’s John Smith making “gentlemen” work for their sustenance. And the newspaper claimed that the South had already gained its independence by the sword.

This editorial resonates with me today. I think free markets and free trade are mostly beneficial, but are there any limits? Could war be a limit?? If we got all our food from Canada, what would happen if the U.S. and Canada went to war?

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch February 4, 1864:

The Guarantee of the future.

Capt. John Smith, the most wonderful combination of chivalry and common sense that history records, complained bitterly of one of his direst afflictions in America, and petitioned most urgently the English authorities for relief. It was not the savage warriors of the Western wilds who thus vexed his valorous soul and made him almost despair of the success of his great enterprise. The very sight of his grim face on the field of battle was enough to scare a whole tribe of red men to the thickest wilds of their forests. It was not pestilence nor famine that made him quail, and mourn, and rage. No! It was gentlemen. It was men who were too proud and too lazy to work, who though labor beneath their dignity, who consumed the fruits of the earth faster than John Smith could collect them, and who, having nothing else to do, were continually wrangling with each other and with him, and wasting in self-indulgence and selfish quarrels the little energy of their natures. Send me over, said Smith imploringly to the London Company, a hundred carpenters, blacksmiths, diggers up of trees’ roots, instead of these “gentlemen.”

It was not that “the gentlemen,” in the true acceptation of that term, was distasteful to one who was himself the first gentleman of that age, and the very flower and mirror of the world’s chivalry. It was not that a radical and levelling spirit marred the fair proportions of his great understanding and character. The only radicalism that he favored was, in his own words, the “digging up of the tree’s roots;” the only “levelling,” that which pulls down and marches over the obstacles to the cultivation of the soil and the establishment of civilization. It was an often quoted maxim with him that he who would not work, neither should he eat, and that kind of gentlemen he wanted not in America. He held that labor is not beneath the dignity of a true gentleman, and the loafers and vagabonds who looked upon it in that light as the worst enemies of the colony of Virginia. Peter the Great seems to have had as keen an appreciation as Capt. Smith of the value of mechanical labor. He perfected himself in various trades, and endeavored to diffuse the knowledge of them among his countrymen. It is impossible that any nation should attain prosperity, or preserve it when attained, where the development of manufacturing, agricultural, or mechanical industry is held in light esteem.

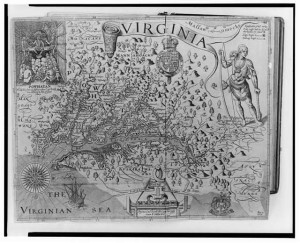

Among the most cunning devices of Yankee legislation to render the South forever a helpless tributary, was that system of policy by which the North managed to monopolize manufactures, and cajoled the South into the belief that the cultivation of the soil was the only species of labor which would remunerate her enterprise. If the South had diversified her industry, if she had built up manufactures and commerce, and encouraged mechanical industry in every form, how different would be her condition now! What would she care for blockading squadrons? What would she have seen of those enormous prices which are now paid for every production of mechanical labor? She would be a world in herself; she would herself produce every article of wearing apparel, of household and agricultural use, build her own iron-clads and rams, and construct all her own weapons of war as well as peace. But, unfortunately, the energy of the South was devoted exclusively to agriculture and polities. What might she be now if the vast capacity which so long guided the affairs of the United States, and raised it, under a long succession of Southern Presidents and statesmen, to an amazing pitch of power and glory, had been devoted to home affairs and the development of her own industrial resources?

Let us trust that, in severing the last link of our connection with the United States, we are entering a career not only of nominal but of real independence. We must not be dependent hereafter upon. New England or Old England for any production of human hands that human necessities require. We must not dream of giving even our carrying trade to foreign powers. There was a time when, in our anxiety for friends abroad we were proffering our future commerce to England or France, but they have been deaf to all those blandishments. This, which some among us have considered an evil for tune, may prove the best of all fortunes.–Certainly it will if it leads us to depend upon ourselves. We shall have no friends to reward, for the excellent reason that we have no friends. We have been left alone to struggle with a colossal foe, and alone, we should reap the fruits of that struggle. We have the greatest natural facilities for becoming a great commercial and manufacturing people, as well as mechanical labor. We must learn to exalt and dignify labor, and make it honorable in every branch of human enterprise. We must encourage none of that genteel loafing and laziness which impeded Captain John Smith in the foundation of the Virginia colony. We should not import the degraded manufacturing labor of Europe, but raise up artisans among our own people, manufacture our own clothing, furniture, and agricultural implements, build our own ships, and man them with our own seamen. Congress and the State Legislatures should encourage Mechanics’ Institutes, like that which was established in Richmond before the war and similar associations in England, which the aristocracy of that country have wisely assisted by their counsels and means, and cheered by their personal presence and co-operation at the annual celebrations.–We shall never again have such a war as this on our hands if we learn to provide by our own labor for our own wants. The sword has achieved our independence, but it is only the industry’ of the artisan and the agriculturist which can make it secure.